Anne Wright (1929-2023)

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 12,

December 2023

By Raza Kazmi

The passing of Anne Wright marks the end of an era not just in India's conservation history, but also in the larger cultural history of pre and post-independence India. Nora Anne Layard was born in 1929. Her father, Austen Havelock Layard, was an I.C.S. officer who had postings ranging from the remote 'jungli' stations of the erstwhile Central Provinces to a palatial bungalow on Rajpur Road in Delhi, while he served six long years as the city's Deputy Commissioner. Anne, the eldest daughter of her doting father, accompanied him everywhere; she went from being a kid who would follow tiger pugmarks in Melghat or watch leopards resting on the parapets of the Gawilgarh Fort, to a young teenager interacting with the family of the Viceroy in Delhi.

Anne Wright photographed at the Sanctuary Wildlife Service Awards in 2013 when she was awarded the Lifetime Service Award for her immense contributions to conservation. Photo: Yogesh Patel/Sanctuary PhotoLibrary.

However, wherever Anne was, she knew her heart lay in the forests of her childhood, the great sal forests of the Central Indian highlands, with its myriad of birds and animals. Fortunately, she found love and companionship in a young British man, the son of an Indian Police Commissioner, who, much like her, loved India and its great outdoors, and had chosen for it to be his forever home too. Anne Layard married Robert Hamilton Wright – 'Bob' to her and everyone else who knew him – on her 21st birthday, and they set up home in Calcutta, where Bob had a senior managerial position in the British conglomerate Andrew Yule and Co. Ltd. While the forests of her childhood were now a long way away, to Anne's delight she soon found out about another great sal forest not too far from Calcutta, a forest pulsating with rich wildlife and home to many Adivasi communities much like the Gonds, Baigas, and Korkus of the Central Indian Highlands. The forests of Palamau beckoned.

Anne and Bob first visited Palamau, situated in north-western Chota Nagpur of what was then Bihar, around 1950, and fell hopelessly in love with this swathe of green. Thereafter, they visited Palamau frequently, often accompanied by friends. In those days, as was the norm, most of their friends liked doing a bit of hunting, and Palamau had become a favourite hunting ground among Calcutta-based social hunters. Anne used these excursions to get to know Palamau, and over the years formed an intimate bond with the forests of the north Koel river valley. Anne also became a mother and much like a tigress introducing her cubs to her favourite haunts, she immediately introduced her babies, Rupert and Belinda, to her favourite wilderness. Little Belinda was only six weeks old when Anne first took her, in the sweltering heat of April 1953, to the jungles of Palamau.

Wild orphans from these forests would often find refuge in the family's home in Calcutta, be it the orphaned tiger cub named 'Palamau' or a leopard cub named 'Cheetla' (who would go on to become famous when he found a new home at Billy Arjan Singh's farm near Dudhwa, and a new name – Prince). Aided by the company of well-known conservationist and naturalist E.P. Gee, Anne also began familiarising herself with the principles of wildlife conservation. However, it was the year 1967 that finally transformed her life from that of a wildlife lover into a dedicated wildlife conservationist.

"We have been visiting the beautiful jungles of Palamau for the last fifteen years... For two consecutive years the monsoon rains have failed in the area with the resultant loss of crops – a grim tragedy for the villagers who now face starvation.....On a visit in January of this year it was already clear that the shortage of water due to the unprecedented drought was going to affect the wild animals very seriously," she wrote in 1967. The drought Anne was talking about was the Great Bihar Famine of 1967, and Palamau emerged as one of its epicentres. Anne had already predicted the dire situation and had written to WWF (which had not yet come to India) requesting funds to help deal with the oncoming calamity. WWF did not have emergency funds to spare, but they circulated Anne's letter, and the International Society for the Protection of Animals wrote to inform her that they, along with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, were donating £500 to begin her relief work for Palamau's wildlife. Simultaneously, she was able to raise funds from the Animal Welfare Board in Madras, and some other donors who provided emergency donations for relief work. Bob's firm, Andrew Yule & Company, financed a separate scheme to aid the villagers.

Anne Wright in her pony trap at Chikli Koti in Chikalda, June 1939. Photo: Wright Family Collection.

Anne and Bob, and some executives from Bob's Calcutta office and a doctor, Dr. D.N. Biswas, formed an effective volunteer group that provided yeoman service, using the funds they had raised, to both man and animal. In that scorching summer of 1967, Anne and her team camped at a spartan forest rest house named Kumandih (now lost) deep inside Palamau's forests for weeks at a time. She ensured daily deliveries of water to 16 remote forest villages whose Adivasi inhabitants – Oraon, Parhaiya, Birjiya, Kharwar, Kisan, Korwa, Bhogtahs, and Cheros – and cattle had been left with absolutely no water. She used to recall how during a critical six-week period she and her co-volunteers, using jeeps and trailers, hauled thousands of gallons of water over rough jungle tracks to these remote villages. Medical and food camps were also organised.

At the same time, Anne and her team created small waterholes in the forest nullahs for the wildlife and used oil drums cut in half as water troughs. They filled these with water every day to ensure that the animals did not stray into the villages and get killed, and they worked with the forest department to control the outbreak of forest fires. This experience changed Anne forever. Forged in those scorched forests of Palamau, was born a conservationist who would subsequently become a pioneer and trailblazer in the true sense of the word.

Palamau thus became the karmabhoomi for Anne, the conservationist. Over the years, she had cultivated friendships with a lot of committed forest officers of undivided Bihar, among whom S.P. Shahi was the most prominent. By the end of 1967, while her fortitude and toughness had earned her the respect of the forest bureaucracy, her kindness had touched the local communities, many of whom had relied on the food, water and medicines provided by Anne's team during the famine. The experiences of 1967 also made Anne realise that Palamau could not be protected solely through individual efforts and that it would need an institutional support system both within and outside the government to make meaningful long-term changes. In those days, funds were severely lacking for the forest department, with almost nothing set aside for the management and protection of wildlife. Anne started working on both fronts. She worked tirelessly in convincing politicians of the importance of Palamau, lobbying for it at the Union government level, and ensuring that when WWF came to India (once again, largely owing to her efforts), Palamau was among the first forests that the organisation focused on. Similarly, she began helping the forest department with capacity building and technical expertise so that the case for protecting Palamau could be made from within the system by the forest bureaucracy.

Anne brought top ecologists and experts from IUCN and WWF, such as Dr. Collin Holloway, to Palamau and organised technical conferences and training camps for the officers and staff to acquaint them with the latest wildlife management techniques. She even helped chalk out a wildlife management plan for the region. Anne would sit with Dr. Holloway, S.P. Shahi, and other IFS officers such as R.P. Singh and J.P. Sinha for long hours, and eventually they came up with the first comprehensive wildlife management plan in India's history for a 'Game Sanctuary', as wildlife-rich forests were then called. Game Sanctuaries were a precursor to wildlife sanctuaries and national parks that came into being post-1972, when The Wild Life (Protection) Act was enacted. Anne also helped the department create the necessary infrastructure, and ensured that the fund-starved offices of the Palamau Forest Division got funding from non-governmental sources and donors, the biggest of which was WWF, where she had considerable influence.

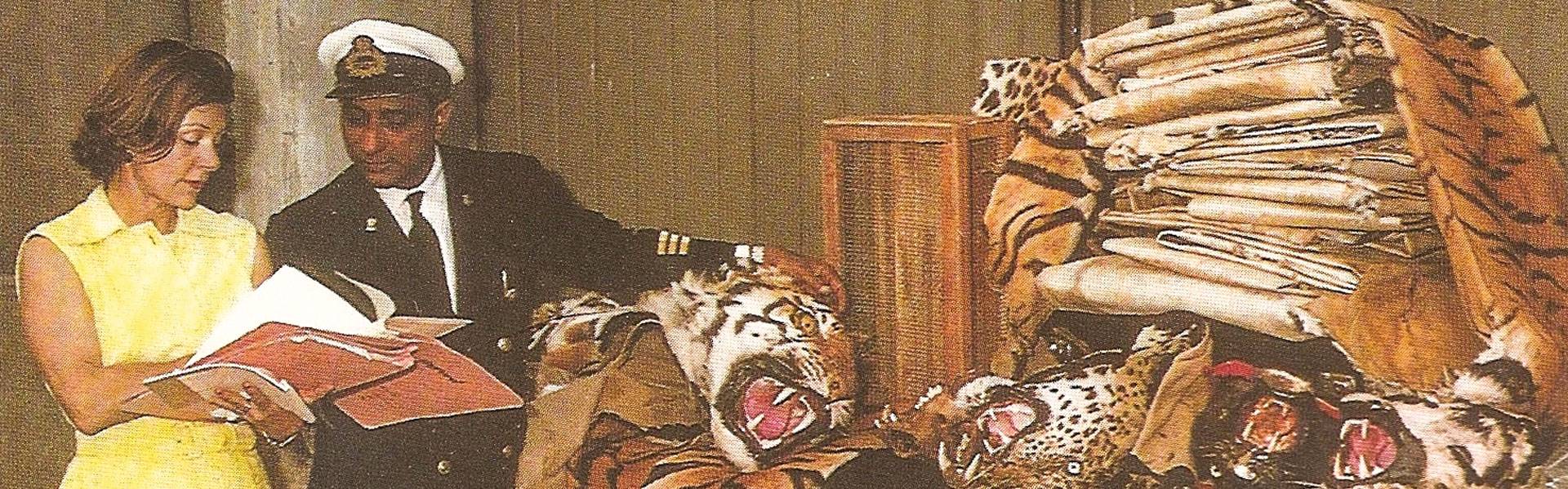

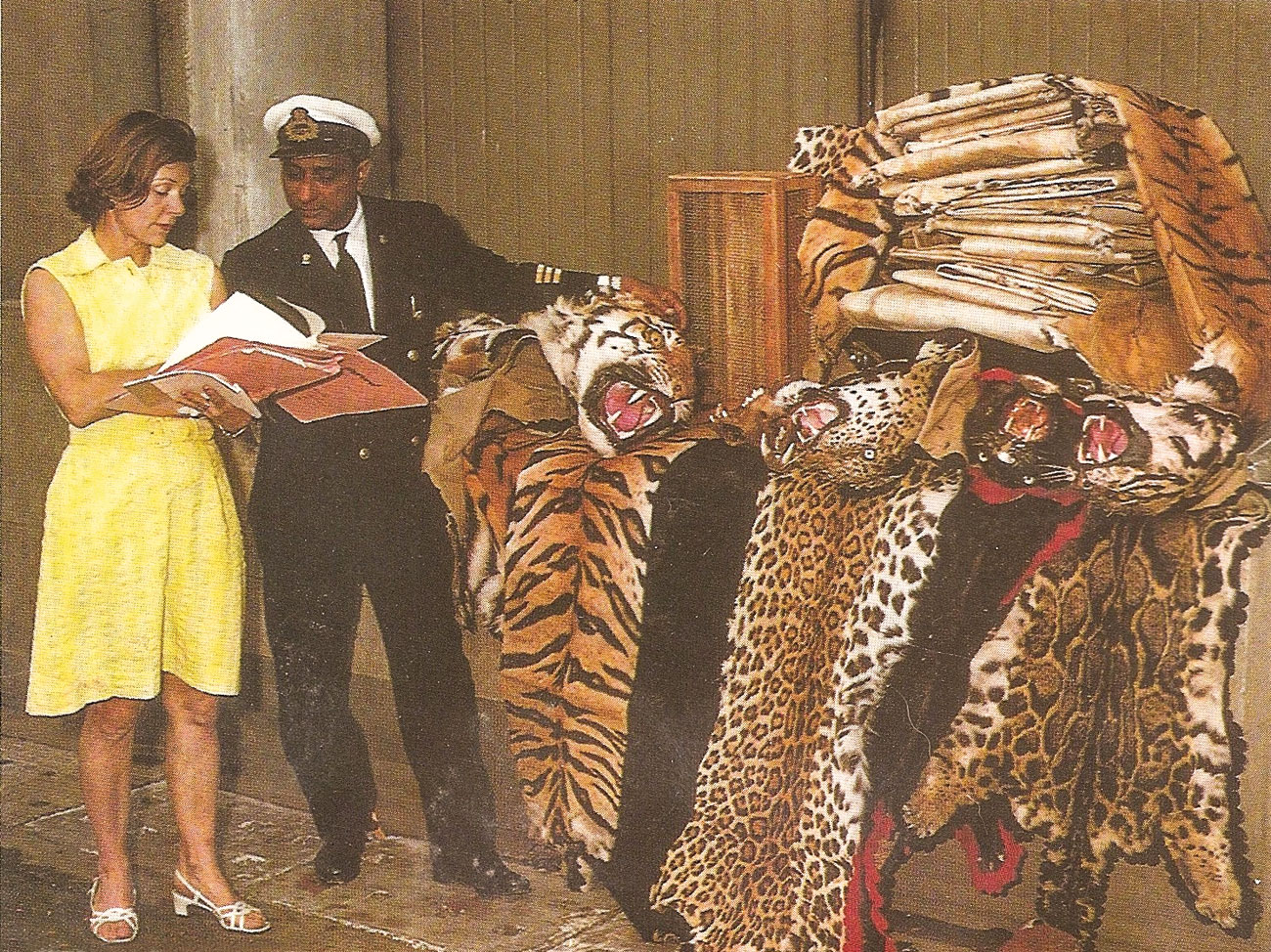

Anne passed on information to the Customs Department, which seized these skins at DumDum Airport, Calcutta, 1972. Photo: Wright Family Collection.

By now Anne had also expanded her work beyond Palamau on a much larger scale, including working on policy issues to save India's imperiled wildlife. She played a critical role in bringing WWF to India in 1969 and was a Founder Trustee. In the same year she was instrumental in organising the prestigious IUCN General Assembly in Delhi, which focussed on the decline of India's tigers and was a watershed event in India's conservation history. However, one of the defining moments of Anne's life as a conservationist came in 1970. While she had been witnessing a severe decline in tigers and other big cats, and was also in conversation about this with some remarkable forest officers such as Kailash Sankhala and S.R. Choudhury, who had been studying the fall in tiger numbers, Anne began her own investigation into the matter. She eventually found out that most of these vanishing big cats ended up in her own city – Calcutta. Through a series of undercover operations, where she posed as an "'innocent tourist'... with the help of a wig, beads and a pseudo-Texan drawl", she discovered that a rampant skin trade in Calcutta was driving the wholesale slaughter of big cats across India.

"Some weeks ago a friend and I went on an expedition to investigate and landed up in a Calcutta back street in search of the place where the illegally shot skins come from... Skins have been my private nightmare, and the shops in Calcutta, where bleached fangs and the glimpse of gold and stripes on shelves make one’s heart sicken. “Yes, Madam, we have rare Clouded Leopard, baby tigers cheaper, see this black leopard – very rare.... one of Calcutta’s big dealers… had been doing Rs. 1 lakh worth of business in tiger and leopard skins a month... He promised a supply of between 20 and 50 fresh tiger skins a month and, to ‘encourage’ us, showed us the uncured skin of a tiger said to have come recently from the Sundarbans. Brought in last week, he said...down a narrow lane...we were...escorted...to a godown where, piled waist high, was the largest collection of fresh leopard skins I had ever seen. Twenty-five uncured leopard skins, two Clouded Leopard skins, and one tiger; gruesome tufts of hair could be seen partly hidden by sacking on the surrounding shelves. Where had this incredible number of animals been killed? The answers were evasive. Bihar, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, U.P. – all over India, they said. They promised a supply of over 200 fresh leopard skins a month if we would only give the order. This explains the sudden rapid disappearance of the leopard from our jungles. The reason for its rarity and the possibility of its extinction are very clear," Anne wrote in 1970 in an explosive article for the Calcutta-based newspaper The Statesman.

The article caused an uproar in Parliament. Anne's story was then republished in The New York Times. The ensuing global storm made the highest offices in India and the West sit up and take notice. It isn't an exaggeration to say that her article and the ensuing outrage it caused, along with the damning photographs on the scale of tiger hunting for the skin trade, convinced Indira Gandhi to ban tiger hunting in the very same year (1970)! That was the power of Anne's pen.

And it didn't stop there. The global outcry in the aftermath of her article in The New York Times led to an outpouring of support for tiger conservation in India in terms of funds, resources, and expertise. It became a catalyst in the revival of the Indian Board for Wildlife, the creation of the Tiger Task Force, The Wild Life (Protection) Act, and the tiger being made the National Animal of India – all in 1972 – and eventually culminated in the launch of Project Tiger on April 1, 1973.

Anne was the only woman member on the government's Tiger Task Force. Their main responsibility was to work out an effective plan for tiger conservation management and to carry out a rapid all-India field survey to identify and document a diverse selection of the best tiger habitats for Central funding and protection. Anne spoke vociferously for the inclusion of Palamau and Manas in the scheme. She also gave a strong voice of support to Saroj Raj Choudhury's efforts to include Similipal in Odisha (another state whose forests Anne had known well since the 1960s). Eventually, all three were included among the eight tiger habitats – Bandipur, Corbett, Kanha, Melghat, Manas, Palamau, Ranthambhore and Simlipal – which were selected in the Task Force's six-year ‘Project Tiger’ proposal. A ninth tiger habitat, Sundarban, was added by Indira Gandhi.

Anne with forest officials celebrating the opening of the Dalma Wildlife Sanctuary, December 19, 1976. In 1974, after visiting this critical elephant habitat, Anne wrote a powerful article and put this little-known forest on the map. Over the next two years, through her unrelenting support and push for the Dalma forests, she eventually succeeded in getting it notified as a wildlife sanctuary. Photo: Wright Family Collection.

These were not the only Protected Areas in which Anne played a key role. Without her, Dalma Wildlife Sanctuary would probably not exist. Situated next to the steel city of Jamshedpur, she first visited Dalma soon after WWF-India was launched. In 1974, she wrote a powerful article for the WWF Newsletter titled War Drums Sound on Dalma Hill, and put this little-known forest on the map. She then began working on multiple fronts to protect this critical elephant habitat. She lobbied persistently with the Bihar Forest Department, the Union Government, the Tata Group and the conservation community on the need to protect Dalma, and it was finally notified as a wildlife sanctuary two years later, in December 1976. Anne did the same for the rich and rugged Neora Valley in West Bengal, a home of the red panda, which was saved from drowning under a dam by her tenacious and forceful intervention, and later notified as a national park in 1986. She did the same for Balphakram in Meghalaya, which was notified in 1987 as a national park. And the list goes on.

Anne was also closely involved with another landmark event in India's conservation history – the drafting and enactment of the Wild Life (Protection) Act in 1972, which has been the legal backbone of India's conservation efforts ever since. She was a key member in the drafting of the Act. Anne sourced a copy of the Kenya Wildlife Act through the Kenyan polo team, which was coming to play polo in Calcutta. This, along with the Bombay Animals Act, were the two key legislative influences in the drafting of the final Wild Life (Protection) Act.

During her long years in conservation, Anne worked with people and stakeholders from all walks of life for her conservation goals. She would speak forthrightly in defence of wildlife and their habitats, and confidently make her case. Her steadfastness, honesty and purpose earned her not just their respect but also their friendship. One of many eminent people she befriended was J.R.D. Tata, who she successfully persuaded to change the entire proposed building plan of the Taj Hotel in Calcutta on behalf of the Lesser Whistling Teal, whose flight pattern in and out of the Alipore Zoo would have been upended by the original plan for a high-rise hotel. Anne also became a trusted friend of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. It was perhaps a bond strengthened not just by a common love for nature but also a camaraderie of, as Belinda eloquently says, "two women breaking glass ceilings in what was then a man's world".

Anne even convinced Indira Gandhi, even when the Prime Minister herself was unsure of the idea, to speak with the leaders of Pakistan and Afghanistan during a summit she was due to attend, about protecting the migration route of the Siberian Crane. She also persuaded Dasho Benji Dorji, cousin and advisor to the former King of Bhutan, to save the precious habitat of the endangered Black-necked Crane in the remote Phobjikha valley.

I could write an entire book on Anne and still not do her justice. She leaves behind a huge legacy, both in terms of the incredible breadth and the depth of her work. The breadth implies both temporal and geographic aspects of her work. She played a leading role in the conservation of wildlife in India for more than 50 years. Her active field work spanned from the highlands of Madhya Pradesh to the remote valleys of Meghalaya, from the forests of Chhattisgarh to the mangroves of Sundarban, from the wilds of Odisha to the jungles of Chota Nagpur, and from the Terai forests of Bihar to the rainforests of the Andaman Islands. Moreover, she was doing all this at a time when conservation, especially field conservation, was almost exclusively a male domain. Throughout her younger days, she worked in forests that were hardly visited by other Indian naturalists, and she was often the only spokesperson for the conservation of those forgotten wild landscapes. She also worked on a multitude of species, from tigers to olive ridley turtles in Odisha, from pheasants to small cats in the Northeast, rhinos to elephants, and everything in between.

Similarly, to illustrate the depth of her work, Anne could envision conservation from a micro level (which could, for example, involve working in a forest village or with frontline field staff) and at the same time, she could draw up excellent policy and conservation plans at a macro level. Her work ranged from helping to draw up a management plan for a single forest to framing state-wise or nation-wide policies as she collectively did during her 19 years on the Indian Board for Wild Life (now National Board for Wildlife), and her even longer tenure on the State Wildlife Boards of seven states. To add to this extraordinary resume, she also served for decades on the Cat Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), and the Asian Elephant Specialist Group, and founded The Rhino Foundation of Northeast India, and so on.

Thus, it is no surprise that Anne was awarded The Most Excellent Order of The Golden Ark by Prince Bernhard of The Netherlands in 1979, Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 1983, and the Sanctuary Asia Lifetime Service Award in 2013.

Among the many things I admired about Anne was her ability to forge alliances over a common cause – from forest officers to politicians, businessmen to forest communities, from celebrities and global and national public figures to young school kids, from naturalists to policymakers – she worked with everyone, and had a knack of bringing people together for the cause of conservation. I can think of very few people, perhaps none, in India's conservation history, who worked over such a vast area for such a long period, and on numerous issues with so many people with varying interests, and who achieved such remarkable results. Anne's articles and reports are also an incredible testament of what one individual can achieve through the sheer force of their writing.

Anne filling oil drum halves with water for wild animals in Palamau during the Great Bihar Famine of 1967. Anne was equally at ease in an all male team as she was working alone. Photo: Wright Family Collection.

Wildlife conservation may have defined her life, but there was much more to Anne. In her later life, she returned to her childhood love for horses and became a horse breeder, producing some of India's finest race horses. More than anything else, Anne was an adventurer, a true heir to the spirit of exploration and adventure of the Layards, including perhaps the most famous one of them all – Austen Henry Layard, who re-discovered the lost, ancient cities of Nineveh and Nimrud in Iraq. A younger Anne could be found following the trail of one of India's most notorious man-eating tigers in the rugged remote hills of southern Odisha one day, following the footsteps of some long-lost British explorer or soldier the next, and exploring old forts and ruins inside a forest the following day. She would often tell me how she used to hear fantastical tales of treasures in the forest, and how she was even tempted to go on a few treasure hunts herself.

From the early 1970s onwards, Anne lived at Tollygunge Club in Calcutta, where Bob was the Managing Member until near the end of his life. Anne was at the heart of the vibrant cultural and social milieu of Calcutta for decades, a friend of intellectuals, artists, and the who's who of the City of Joy. She even dabbled in the world of acting, making her debut in Mrinal Sen's critically acclaimed film ‘Mrigayaa’, which starred Mithun Chakraborty. She was a friend of one and all, from Indira Gandhi to S.P. Godrej, Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur to the Nawab of Murshidabad, Mountbatten's daughter Pamela to Queen Camilla's brother Mark Shand, Dr. Sálim Ali to S.P. Shahi, George Schaller to Manglu Baiga, and scores of other special men and women. She herself was one of the most interesting people you could ever meet, a wonderful raconteur, who would tell you incredible stories and recollections of events, people, and life as it was in the years leading up to 1947 and thereafter, that she had been witness to.

She told me how she had attended Mahatma Gandhi's funeral, where she sat for hours with the Mountbatten and Nehru family surrounded by vast crowds, how she landed in a little plane on a grass airstrip in Cooch Behar to be met by elephants as transport to the palace, her adventures following tigers to nearly being torpedoed in the ship she was travelling on during World War II, about the genius of her friend Satyajit Ray to the eccentricities of her governesses, about the great private libraries that she saw in Princely States that exist no more to rediscovering a forgotten battleground of 1857 in Hazaribagh, her time in opulent ballrooms and chateaux of European royalties to tucking a baby Belinda to bed in a godforsaken haunted forest bungalow, of the thatched official bungalows of her childhood to her beloved ponies, of her varied pets from a variety of dogs to a giant squirrel, and her early exploits on horseback in the wilds of Central India. You could talk for days and days, and yet feel that you had barely scratched the surface of her incredible life.

Though Calcutta was their main home, in 1981 Anne and Bob made a second home, which they called 'Kipling Camp', in the forests of Anne's childhood – Kanha. She spent the last three years of her life amidst those forests with her beloved daughter Belinda, who is Anne's finest legacy, truly her mother's daughter both in her incredible contribution to tiger and wildlife conservation in India and her warmth and love as a person.

For me, it's a deeply personal loss of someone who I looked up to as a loving grandmotherly figure. Even though I got to know her late in life, I spent many days talking to her in late 2019 and then on and off in 2020 and 2021, after which I could only meet her a few times owing to COVID restrictions. There are so many wonderful memories. From the time I spent with her in Kanha on Christmas Eve in 2019, singing carols, to the many hours spent going through her old photo albums, and then her excitement one morning at Kipling when she told me how a tiger had walked by her cottage during the night. She was 90 then, but in that moment of child-like joy, she was nine.

Photo: Wright Family Collection.

One of my fondest memories was when I managed to procure a bunch of fascinating old home movies that were shot by her father and subsequently donated to the Bristol Archives in the UK. There is footage of Anne as a young girl with her sister Val and the various places they grew up in, of her mother who tragically died in Kashmir just after Anne's fourteenth birthday, and of Anne's early married years. Neither Anne nor Belinda had seen these films. I had to jump through a few hoops but eventually, the Bristol Archives agreed to share a digitised copy of all the films with me. I took them to Delhi, where Anne had moved to live with Belinda after Bob died in 2005. Then Belinda and I sat with Anne and watched these silent films – their contents spanning nearly two decades from the 1920s to the late 1940s. I still remember the utter joy in Anne's voice when she saw her mother for the first time on film, her many childhood homes, and her ponies and pets. She vividly described all the scenes to us, giggling and smiling, and at times quite tearful. It is one of my dearest memories of Anne, and one that I often go back to when I am missing her, which I do a lot.

Anne was the sweetest, funniest, and cutest old lady I have ever known. Time literally flew by whenever I was in her company as she would regale me with one incredible life story after another, and we could chat for hours on end. Unfortunately, Anne suffered a massive stroke in the summer of 2022. We knew it was only a matter of time before the inevitable happened and I had been preparing myself for it. Yet, when she passed away, it still hit me like a truck. I spent the next few days re-reading her writings, and stories written by others on her life and work, listening to and watching the recordings that I had made of her, and revisiting her old photographs and my photos with her. Belinda told me that Anne's final departure was more beautiful than I could imagine, that she bid farewell to this world in peace at her home in Kanha surrounded by the camp staff, both past and present, friends and local people from nearby forest villages who loved her, Anne's beloved Tara (she is a famous elephant, the protagonist in a book written by writer-adventurer the late Mark Shand, Queen Camilla's brother, who was gifted to the Wrights in 1988) and their two faithful dogs – Holly and Islay. Even the wild denizens of Kanha seem to have paid their salaams. Belinda narrated how, while Anne was being taken on her final journey on the evening of October 4, "there were alarm calls down at the fireline, and the camp was crowded with chital when we returned". Anne was cremated at a beautiful, secluded village cremation site, near Kanha's boundary with a gurgling stream beside it. Owls were hooting into the night, cicadas were singing, millions of stars shone in the clear sky above, fireflies lit up the surrounding foliage, and tall sal trees gave Anne a guard of honour, watching over her as silent sentinels.

Farewell, Anne ma'am. Till we meet again.

Raza Kazmi is a Jharkhand-based conservationist, wildlife historian, researcher and storyteller. He grew up in the lush forests of eastern India and was witness to the trials and tribulations of his father S.E.H. Kazmi’s life as a forest officer as he stood up to insurgency and bureaucratic challenges in Jharkhand (then in Bihar) to resurrect the Palamau Tiger Reserve.