An Indigenous Response To The Climate Emergency In India

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 8,

August 2022

By Rituraj Phukan

COP26’s Gross Inadequacies

In November 2021, at the U.N. Climate Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, I attended a massive rally where Greta Thunberg rebuked world leaders: “They have had decades of blah, blah, blah – and where has that got us?” She declared the conference a “failure” and a “PR exercise” even before the end of the first week of negotiations. Her words were almost prophetic; the conference ended in the woefully inadequate Glasgow Climate Pact, a compromise agreement that has barely kept alive the hope of limiting warming to 1.50C above preindustrial levels.

Climate change and its colossal impact is caused mostly by human action and inaction. Modernisation and development disrupt both ecosystems and the livelihoods of people worldwide. The worst and first hit are Indigenous People and Local Communities (IPLC) that live in untouched natural environments, such as forest dwellers, who are dependent on natural resources around them. Although they bear the brunt of the climate crisis, they do not cause it. They have one of the smallest carbon footprints in the world.

I was witness to the anxiety of the youth and the anger of the affected communities braving the cold November rain, from Kelvingrove Park to George Square on the Global Day of Action for Climate Justice during COP26. IPLC youth, women and elders representing the most affected regions were there, dressed in their traditional finery. And yet, I did not see the representatives of montane, riparian, coastal and inland communities in India – who are at the frontline of the climate crisis – taking part in these demonstrations.

A protester holds an umbrella printed with Greta Thunberg’s strong rebuke at a march held on the Global Day of Action for Climate Justice. Organised by the COP26 Coalition, the day saw hundreds of thousands of people around the world mobilise through diverse action. Photo: Public Domain/Oliver Kornblihtt/Mídia NINJA.

Climate Crisis In India

India is a country of diverse ecosystems, where varied forms of adverse climate events and transformations are taking place. Glacial meltdowns, floods, and the loss of forest cover threaten almost all of the 705 nationally recognised indigenous communities. The consequences of climate change have exacerbated the difficulties faced by vulnerable indigenous populations in many regions, populations that are struggling to make ends meet in their everyday lives. To resolve such a climate crisis, there is a need to map the nature and extent of the climate emergency for the IPLC of the Indian subcontinent. The following are some of the dimensions that emerge from various narratives and scientific studies.

Across the Himalayan region, the indigenous communities that depend on the seasonal flow of water are threatened by accelerated glacial meltdown and by flash floods. The short-term and long-term impacts will affect millions of montane and riparian communities across the Himalayan region. Since a disproportionate section of the population living in India’s highland regions are indigenous people, this means they will be the most affected by the future decline of glacial runoff in terms of the effects on agriculture.

However, world leaders need to act decisively as scenes such as these of a flood affected area in Bihar, taken on August 28, 2008, are becoming increasingly frequent. Photo: Public Domain/Public Resource.org.

But there are numerous indigenous groups that live in the lowland regions of India who will also be affected by changes there. According to the Climate Vulnerability Index released by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, states like Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Odisha, and Bihar are most vulnerable to extreme climate events such as floods, droughts, and cyclones in India. For instance, Odisha was hit by the super cyclone of 1999 that upended the lives of many marginalised communities.

Further, recent environmental changes brought on by climate change especially impact indigenous people because of their close relationships with the land, ocean, and other natural resources. IPLC maintain a symbiotic relationship with their immediate ecosystems, so whatever harms the landscape directly harms the people and vice versa. When changing environmental conditions result in habitat loss, this can offset the balance between humans and important wildlife species. Loss of forest cover, invasive vegetation, and loss of indigenous food sources have caused direct threats to the food security of millions. These issues also trigger human-wildlife conflicts that further disrupt the socioeconomic life of indigenous communities in the country.

Climate change triggers financial crises, disrupts economically productive activity, and displaces marginalised communities. Combating the rising frequency and scale of extreme climate events is socially and economically draining for developing countries such as India. The livelihoods of over 500 million people are endangered by the potential damage climate change will have on agriculture. IPLC settlements are threatened because their housing is most likely to be in areas prone to flooding, and the construction of their housing with natural materials makes them particularly vulnerable to high-wind conditions.

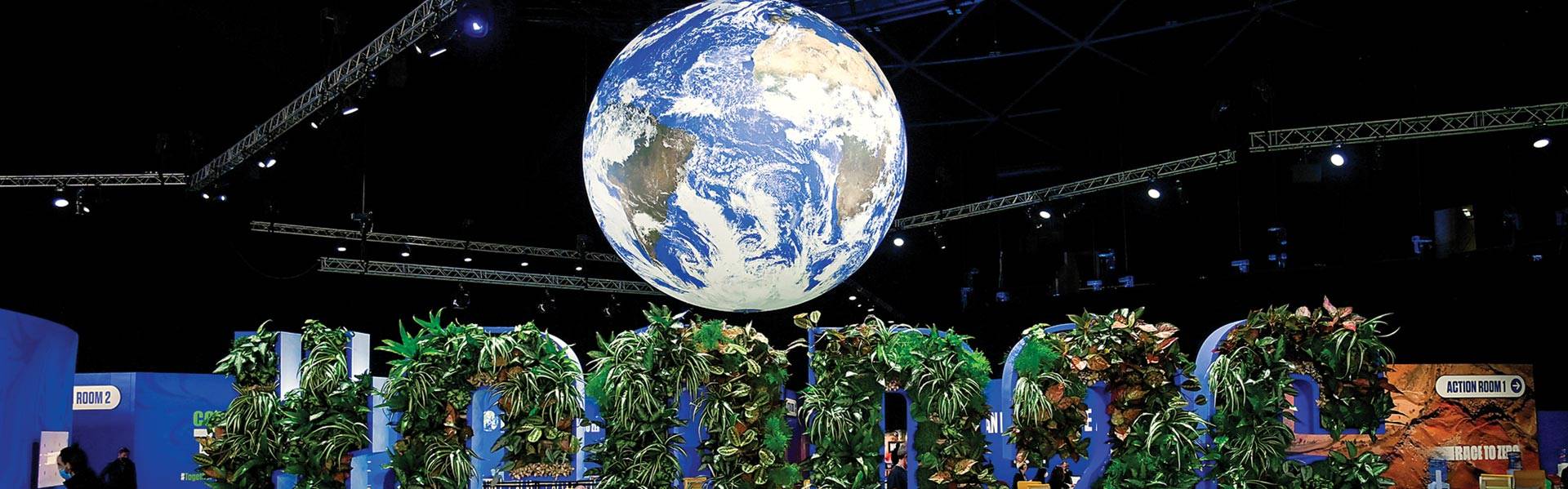

A massive suspended globe spinning at the Hydro, an indoor arena and one of the venues for COP26 in Glasgow. The conference ended in the woefully inadequate Glasgow Climate Pact, a compromise agreement that has barely kept alive the hope of limiting warming to 1.50C above preindustrial levels. Photo: Public Domain/Karwai Tang/ U.K. Government.

Although indigenous people have taken many actions to combat climate change, their role in addressing this problem is underrepresented in public discourse. There are many instances of Indian indigenous groups that have responded to the climate emergency, with or without funds. Jadav “Molai” Payeng, from the indigenous Mising tribe of Assam, grew trees over years on a sandbar of the river, which became a forest that now abounds with rich biodiversity. Responding to the climate emergency and the low streamflow in Ladakh, Sonam Wangchuk, a mechanical engineer from the Leh district, and his team of volunteers initiated the movement of creating artificial glaciers. Although press coverage of environmental issues and stories of climate activists have increased, the message is still not reaching the public. There are specific reasons why support for climate activism is inadequate.

Although indigenous people have taken actions to combat climate change, their role is underrepresented in public discourse. In Ladakh, locals are experimenting with innovative ideas like building ice stupa artificial glaciers. Photo: Rigzen Mingyur.

Offsetting Real Accountability

Since the leaders of developed nations are reluctant to call on their own citizens to give up private jets, large private vehicles, unnecessary travel, or overheated buildings to stem climate change, they turn to schemes in developing nations to “offset” the damage they cause at home. These policies are often paper transactions that change nothing, but sometimes scar developing nations deeply, often in areas that are inhabited by IPLC. Policy interventions should not impose a global ecological morality based on a shell game played by wealthy corporations. Quite often, they are based on confusing methods of carbon accounting that are more likely to baffle the innocent than reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, any actions taken on indigenous lands should be sensitive to cultural variations and local autonomy.

Some of the worst projects imposed on indigenous people have been biofuel projects that supposedly reduce net carbon emissions, at least during the period when crops are grown to be used as fuel. Whether they actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions remains to be seen. But for the people whose lands are taken, these projects are unambiguously harmful; they lead to an increase in monoculture crops and plantations and an associated decline in biodiversity and food security.

Jadav Payeng, ‘The Forest Man of India’, from the Mising tribe in Assam grew trees over years on a sandbar of the river, which became a biodiverse forest. Photo: Sanctuary PhotoLibrary.

Nuance In Solutions

Although global groups have effectively mobilised urban populations, it will take home-grown IPLC representatives to mobilise rural masses. It is crucial that indigenous youth leaders be provided a platform to evolve as communicators of climate action in their respective domains. Above all, indigenous people need to be motivated to solve the challenges posed by climate change. This will require officials to respect the ideas, values, and traditional management systems of IPLC, instead of treating them with suspicion and contempt.

In India, ecological awareness must be spread to improve ecological consciousness so that indigenous people can make informed decisions about their local environment and do what is needed. Government initiatives need to develop the capacity to absorb that knowledge and integrate it into regional plans. Financing needs to enable such communities to develop their own strategies that will support their future. Since poverty is a current constraint on indigenous support for climate programmes, much of the funding needs to serve the dual purpose of poverty alleviation and climate activism. The strength of IPLC lies in their local knowledge, and the imposition of generic or ‘universal’ policy formulations denies their ability to develop more contextual sustainable practices than bureaucrats can from a central office.

The author joined thousands of observers in walking out of the ‘People’s Plenary’ on the final day of the COP26 negotiations in protest against the dilution of the draft agreements. However, he says that the blame on India for imposing’phasing down of coal’ instead of ‘phasing out’ conveniently ignored India’s argument to include all fossil fuels and not just coal. Photo: Shailendra Yashwant.

I joined thousands of Observers in walking out of the ‘People’s Plenary’ on the final day of the COP26 negotiations, aware that the draft agreement was likely to be diluted. However, I did not foresee that India would be blamed for imposing ‘phasing down of coal’ instead of ‘phasing out’ in the Glasgow Pact. The fact that India had argued for inclusion of all fossil fuels, not just coal, was conveniently ignored. Ironically, India was again the 10th best country, with the top three ranks being left vacant, in the 17th edition of the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI 2022) published on the last official day of the negotiations – the only G20 nation to be ranked in the top 10. It will be helpful to have influencers publicly acclaim the climate action by countries in the same manner that their negative decisions are called out. If Greta were to praise India and other countries listed high on the CCPI 2022, she could mobilise millions of new followers in support of positive climate action.

Read more: People’s Response to the Climate Emergency in India.

Rituraj Phukan A member of the IUCN’s Wilderness Specialist Group, as well as other high-level specialist groups, for the South Asia Region, he is also the Assam Coordinator of Sanctuary’s Kids for Tigers, and an associate editor at Igniting Minds.