A Tale Of Two Ferns

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 2,

February 2022

By Soham Kacker

When it rains in the normally hot and dry hills of the Aravalli ranges, it causes an almost overnight efflorescence of a minute but diverse world of plant life. Tiny weeds, herbs, grasses, and mosses seemingly appear by spontaneous generation, softening the edges of the huge granite and sandstone boulders. Special among these ‘ephemerals’, and instantly recognisable, are the only two species of ferns native to the Aravallis – the creeping maidenhair Adiantum caudatum and the ray fern Actiniopteris radiata. While most ferns thrive in cool, wet environments, these xeric (dryland/rock dwelling) species have acquired a suite of evolutionary tricks to survive in the most unlikely habitat.

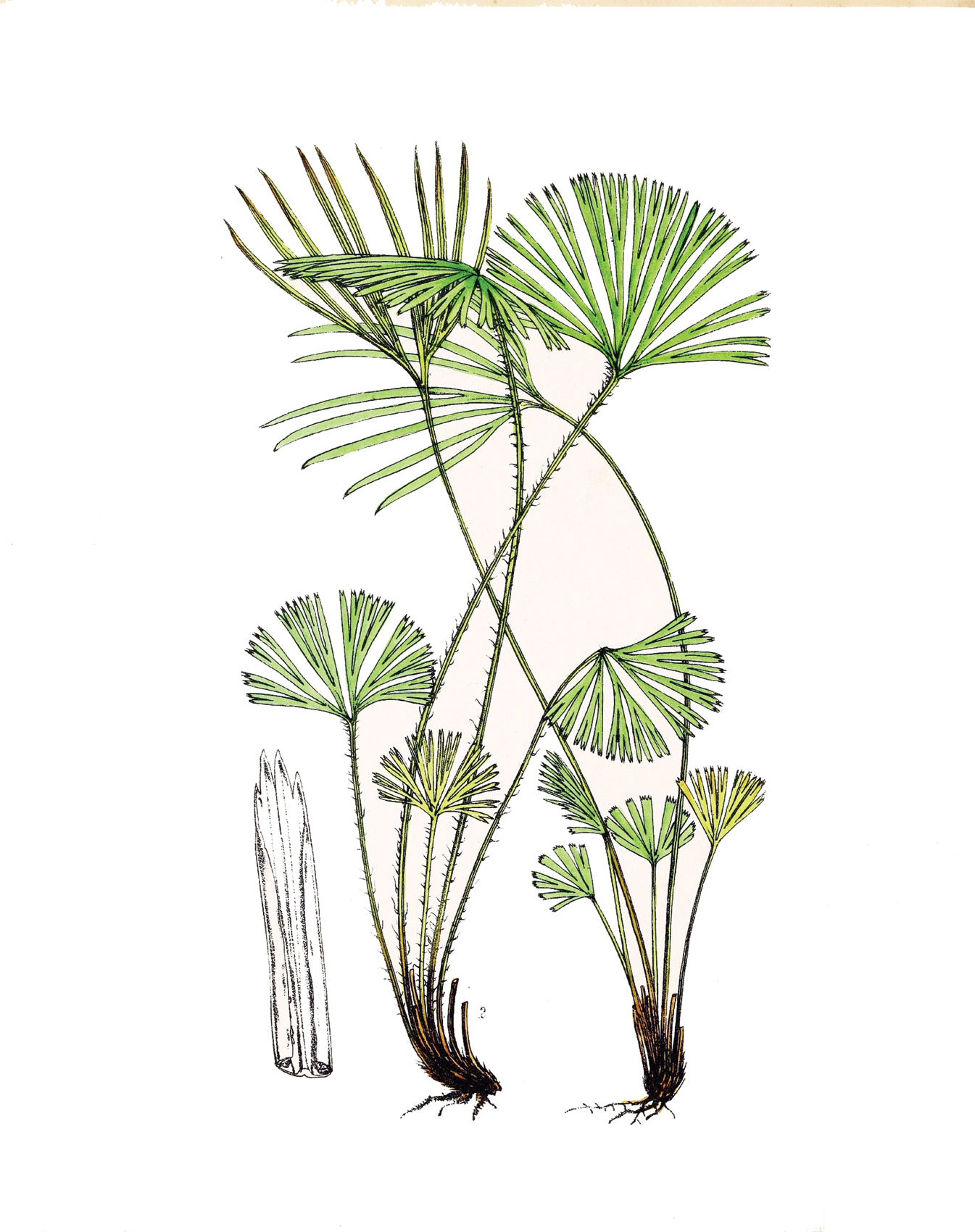

These unique ferns are unlikely to be found in other seasons. As soon as the rains have passed and the soil dries out, they all but disappear – but how? The maidenhair fern shrivels up completely – surviving only as a short underground stem called a rhizome. During seasonal showers, this persisting stem gives rise to new fronds, allowing the fern to miraculously ‘resurrect’. During their short life, the fern’s fertile fronds also produce thousands of spores, which can survive in the environment for months before germinating under favourable conditions. Finally, the maidenhair fern can produce tiny plantlets on specialised extensions at the tips of its fronds (hence its name in Latin – ‘caudatum’ means tail-bearing). By effectively cloning itself, the maidenhair ensures that it maintains a viable population even if its spores do not grow in the next season.

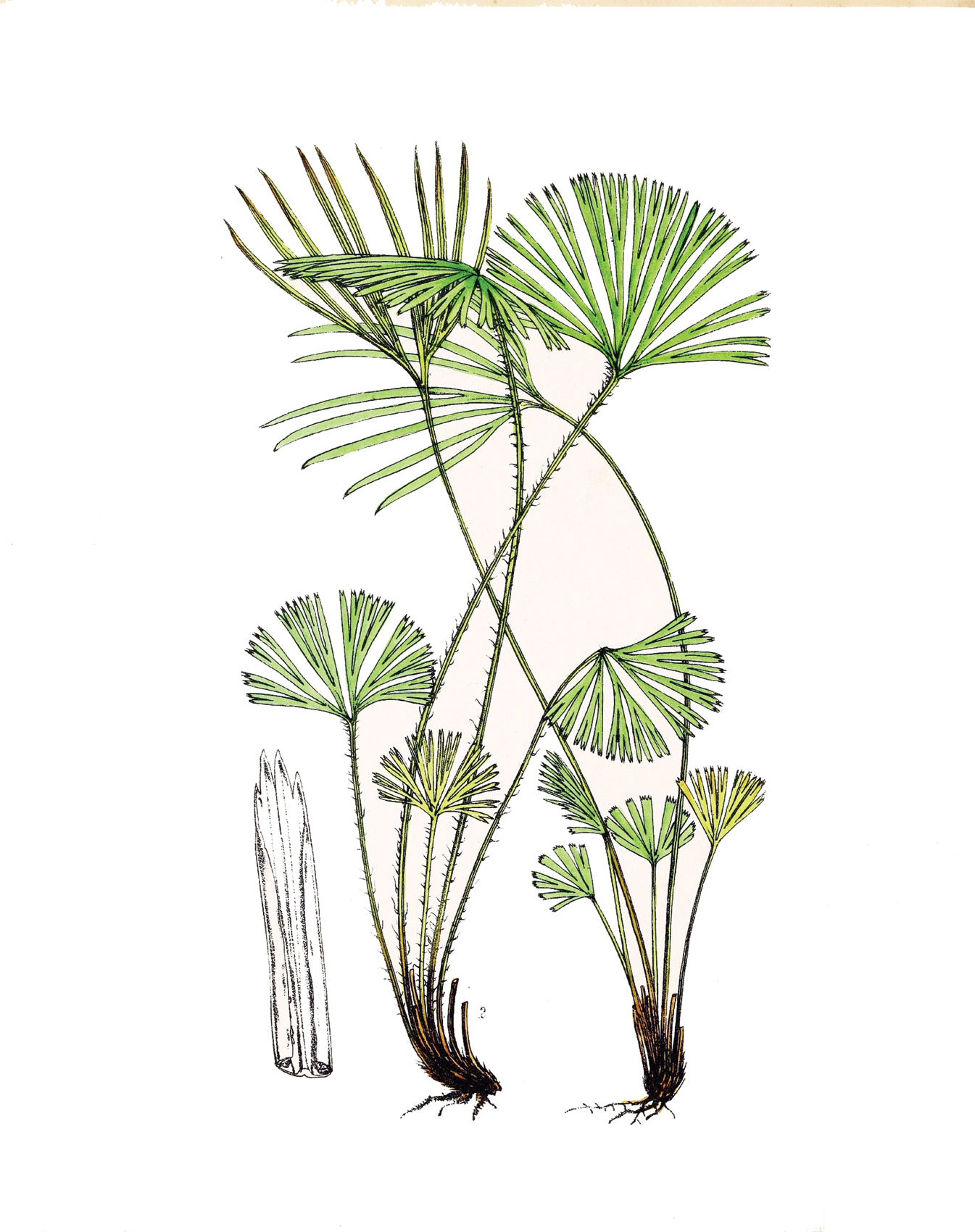

The ray fern along with the maidenhair fern is native to the Aravallis. Both species have adapted in two distinct ways to tide over the dry season. Photo: Public domain/Biodiversity Heritage Library.

On the other hand, the ray fern does something even more unbelievable. Its tiny fan-shaped fronds dry out completely, but remain in this desiccated state until the next rain. Then, these same fronds simply re-hydrate – picking up right where they had left off! It is still not clear how this remarkable recovery is biologically feasible, making these small ferns extremely interesting indeed.

Around five years ago, scientists at the National Botanical Research Institute in Lucknow expressed a fern gene in cotton plants, making them resistant to whitefly infestation. Given that ferns diverged from seed-bearing plants almost 400 million years ago, the successful expression of a gene from a fern into a crop plant so distant on the evolutionary tree of life was an unprecedented proof of concept. Scientists imply that the drought-and-heat-tolerant genes of the maidenhair and ray ferns are also potential candidates for introduction into crop plants. No matter what your opinion is on genetic modification, it is undeniable that genes which allow plants to withstand long periods of adversity and make a full recovery have the potential to radically impact a global agricultural sector facing the challenge of climate change. Aside from being important components of a unique ecosystem, this makes the two little ferns from the Aravalli mountains a prospective source of genetic material that could help ensure livelihoods and food security in a warmer future.

The maidenhair fern shrivels up in the dry season but survives as a short, underground stem called a rhizome. Photo: Public domain/David J. Stang.

Ironically, climate change may pose a threat to the ferns themselves. With longer and more severe dry seasons, their ability to revive is constantly put to the test. While neither species is currently thought to be at risk of extinction, the maidenhair and ray ferns illustrate one of the key arguments in support of conservation – preserving potential biological resources. An assessment of these ferns (and in fact, any organism) must consider not only their intrinsic value as species, but also their intangible value as a genetic resource and their ability to provide essential services to humankind. Take all of this into consideration and these little, ephemeral ferns don’t seem so small anymore.

Note: It is Sanctuary’s position that scientific enquiry has virtually no boundaries. However, Homo sapiens’ flirtation with technologies whose long-term impacts we cannot predict, such as the creation of genetically modified organisms, could pose existential threats that we have no way of controlling.

Soham Kacker is passionate about plants and has apprenticed at the Auroville Botanical Gardens and the Aravalli Biodiversity Park. Based in New Delhi, he is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree in the biological sciences from Ashoka University.