A Fight Of Rhinos

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 4

No. 8,

August 1984

By Samar Singh

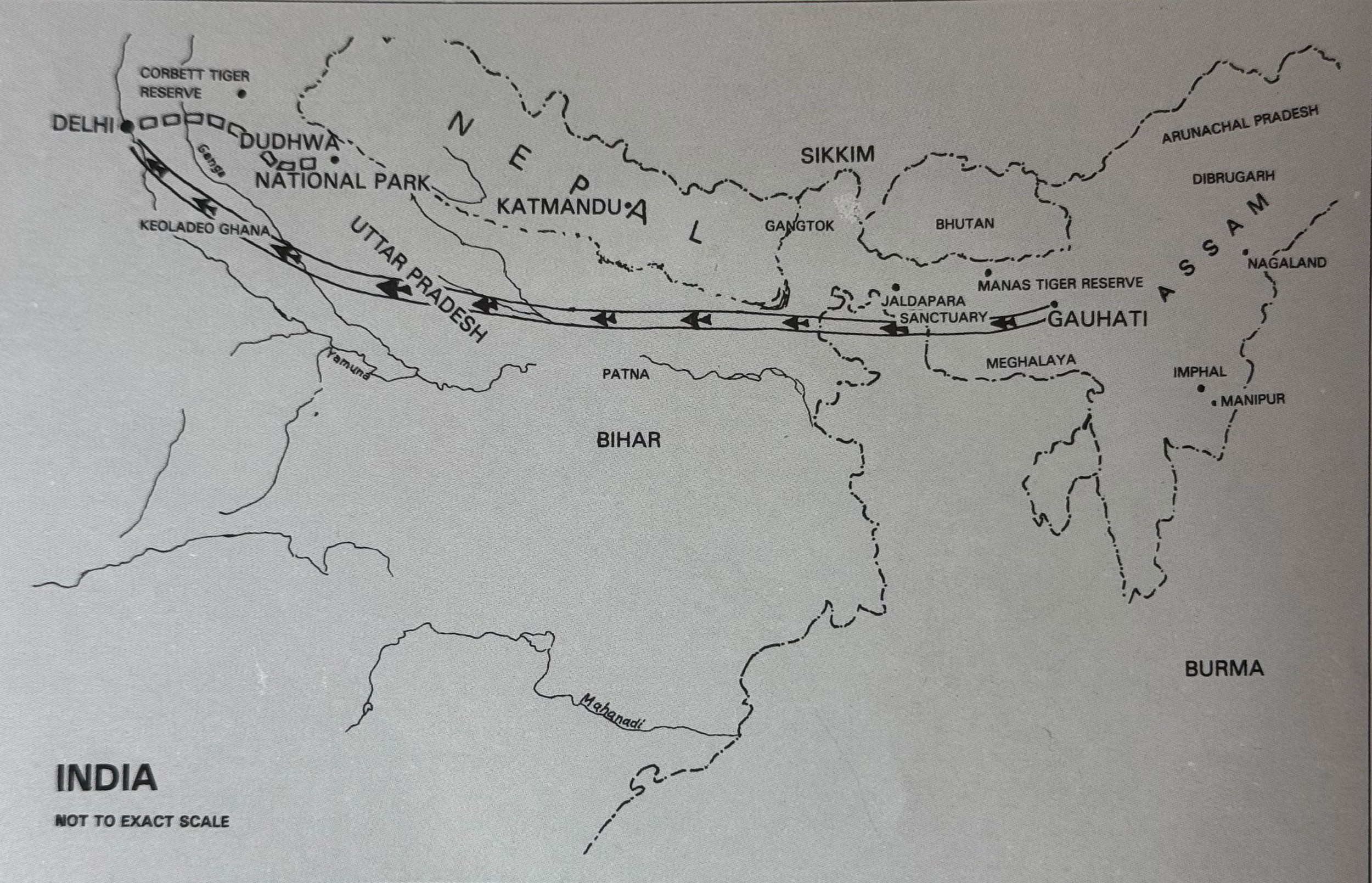

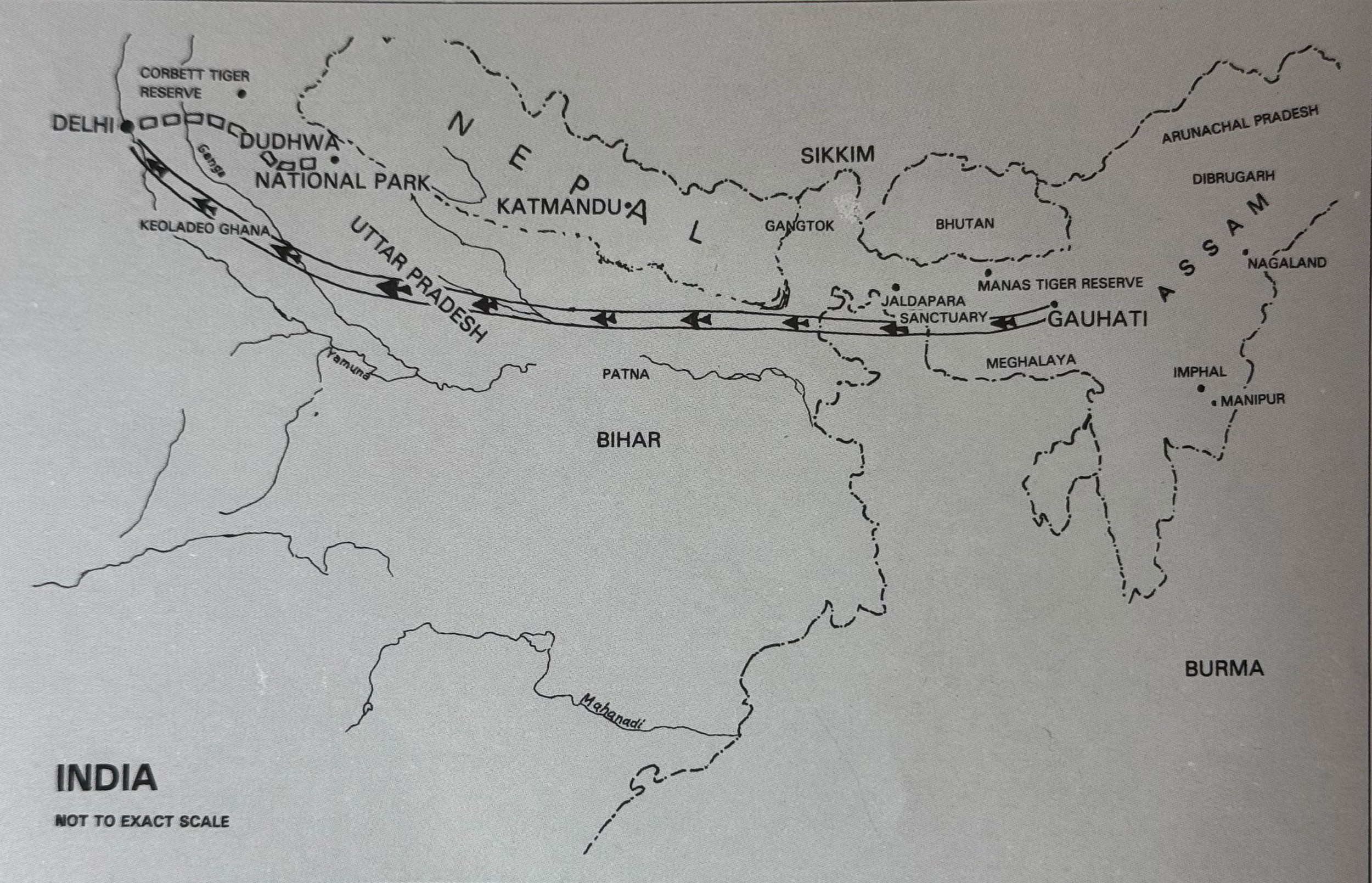

The flood plains of the Indus, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers have been the home of the Great Indian One-horned rhinoceros long before man was even a prospect In the scheme of evolutionary events. Cornered, harassed and hunted, these living relics from pre-history now lead endangered existences in a small corner of the Indian subcontinent. Around 300 remain in Chitwan, Nepal; perhaps 40 in Jaldapara, W. Bengal and the rest, somewhat over a thousand animals, are to be found in Kaziranga, Laokhwa, Manas, Orang, Sonai Rupai and a few other scattered areas in Assam.

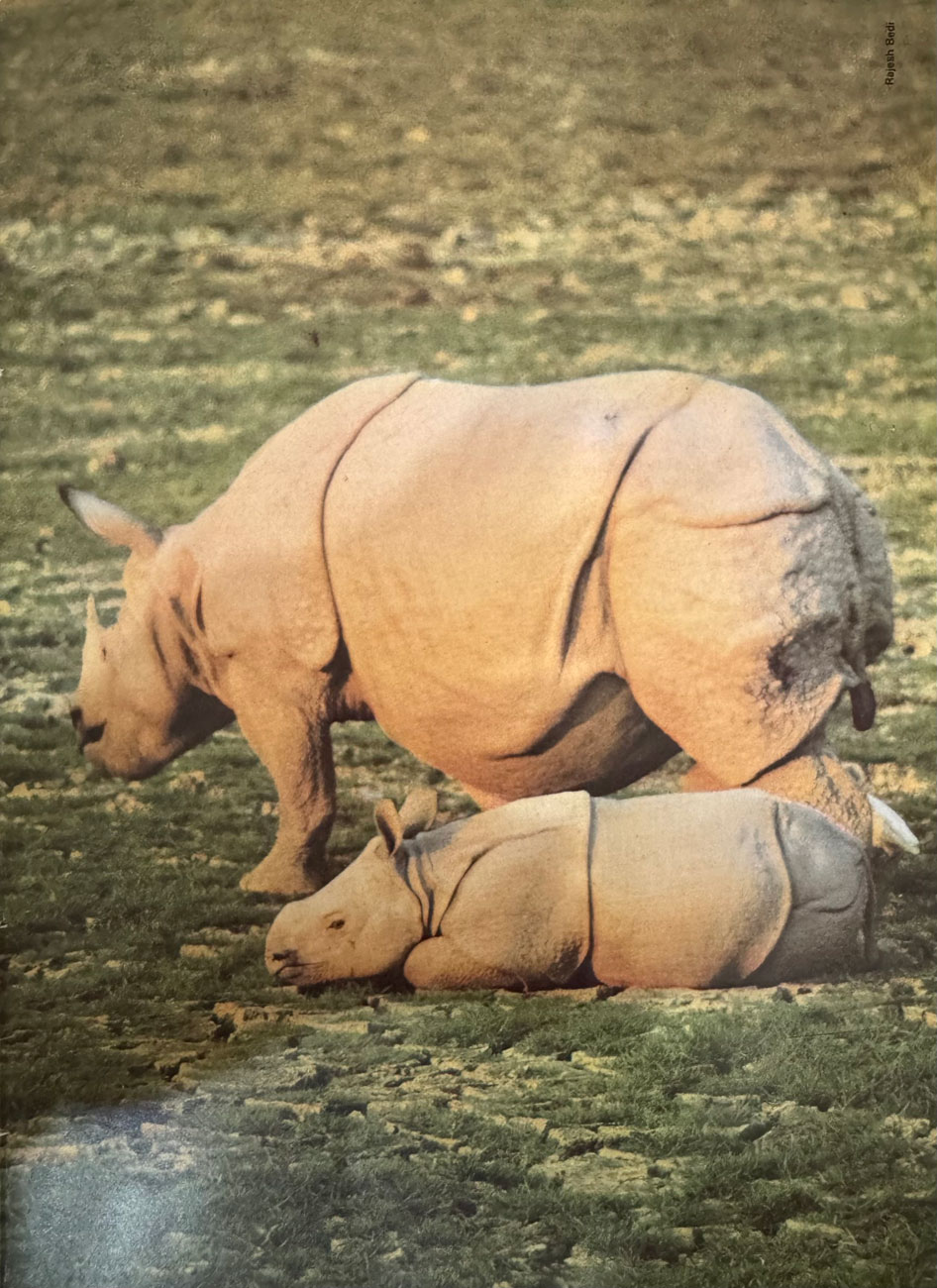

The author, a well-known naturalist and the Joint Secretary (Wildlife), Government of India, informs us of the chronological sequence of events that recently led to one of Asia's most significant conservation happenings -- the translocation of rhinos from Assam back to their former range in the Dudhwa National Park, U.P.

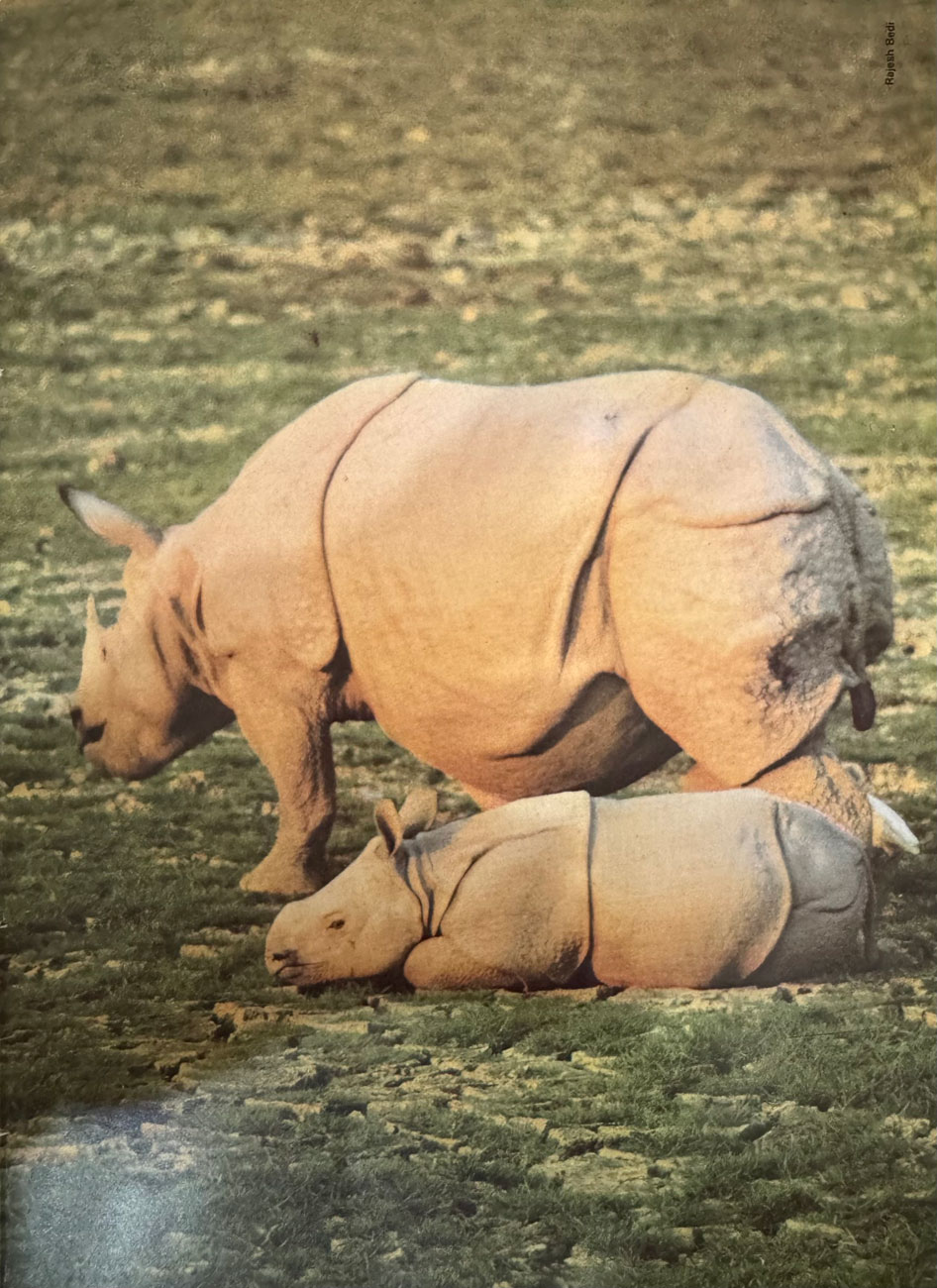

Photo: Rajesh Bedi.

We know too little about the long-term cause and effect ripples in Nature to predict the outcome of this small experiment. We must even reckon with the possibility that owing to some minor negligence on our part, the animals may not be able to hold their own in their new home for an extended period of time. Nevertheless, seeing how over five per cent of the total population of Rhinoceros unicornis were killed by poachers in the last 18 months, the necessity to find alternative, safer homes for the animals cannot be denied.

Right now, zoologists, botanists and naturalists should team up to monitor this experiment carefully. The experience thus gained should be put to use for future rhino translocations to Dudhwa.

The whole world looks at this bold and critical operation with great interest, for in a general atmosphere of gloom this step shines like a beacon of hope.

Five dust-laden trucks, carrying an equal number of rhinos, rumbled into Dudhwa in the very early hours of April 1, 1984, after an 18-hour journey from Delhi. The five rhinos had earlier performed an historic flight in a specially chartered Aeroflot cargo aircraft hired by the Government of India to fly them from Gauhati to Delhi. Accompanying them in flight was a small party headed by the Director (Wildlife), Government of India, who confirmed that the rhinos posed virtually no problems en route and that the two-and-a-half hour journey, sitting within touching distance of the `armoured' animals, was exciting and memorable. On arrival at New Delhi's Palam airport, the rhinos were given a VIP reception by a crowd of enthusiasts. The Union Deputy Minister of Environment, Mr. Digvijay Sinh, and the Forest Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Mr. Sanjay Singh, were also present and looked pleased at the outcome of their hectic efforts over the last few months.

Photo: Ashish Chandola

But why the fuss? Why Dudhwa? What next? These very legitimate questions are still uppermost in the minds of many people, and certainly need to be answered. There are four main reasons why this episode must be recognised as historic. First, it is easily one of the largest operation of its kind ever undertaken in the sub-continent. "If it succeeds, it will change the concept of wildlife management in the region," said one wildlife expert. Secondly, it follows soon after the adoption of the National Wildlife Action Plan (which gives priority to the reintroduction of endangered and threatened species) and therefore lends tremendous credibility to the intentions and capabilities of the Government of India. Thirdly, there is world-wide concern about the status of the rhino, leading to an international campaign during 1982, which was called the `Year of the Rhino'. And finally, the arrival of the rhinos at Dudhwa was a `home coming' of sorts in as much as they were returning to an area which was once the natural home of the rhino until about a hundred years ago.

It is interesting to note that the world's two largest land animals alive today -- the elephant and the rhinoceros -- are found only in Africa and Asia, where they have existed from pre-historic times. Until a century ago they were in great abundance on both these continents. Now, however, there is considerable concern about the survival of these animals and special efforts must necessarily be made to save them from extinction. It is in this context that India's rhino reintroduction programme has great relevance.

A recent position statement prepared by the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) defines `reintroduction' as "the international movement of an organism into a part of its native range from which it has disappeared or become extinct in historic times as a result of human activities.

Photo: Ashish Chandola.

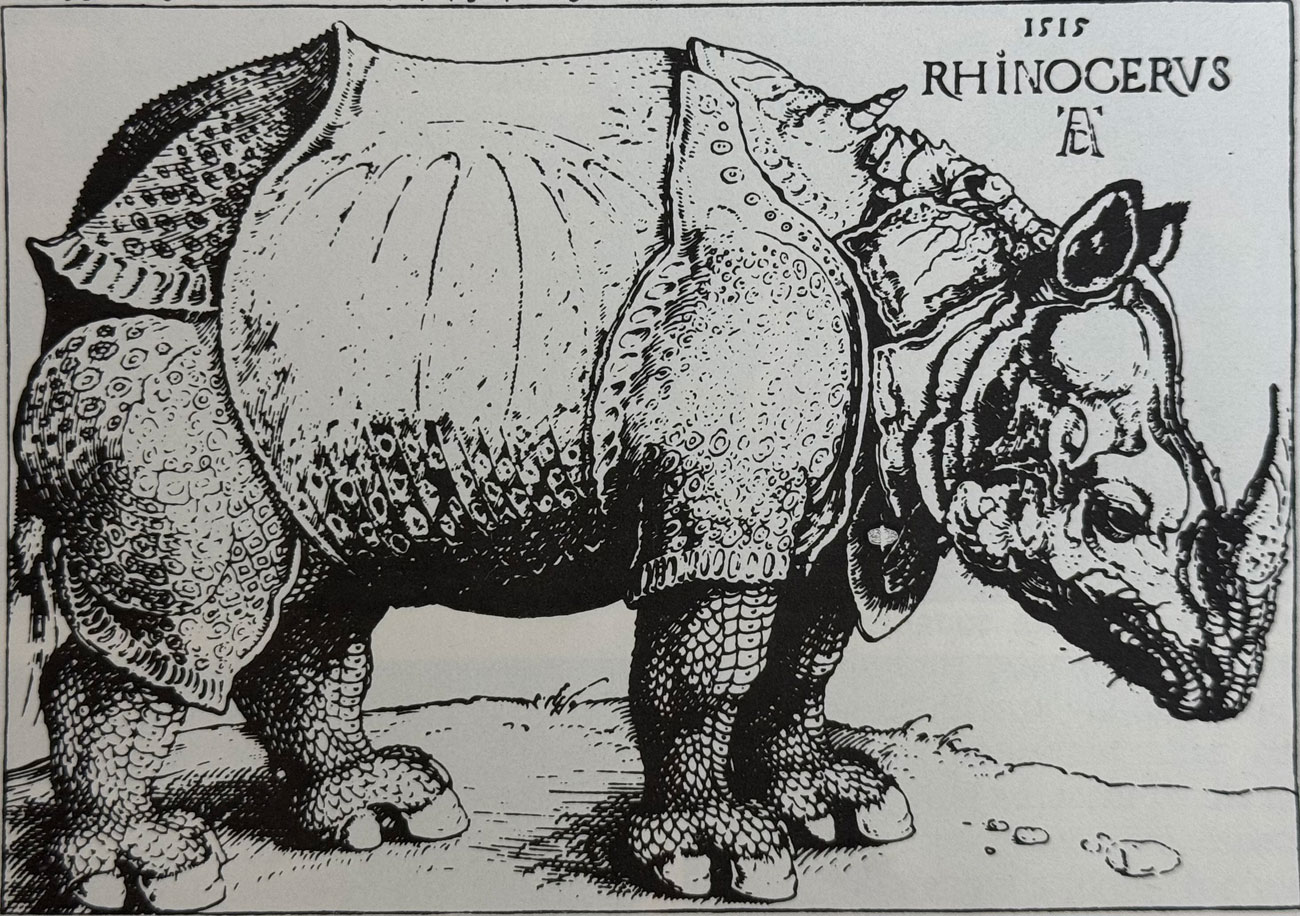

Let us now look at the former range of distribution of the rhino in India. Rhino seals have been found at Mohenjodaro (now in West Pakistan), dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation about five thousand years ago. In the medieval period there are records of Timurlane, the Mongol invader, hunting many rhinos on the frontiers of Kashmir around 1398 A.D. When he marched in to Delhi, Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud came out to receive him with his retinue which included 12 rhinos! In the beginning of the 16th century, Babur invaded India and founded the Mughal Empire. His memoirs, the Babur-namah, carry several accounts of rhino-hunting as far west as Peshawar and near the Khyber Pass.

At one place, it is recorded:

"The rhinoceros..... is a large animal equal in bulk to perhaps three buffaloes..... It is more ferocious than the elephant and cannot be made obedient and submissive. There are masses of them in the Peshawar and Hashnagar jungles, so too between the Sind river and the jungles of the Bhira country. Masses there are also on the banks of the Saru river in Hindustan. Some were killed in the Peshawar and Hashnagar jungles in our wars on Hindustan."

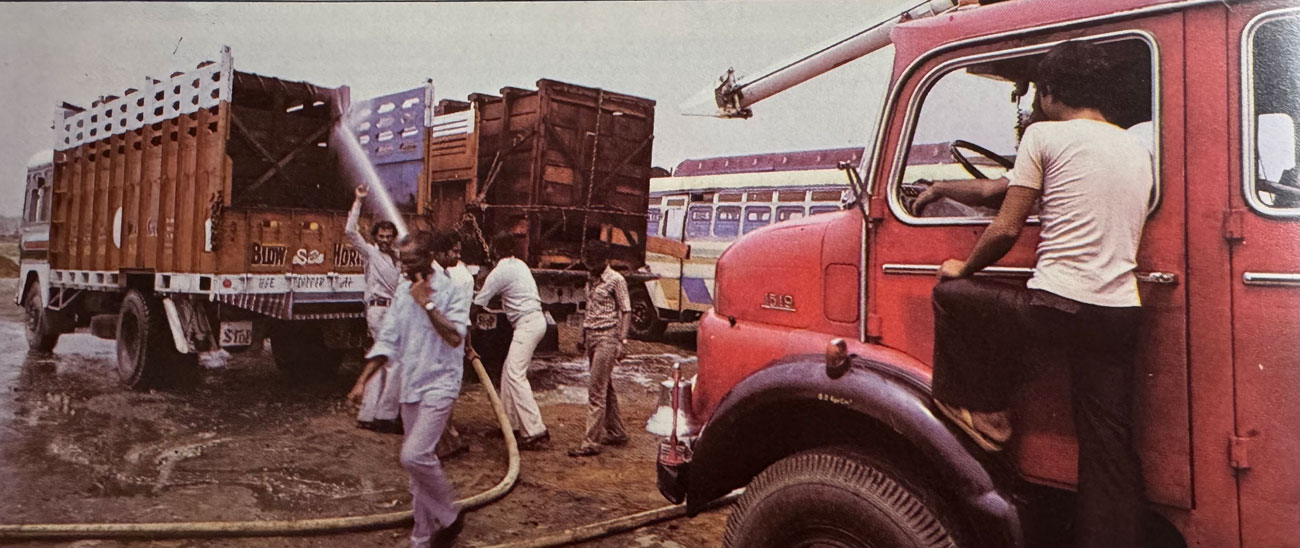

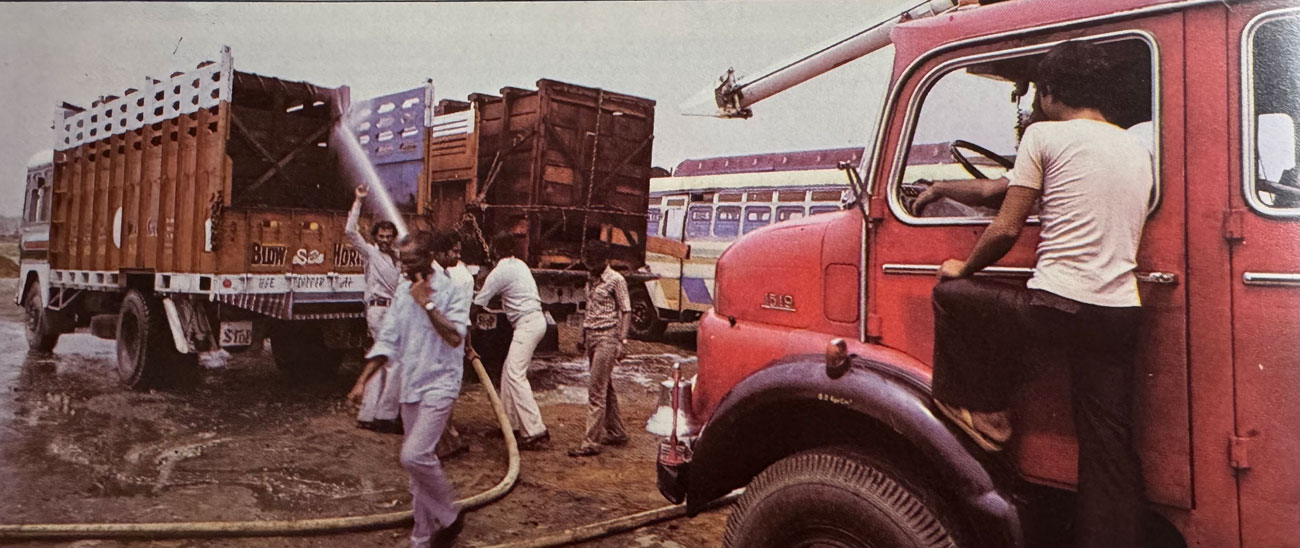

Prior to being loaded on to the specially chartered aircraft, the rhino are cooled down by co-operative fire-brigade personnel. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

Babur was obviously referring to the Great One-horned rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis), the largest and best-known of the three Asiatic species of rhino, now found only in parts of India and Nepal. The other two Asiatic species -- the Javan or Lesser One-horned rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) and the Sumatran Two-horned rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) -- were also once found on the Indian sub-continent until perhaps the beginning of the 19th century. However, it is only the Greater One-horned species, popularly known as the Indian rhino, which has survived on the sub-continent, though in greatly reduced numbers.

The former range of the Indian rhino extended all along the foothills of the Himalayas, particularly the Terai region and the valleys of the great rivers -- the Indus, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra. By the turn of the century, hunting and poaching for sport, hide and horn as well as large-scale habitat conversion for cultivation led to a drastic reduction in the rhino population and now only about 1,500 animals survive in parts of India (about 1,200) and Nepal (about 300). Most of the population in Nepal is restricted to the Chitwan National Park. In India, almost the entire population is in Assam, the Kaziranga National Park being the main stronghold, (1978 census -- 960).

A conservation odyssey begins, with the rhinos being slowly and carefully placed on board their waiting transport. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

In August, 1979, the Asian Rhino Specialist Group of the IUCN Survival Service Commission (now called the Species Survival Commission) met in Bangkok to analyse the situation with regard to the three Asian rhino species and to work out specific proposals for their long-term survival. As far as the Indian rhino was concerned, the specialist group, headed by Prof. R. Schenkel of the University of Basel (Switzerland), urged the need to monitor all local population units and "to identify new areas suitable to harbour additional population units and to establish such units by translocating rhinos from overpopulated areas. This will, at the same time, reduce friction between rhinos and people, and broaden the basis for the species' survival." It was their opinion that the selection of suitable areas for establishing additional population units of the species should preferably be in the rhino's former distribution range. It was further stated that "as Kaziranga is already now overpopulated, a pilot action is urgent to relieve Kaziranga and to acquire experience in translocation."

Shortly thereafter, in November 1979, the Wildlife Status Evaluation Committee of the Indian Board for Wildlife met in New Delhi and appointed a sub-committee of experts to consider and recommend alternative areas for the translocation of some rhinos from those parts of Assam where a reduction of the rhino population was considered advisable. The proposal was mooted by the Chief Conservator of Forests, Assam, who also participated in the meeting. The chairman of the rhino sub-committee was Dr. J.B. Sale, a F.A.O. specialist in wildlife management, with more than 25 years experience in Africa and Asia, who is currently the Chief Technical Officer at the Wildlife Institute of India. The sub-committee got down to business straight away and established the following main ecological criteria for the reintroduction of the Indian rhino:-

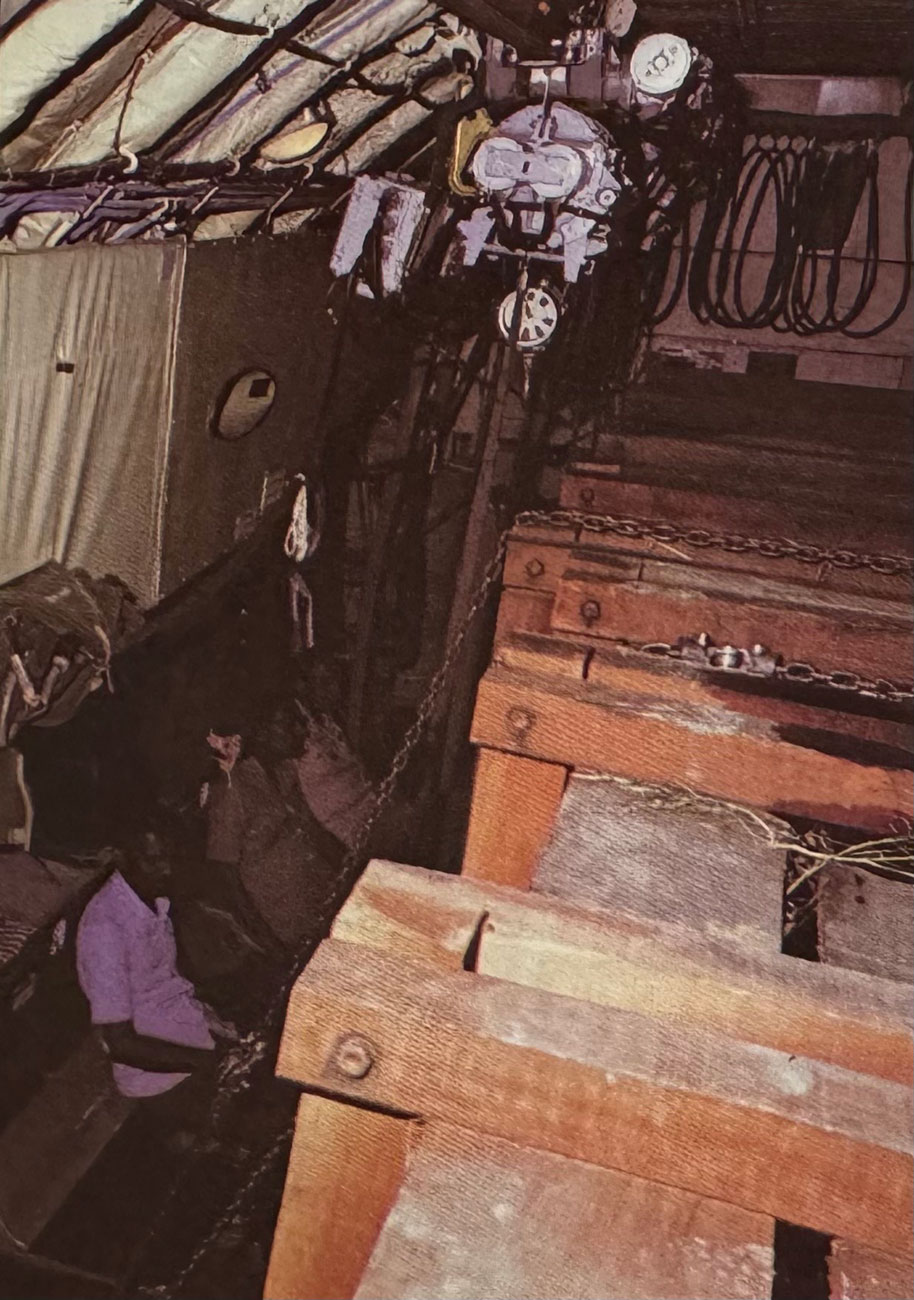

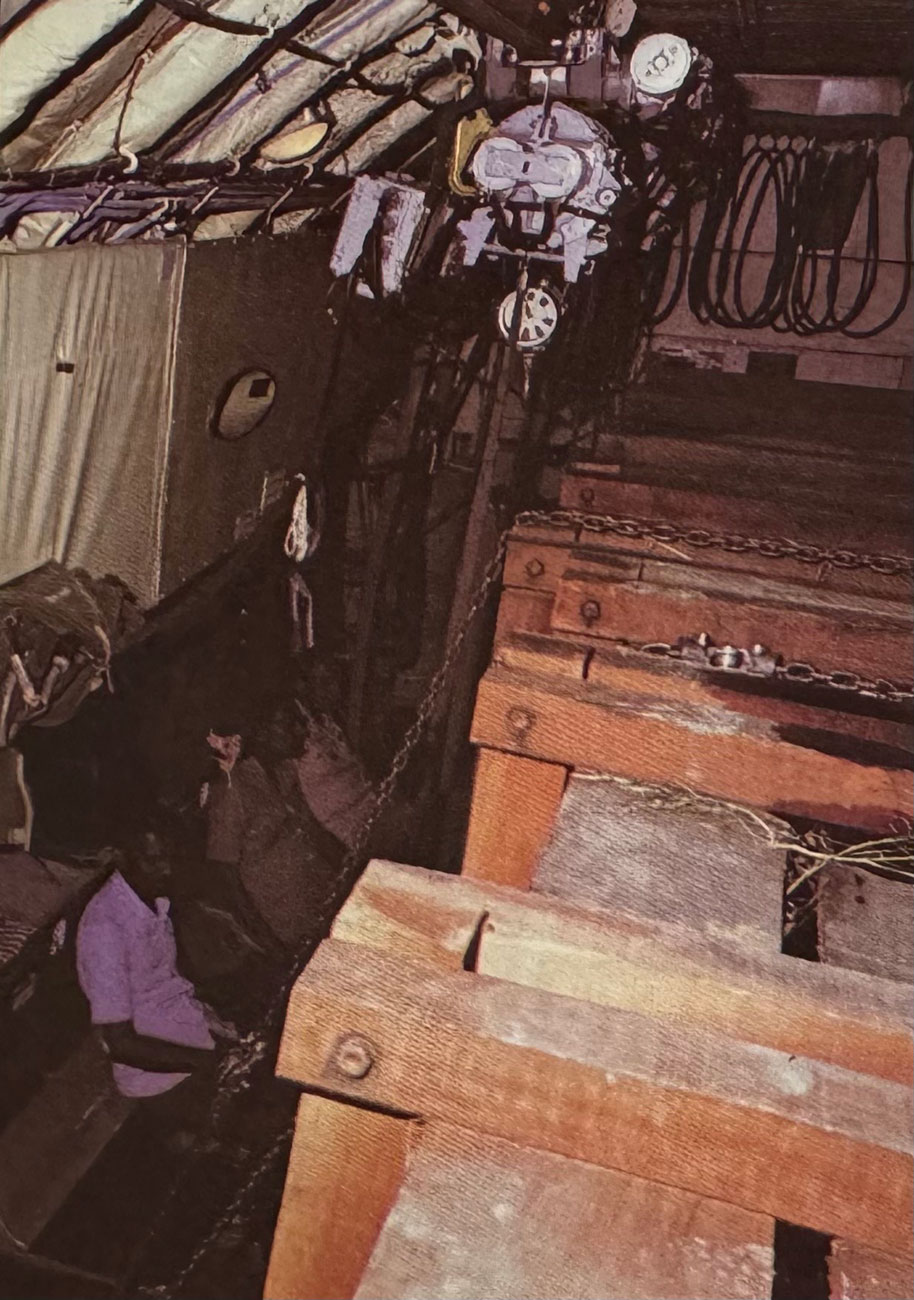

A view from the `belly of the beast'. Transport planes have been used to move men and materials around the world for years, but this unique cargo was a `first' in India. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

(i) Diversity of habitat, including flooded grassland with a variety of food plants.

(ii) Ample shade and water for wallowing (and drinking), especially in the hot season.

(iii) Protection from all forms of human disturbance and harassment, including pollution, poaching and the introduction of disease via domestic stock. It is equally important that conflict with cultivation adjacent to the areas of reintroduction be avoided, especially in view of the rhino's liking for crops such as paddy and sugarcane.

Prof. Schenkel, who was visiting India, was requested to visit Assam to give his assessment of the situation there. He gave the following opinion: "From the point of view of species conservation, it would be highly desirable to create more local rhino populations in suitable, well-protected areas. This has been proposed by the Asian Rhino Specialist Group, of which Mr. Lahan from Assam is a member. All the authorities in Assam responsible for rhino conservation specially also the Chief Conservator of Forests, Mr. Goswami, support the idea." He further suggested that "it should be possible to specially select those rhinos for translocation, which have been in small pockets, in permanent conflict with man and are extremely difficult to protect." In a subsequent report, Prof. Schenkel stated that "Dudhwa is the area most suitable for establishing a new local population of Indian rhinoceros, The area is protected, large enough and contains suitable habitat."

Not exactly a luxury charter. The author, seated furthest from the camera, waits touch down at a Palam. The solidly-constructed crates are chained down securely to prevent movement in the event of air turbulence. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

With a view to establish appropriate capture, handling and translocation techniques and to train personnel in such an operation, field trials were carried out in Assam between January 17 and February 12, 1980, by Dr. J.B. Sale and Dr. M.H. Woodford (Consultant Wildlife Veterinarian) with the help and full co-operation of the Assamese authorities. Five rhinos were successfully immobilised, four of which were transferred to holding sites specially set up for this purpose. These trials demonstrated the usefulness of the drug immobilisation technique in the capture of Indian rhinos. Capture and transport procedures (upto the holding stage) were also developed and some training was imparted to field personnel and veterinarians.

Meanwhile the rhino sub-committee visited Dudhwa to assess its suitability as a reintroduction site. A team from the Botanical Survey of India led by Dr. P.K. Hajra was also commissioned to carry out a detailed survey of the vegetation of Dudhwa in its relation to rhino feeding ecology. This detailed study clearly established a number of floral elements common to Dudhwa (U.P.) and Kaziranga/Manas (Assam), both of which are excellent rhino habitats. A list of 14 plants (including grasses) eaten by rhinos in Assam were located in Dudhwa.

On the basis of the vegetation survey and other relevant factors, the rhino subcommittee came to the unanimous conclusion that "Dudhwa National Park contains suitable habitat for a population of Indian rhinoceros." In its report submitted to the Government of India in July, 1981, the subcommittee noted that the Indian rhino had been present in this area until the 1870s; the last record being of one shot in the Pilibhit District in 1878.

At Palam, the rhinos were accorded a VIP welcome. The animals posed no problems in flight and would now be mounted one-to-a-truck to move them to their new home in Dudhwa. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

Here, it is pertinent to mention that the management history of the forests of Dudhwa National Park in the Lakhimpur-Kheri District of Uttar Pradesh dates back to the second half of the 19th century when these private forests were taken over by the Government. These forests were subsequently declared as `Reserved Forests' under the Indian Forest Act in January 1937. The first working plan was prepared in the year 1886, which led to some measure of protection to the wildlife habitats. However, on account of hunting and heavy grazing pressure, the status of the forests as well as the wildlife contained therein deteriorated. It was only as late as 1958 that a sanctuary for swamp deer was constituted in the area. Called the Sonaripur Sanctuary, it extended over a mere 15,766 acres. The area of the sanctuary was extended in 1963 to cover 212 sq. km., and it was declared as the Dudhwa Sanctuary. The protection measures undertaken in the sanctuary proved beneficial to the swamp deer as well as other wildlife species and, recognising the ecological importance of these forests, the Government of Uttar Pradesh notified an area of 490 sq. km. under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, as the Dudhwa National Park, on February 1, 1977. (An area of about 123 sq. km. acts as a buffer zone for the park, which thus has a total area of about 613 sq. km.). The forests house some of the best Sal (Shorea robusta) stands in the country. These are interspersed with grass meadows, ponds, lakes and other perennial sources of water. The suitability of such a habitat for wildlife is well reflected in the diversity of fauna and flora to be found here.

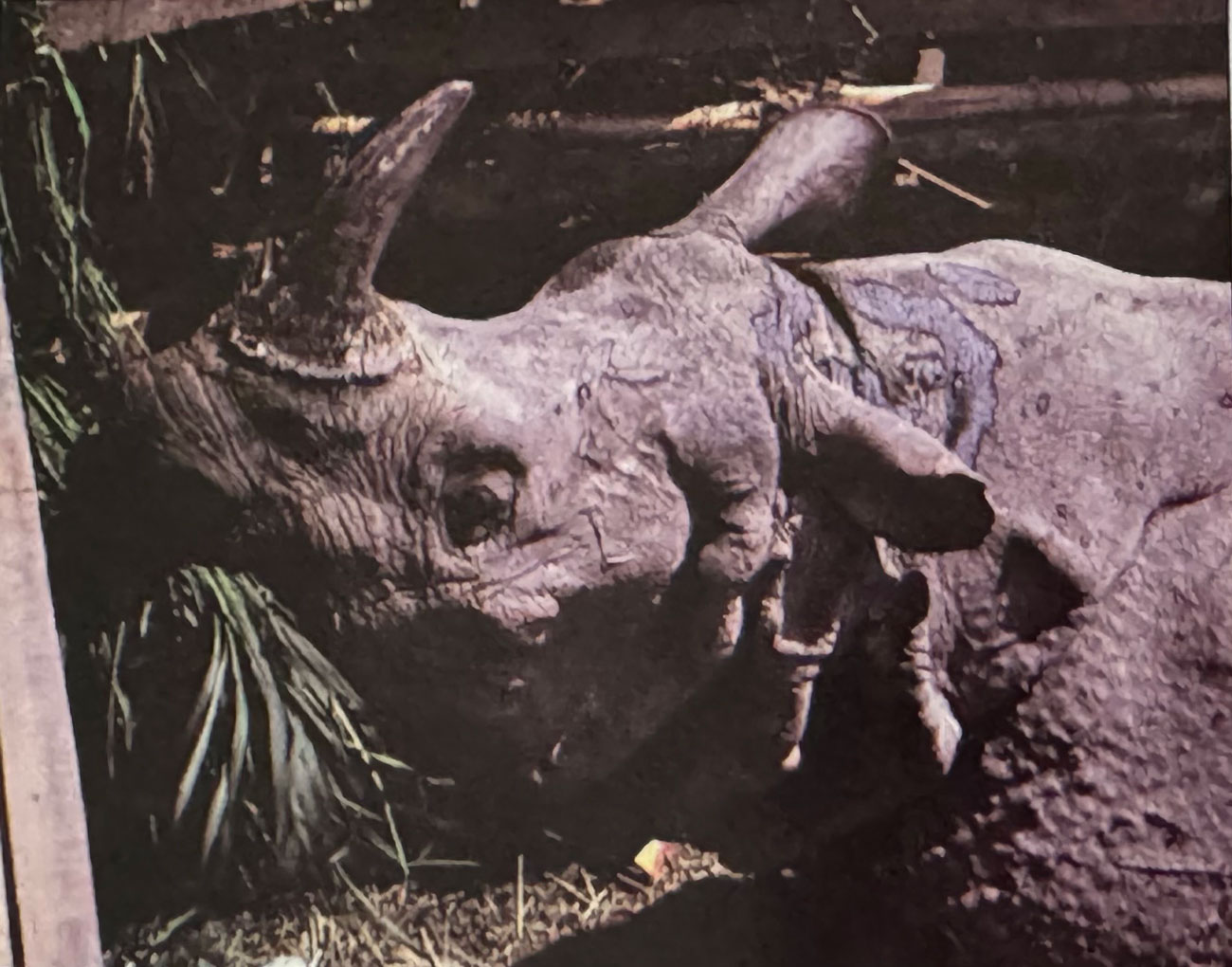

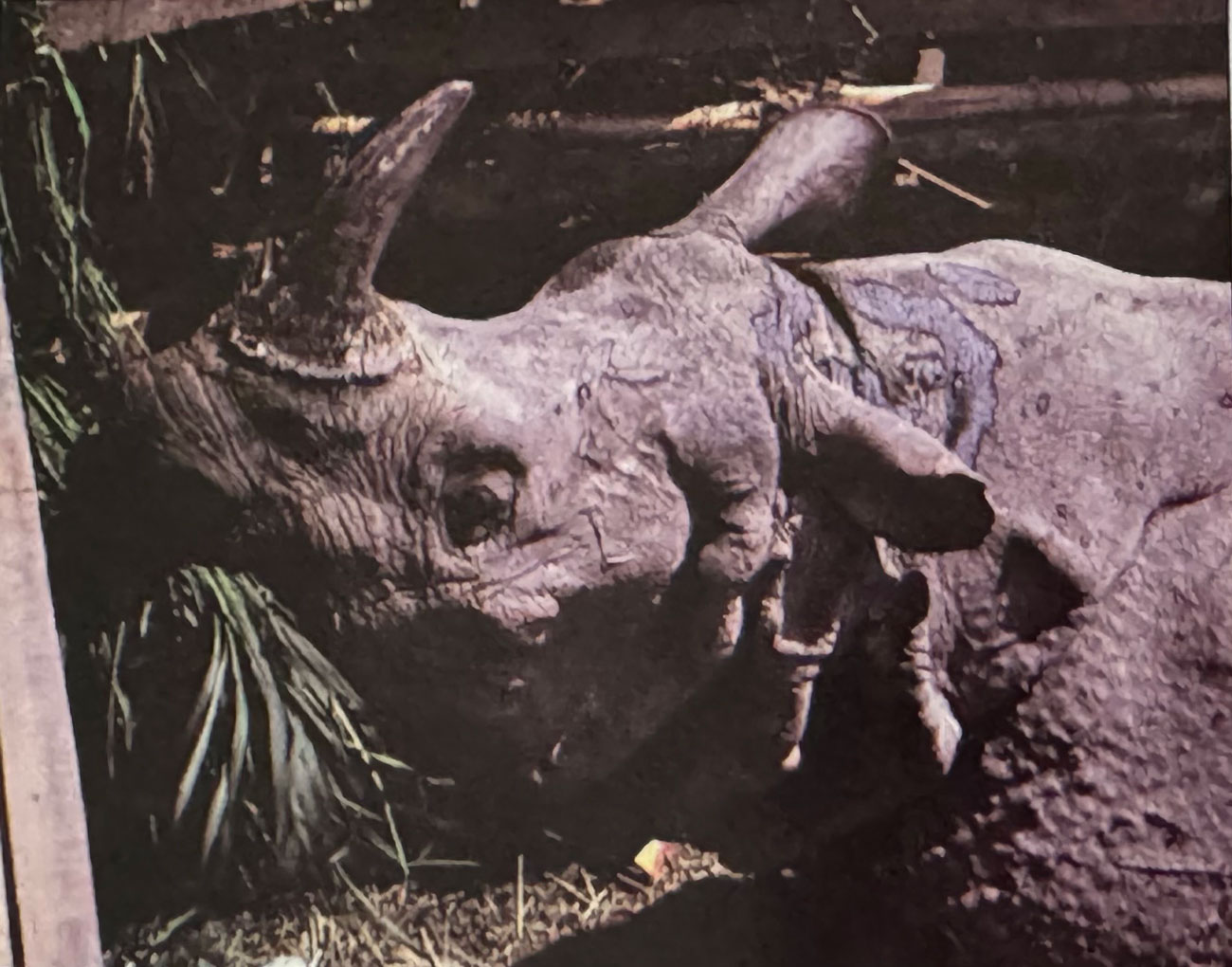

Two days after being capture a proudly horned rhino hungrily accepts a grassy meal. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

The rhino sub-committee had recommended a number of measures to be taken, prior to any reintroduction of rhinos in Dudhwa. Most of these related to better management through improved protection and enforcement, as well as the provision of special staff and equipment. Additionally, a trench-cum-fence was to be constructed all round the 19 sq. km. area in which the rhinos were to be released. The Government of Uttar Pradesh was urged to initiate the necessary action to implement the above recommendations without delay.

On August 19, 1981, the standing committee of the Indian Board for Wildlife met at New Delhi under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister. The report of the rhino sub-committee was approved and further action as recommended was asked to be taken right away.

A Project Implementation Committee headed by the Director (Wildlife), Government of India, was then set up. Meanwhile, the IUCN and WWF-International expressed full support for the project, specially in the context of 1982 being `The Year of the Rhino'.

When shifted to Dudhwa the rhinos were housed in an elaborately designed paddock from which they were released into the wild. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

Then followed the preparatory phase spanning the whole of the open season of 1981-82 during which U.P. authorities took action. A special trench 3m x 2m x 1.5m was dug around most of the selected area. Subsequently, in 1983, the trench was reinforced in parts by an electric fence, devised under the expert guidance of F.A.O. consultant, Robert Piesse from Australia. The electric fence, in fact, proved to be far more economical than the trench; the former costing only about Rs.4,500.00 per km., as compared to the Rs.50,000.00 to Rs.75,000.00 per km. (depending on the terrain) required for the latter.

While preparations were afoot at Dudhwa, the Government of Assam expressed some reservations about the project and called for a closer look at some of the recommendations of the rhino subcommittee. Hence, discussions were arranged between the members of the sub-committee and representatives of the Assam Government. The sub-committee visited Assam and meetings were held at Kaziranga and Manas in December, 1982. This was followed by a visit to Dudhwa in April, 1983, (a team of four experts from Assam were also present) to assess the suitability of Dudhwa for the proposed rhino reintroduction.

For the first time in over a century rhino and elephant confront each other in Dudhwa's lush grass and jungle habitat. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

Still more meetings followed at the officials' level and then a series of meetings in Delhi and Gauhati between the Forest Ministers of U.P. and Assam with the Union Deputy Minister of Environment during the months of September/October 1983. Meanwhile, the standing committee of the Indian Board for Wildlife met again in New Delhi on September 13, 1983, under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister, and strongly endorsed the need for urgent action on the matter, specially in the context of an increase in the incidence of poaching of rhinos in Assam. The Chief Minister of Assam was then approached. He took a keen interest and finally gave his approval to make available six rhinos for experimental reintroduction at Dudhwa National Park. The Government of Assam also agreed to provide the necessary facilities for the capture and transport of the rhinos inside the state. The Pobitara Sanctuary and an area surrounding the Nowgong Forest Division, about 60 km. from Gauhati, were selected for the capture operation.

A capture team, consisting of carefully chosen personnel from Assam and U.P. wildlife organisations, left for the selected area in the first week of March, 1984. The team led by Dr. J.B. Sale and assisted by two veterinarians was successful in capturing five rhinos (two males and three females) between March 15 and 21, 1984. Four of them were `problem' animals that habitually frequented cultivation. All the five animals were captured by darting, using `Immobilon', which was reversed by `Revivon'. They were then carried to the holding site, where they were released into individual stockades.

After about eight days, the five rhinos were placed into specially designed wooden crates fabricated to stringent specifications. They were then trucked to Gauhati airport on the morning of March 30, 1984. Here they were loaded into an Aeroflot IL 76 cargo aircraft specially chartered for the operation through Indian Airlines. Initial plans to airlift the rhinos from Gauhati to Lucknow or Bareilly could not materialise as the airfields at both these places were not found suitable to take such a large aircraft. Three of the animals were given pre-flight sedation and all five behaved well during the two-and-a-half hour flight to New Delhi. After food and water at Delhi (Palam) airport, the crated animals were loaded onto trucks for the journey to Dudhwa, which took about 18 hours. Immediately on arrival at Dudhwa, the rhinos were released into individual stockades, where they were cared for by a U.P. team (including veterinarians) which had received special training in Assam during previous months. Freshly-cut local grasses were provided which were consumed readily by the rhinos.

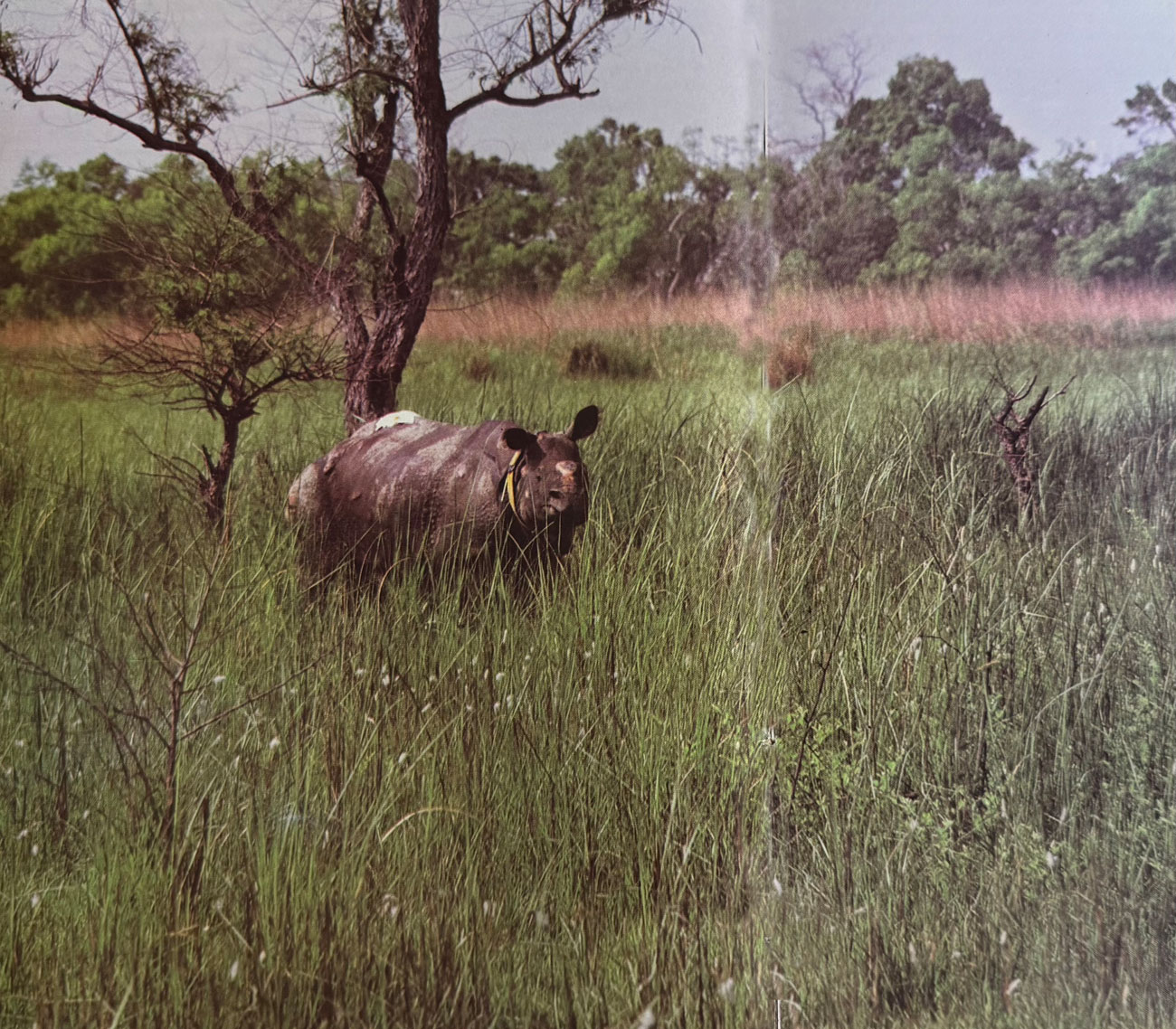

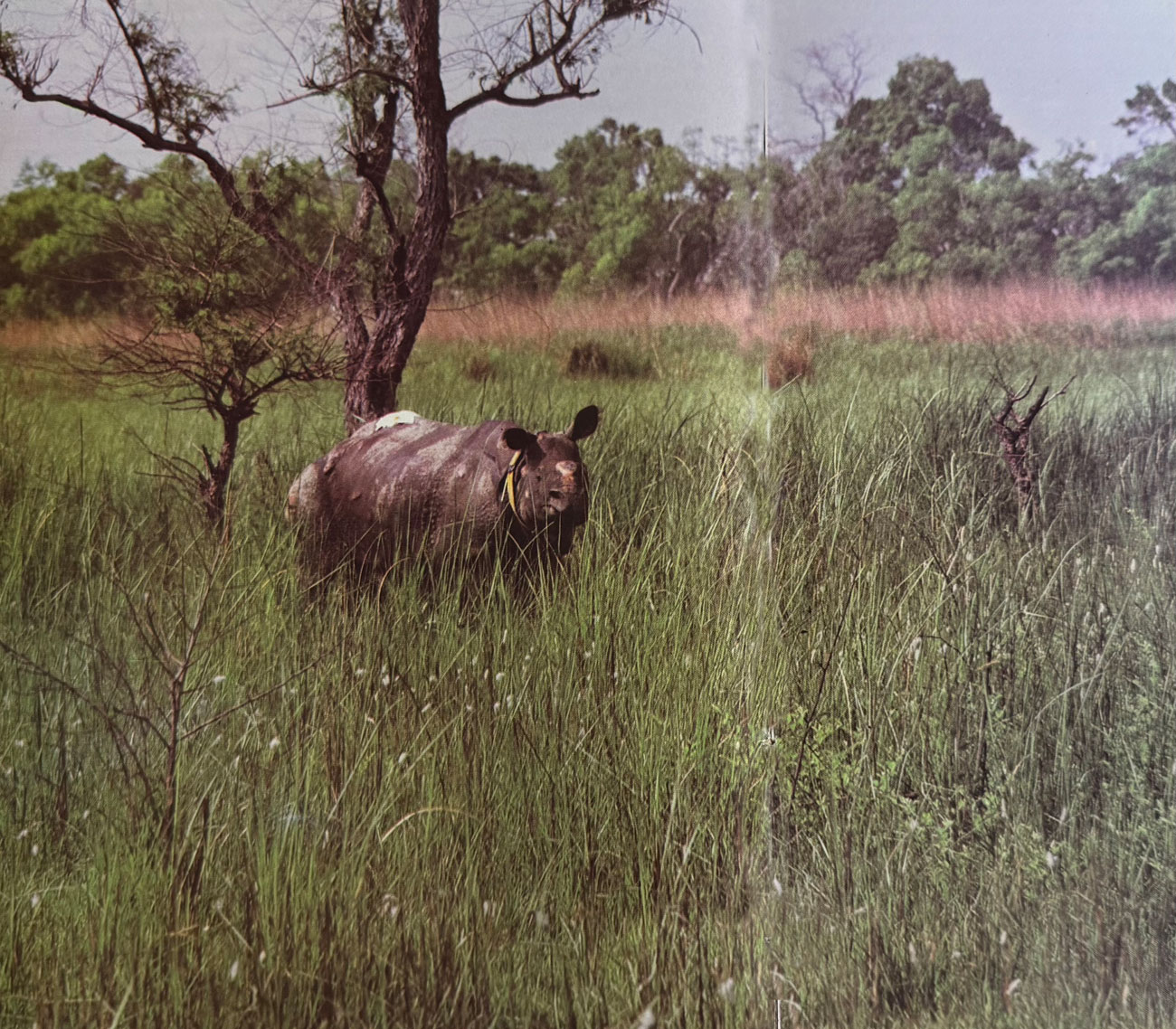

Free, but radio-collared, Asha, a female rhino peers cautiously back at photographer Ashish Chandola who travelled thousands of miles in the course of a few months to record the translocation exercise on film for posterity. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

After three weeks at Dudhwa the group, with the exception of a pregnant female who had resisted captivity and died tragically following a stressful abortion, was deemed fit for release. Three of the animals were let out into the specially fenced area on April 20, 1984, a large bull having been held back until the others had time to settle down. The male was released some days later after being radio-collared. The release area has abundant green grasses, shade and water to supply the animals' needs during the forthcoming summer period. The movement of each animal is being monitored daily by a special team set up for this purpose. The release area is under intensive watch and ward under the overall supervision of the Director, Dudhwa National Park. The electric fence has been adequately strengthened and its efficacy as a wildlife proof barrier is under test. The whole operation has evoked considerable interest both in India and abroad. The reactions of the local population have, so far, been favourable. What happens if and when any of the rhinos stray into the cultivated areas, a distinct possibility, remains to be seen. An educative and interpretative programme for the benefit of the locals is being mounted for this purpose.

Further releases of rhinos in Dudhwa will depend on the experience gained with the initial experiment. A release of 20 to 30 animals over a five-year period would be desirable to establish a viable breeding population. In this context the possibility of infusing new blood, by getting a few animals of the same species from Nepal, is worth exploring. The selected area of about 90 sq. km. is considered suitable to accommodate around 90 to 100 animals, based on a reasonable density-ratio of one rhino per sq. km.

To control the rhinos' range of movement, an electrified fence was constructed along selected sections of the jungle. The idea proved both economical and effective. Photo: Ashish Chandola.

Quite obviously the rhino reintroduction programme cannot end with the translocation and release of just these four rhinos in Dudhwa. This is, in fact, the take-off point for the development of an integrated conservation and management programme for the Great Indian rhinoceros in the country. For this purpose a research project has been drawn up, the main aim of which is to provide objective scientific data as the basis for improved management of the species in India. This will in turn have great significance for the region as a whole.

The research project will be funded by the Central Department of Environment, while the Wildlife Institute of India will be the nodal agency for its implementation. The project would be based at Kaziranga National Park in Assam but will cover all existing and potential rhino habitats in the country, including Dudhwa, the first new home for the Rhinoceros unicornis.

Viewed in its proper perspective, the return of the rhinos to Dudhwa is a political tribute to Centre-State understanding and coordination. It is also a tribute to the initiative of conservationists and naturalists both within and outside the Government. It could rightly be described as a giant step forward in implementing the recently adopted National Wildlife Action Plan and should pave the way for still more initiative in the field of wildlife management. No doubt, the ultimate success of the experiment will depend on a proper follow-up, based on sound scientific inputs, the support of concerned governments and the involvement of the local people. But, one way or another, history will record the fact that in Assam and Dudhwa in 1984 a conservation odyssey began.