'Not All Green Is Good'

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 10,

October 2025

By Dr. Chetan Misher and Purva Variyar

Great adaptability. Highly drought and disease tolerant. Deep-rooted. Fast growing. Hardy. Aggressive. ‘Mad’. Ideal traits in a plant evolved to live in hot and arid regions. But not so ideal for the ecosystems where the very plant is alien and invasive. The dry landscapes of certain Indian states such as Rajasthan and Gujarat have come to look different over the past many decades. Some parts look greener and denser, even when they are not supposed to, ecologically speaking. This greenery hides a problem – one caused by a very controversial species: Prosopis juliflora, an invasive Central-South American plant.

As we walk through a patch of scrub savanna in Rajasthan, that has been earmarked for restoration under Wildlife Conservation Trust’s (WCT) Ecosystem Restoration programme, the telltale signs of degradation are apparent – overgrazing, lopping, and alien invasion. The lattermost sign is rather stark. While many alien species plague this fragile, arid landscape, the dense green thickets of Prosopis juliflora stand out against the sparse, dry, brown foliage backdrop, typical of summer.

Just as all that glitters is not gold, not all green is good. In a misplaced and unscientific attempt to green and 'save' drylands, a fast-growing invasive species is now degrading them instead. Prosopis juliflora is transforming open natural ecosystems such as scrubs, savannas, and grasslands into woodlands, dominating them at the expense of native biodiversity.

The ecological integrity of dryland ecosystems, such as this scrub forest in Rajasthan, has been reshaped because of Prosopis juliflora, an invasive shrub. Photo: WCT.

Rise And Spread

Take Banni in Gujarat, for example. Here, the thorny intruder is known locally as gando bawar – the mad tree. Originally introduced by the Gujarat Forest Department in the 1960s and 1970s to combat soil salinity, provide fuelwood, and increase green cover, Prosopis juliflora has since taken over. Today, more than half of Banni’s once-thriving grasslands have metamorphosed into Prosopis juliflora-dominated wood-lands, irreversibly changing the ecological and socio-economic fabric of the region.

Once upon a time, in the arid regions of Rajasthan, seeds of this invasive plant were aerially scattered from airplanes and saplings planted along roads. Since then, Rajasthan witnessed a torrent spread of Prosopis juliflora in every direction not sparing even its rocky and saline terrains. Prosopis juliflora has since gone on to colonise several other Indian states including Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal.

Blame could be laid on the historical colonial forest management policies that officially classified grasslands and other Open Natural Ecosystems (ONEs) as ‘wastelands’. Unfortunately, Independent India’s forest protection and environmental policies have continued to classify and treat open ecosystems as such, further abetting the spread of Prosopis juliflora. Paradoxically, these ONEs or ‘wastelands’ make up nearly 10 per cent of India’s land yet receive little conservation attention. This estimate excludes the unique high-altitude open ecosystems, such as the Nilgiri sholas and the expansive trans-Himalayan regions, which are critical habitats for iconic species such as the snow leopard and Himalayan brown bear.

A dense thicket of Prosopis juliflora in Nimaaj, Rajasthan. Photo: Vijayant Khatri/WCT.

Ecological Villain or Prized Resource?

Evolution has endowed Prosopis juliflora with impressive ecological qualities making it extremely hardy, allowing it to thrive in the most inhospitable conditions of the hot, rocky, and saline habitats. It can even survive being chopped down in its entirety above ground. Its deep roots lodge firmly in the soil and cracks within rocks, allowing it to resprout and recolonise the area. In foreign, arid landscapes, this fast-growing, drought-hardy shrub outcompetes native plants, disrupting ecological balance in more ways than one.

Ecological surveys by WCT over the past year at RAAS-Chhatrasagar, one of our two restoration sites in Rajasthan, have helped gain deeper insights into the effects of the Prosopis juliflora invasion. Our preliminary findings reveal how Prosopis juliflora dominates large tracts of the dry landscape, reducing tree and shrub diversity and altering the plant composition. It has significantly altered soil chemistry and reduced insect and bird diversity. Woodlands dominated by native Acacia plants support a more diverse range of insects and birds, while Prosopis juliflora-dominated woodlands have a more uniform or homogeneous assemblage of species. This suggests stronger biodiversity in native habitats compared to areas dominated by the invasive Prosopis juliflora.

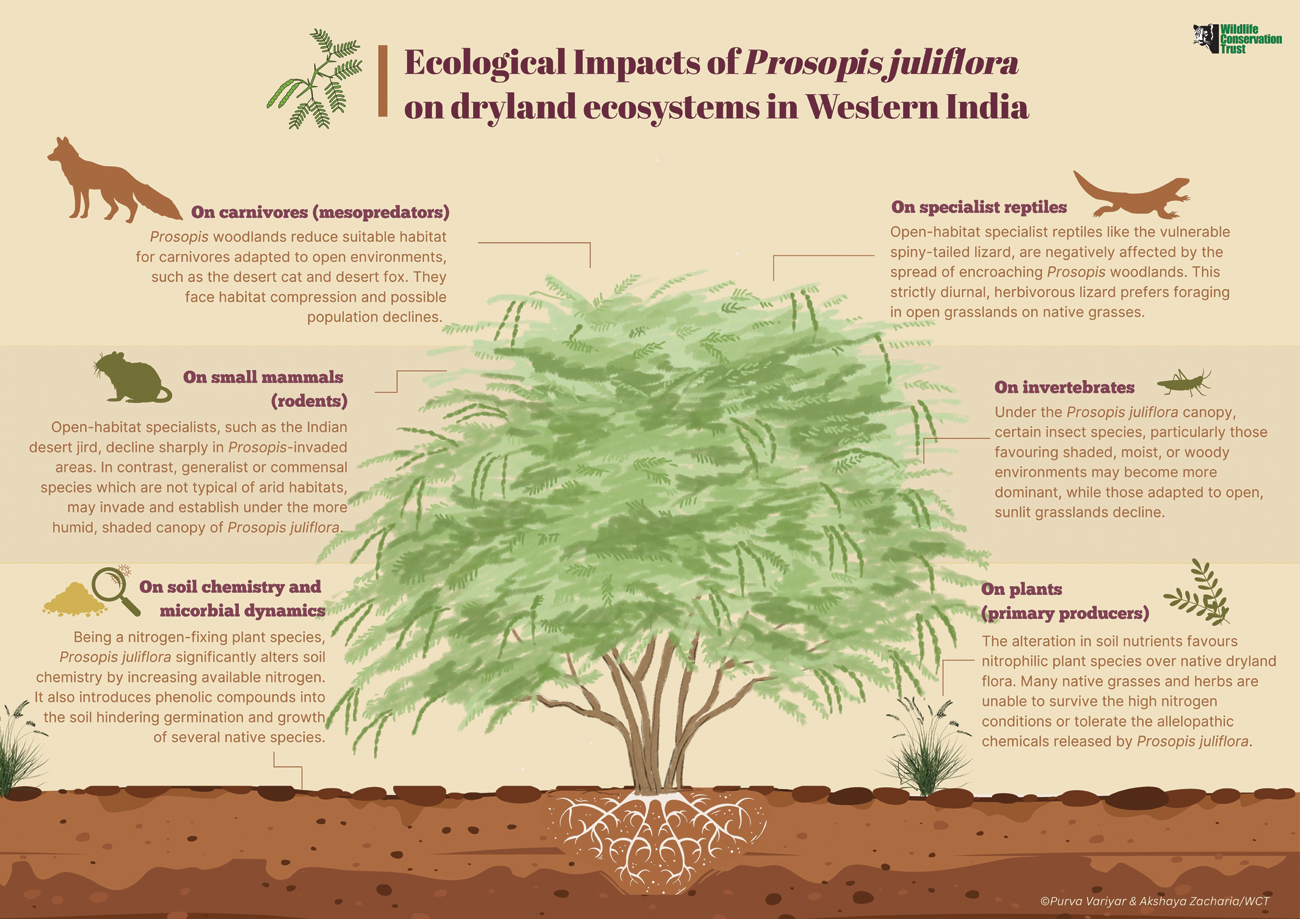

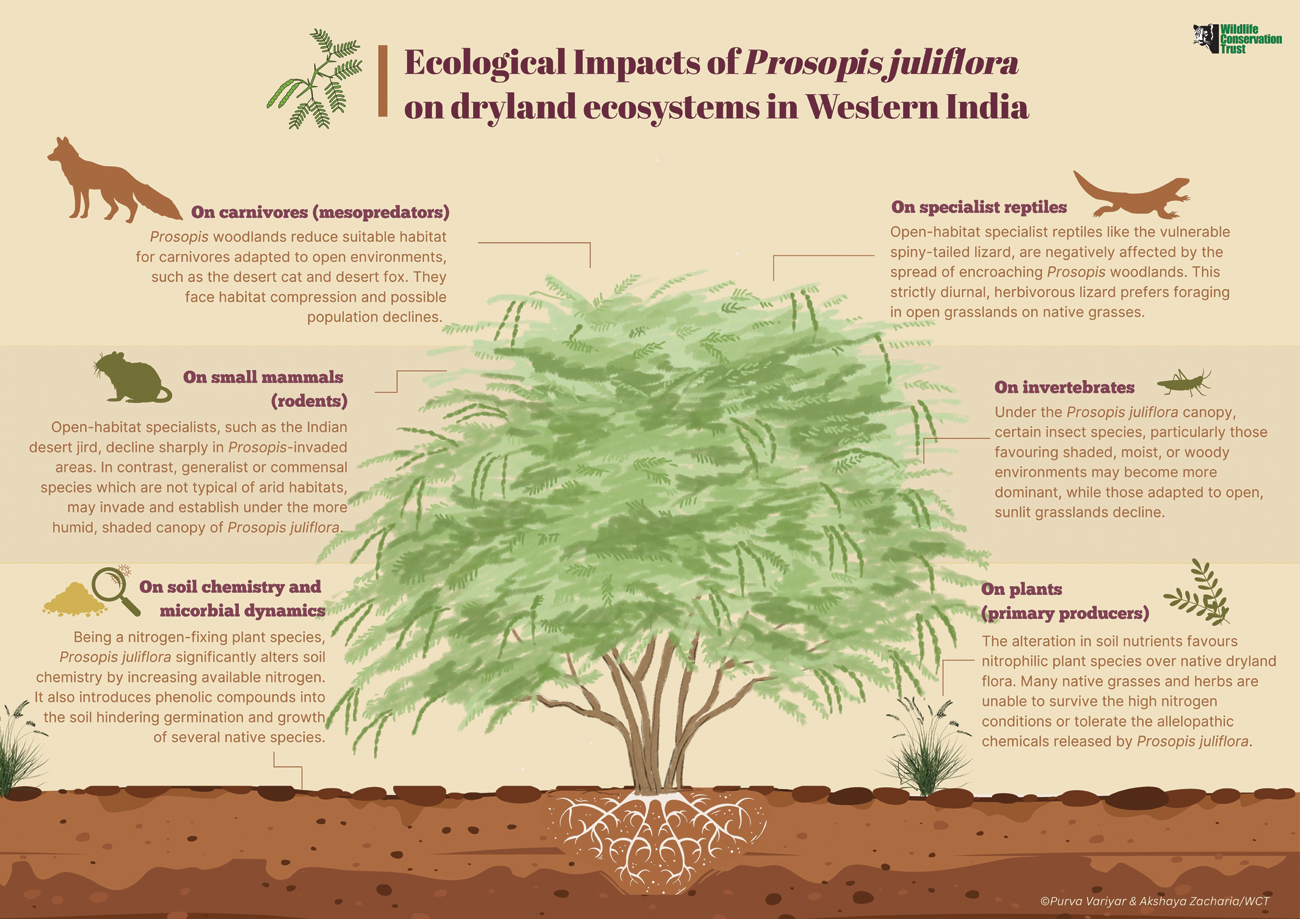

Photo: Purva Variyar & Akshsya Aacharia/WCT.

The invasion of Prosopis juliflora sets off a chain reaction across trophic levels – from soil microbes and plants to invertebrates, rodents, and carnivores – disrupting the ecological balance of dryland ecosystems. These cascading effects emphasise the urgency of managing Prosopis juliflora invasions not only for biodiversity conservation, but also for maintaining the functional integrity of dryland habitats.

Restoring lands colonised by Prosopis juliflora is far from a straightforward challenge. In the years since its deliberate introduction into India’s drylands and its ensuing proliferation, myriad communities have become dependent on it. Its negative ecological impacts aside, it has become an important source of livelihood and fuelwood in many parts of India. In Gujarat and Rajasthan, there has been a notable shift in local livelihoods. People now depend on it for charcoal production, and even harvest it for construction material, fencing, tools, and other daily needs. Removal of Prosopis juliflora from commons in order to restore dryland ecosystems is thus complicated.

As part of WCT’s ecological restoration efforts, dense thickets of Prosopis juliflora are being cleared manually, to make way for native plant species. Photo: WCT.

Fighting Back

RAAS-Chhatrasagar, a privately owned land invaded by Prosopis juliflora, located in the mountainous Aravalli landscape in Nimaaj, Rajasthan, has over the past year become a laboratory of sorts for WCT’s ecologists where restoration strategies are being tried and tested with the goal of revitalising the region. Our studies here have shown how Prosopis juliflora has altered soil composition, outcompeted native vegetation, and disrupted wildlife habitats.

But we are fighting back – removing it from identified areas to restore native ecosystems.This means understanding soil, vegetation, and wildlife dynamics – monitoring changes after removal and learning ways to improve future restoration. Through these ecosystem restoration efforts, WCT aims to assist the recovery of native vegetation and rebuild resilient savanna ecosystems around the Aravalli landscape through well-documented, scientific, and community-engaged restoration actions.

Ecological restoration is a long-term endeavour and comes with numerous challenges. It is a game of trial and error, and even setbacks, as we have already witnessed in the short time since the programme’s inception. In the course of ecological restoration work, we often find ourselves on a difficult path – battling against an aggressive invader such as Prosopis juliflora, uncertain rainfall, poor seed germination, or a failed planting season. There are moments when months of effort are lost to a single unexpected flood, or when painstakingly raised saplings wither in the harsh summer. At times, even defining what restoration means, or identifying a true reference ecosystem, becomes a challenge, especially in landscapes that have been shaped and reshaped by human hands over centuries. What we often call ‘pristine’ today is itself a legacy of historical interventions – outcomes of past protections, exclusions, or cultural practices that enabled certain ecosystems to take shape. In such contexts, there is rarely a straightforward path to restoration.

A restored site post-removal reveals an open landscape and resilient native tree species. Photo: WCT.

Additionally, the behaviour and physiology of different plants can make growing them in a nursery rather tricky. Dryland natives such as rohida and khejri, grow painfully slow. Others, such as ker and kheemp, don’t thrive in nurseries. Many native grasses are even harder to grow in a nursery.

But nothing worth doing has ever been easy. Restoration at the end becomes a practice grounded in learning by doing and doing while continuing to learn. Yet, it’s in the small victories that our hope takes root such as clearing dense Prosopis juliflora from waterbody banks and watching ground-perching birds return, or glimpsing apex predators that hint at an ecosystem’s enduring potential. These moments renew our resolve. These glimpses of recovery, however incremental, reaffirm our commitment to restoring balance in these fragile landscapes.

Dr. Chetan Misher is an ecologist whose research explores how new species reshape native wildlife communities and the ecological fabric of arid regions. Currently, he is working on ecosystem restoration with WCT in Rajasthan. Purva Variyar is a conservation and science writer and editor, and heads Communications and the WCT-BEES Grants Programme at the Wildlife Conservation Trust.