The Next Big Thing

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 26

No. 6,

June 2006

Text and photographs by Ian Lockwood

High Altitude Renewal: A celebration of shola-grasslands in the year of the kurinji.

It is mid-May on the 2,695 m. summit of Anai Mudi, southern India’s highest mountain. The monsoon is a few weeks away but clouds in the west hint of an afternoon shower. This morning it is marvelously clear and I have a commanding view over the largest undisturbed shola-grassland system left in the Western Ghats. Blue ghosts of hazy ranges point to the nearby Palni Hills and more distant Nilgiris across the Palghat gap. I recognise several prominent peaks that I climbed when I was growing up in the hill station of Kodaikanal. It was during those years that I first became interested in the ecology of the shola system. This year is particularly important for this threatened ecosystem because of the amazing mass blooming of the kurinji plant, a shrub endemic to these montane grasslands.

Anai Mudi’s large, windswept dome is crowned with a variety of grasses that have been nibbled down by herds of Nilgiri tahr Hemitragus hylocrius, the mountain goat endemic to the Western Ghats. There is a modest cairn, several clumps of dwarf bamboo Sinarudinaria microphylla and an ancient rhododendron tree on the eastern side. I am sitting comfortably in a clump of grass, scanning the lower hills for signs of animal life as a part of the annual wildlife census in the Eravikulam National Park. For the last week, I have been rising early to climb the highest peaks of the Anai Mudi massif. I am working with a Mudhuvan forest watcher named Palanisami and there are other teams out in different zones of the Park. Today, we have a tally of 37 Nilgiri tahr, including five solitary saddlebacks (adult males). For the last hour, I have been privy to an unusual scene – a tusker taking a nap on a hill far below me! At first, I fear that he is lying down to end his days in this stunning location but after a long hour he gets up and lumbers off into a shola.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the shola-grasslands ecosystem located in the higher ranges of the Western Ghats. It is home to several endangered species and a source of water to the thirsty plains. Just a decade or two ago, grasslands were designated as ‘wasteland’ by the forest department and only thought to be suitable for fuel-wood plantations. This unfortunate hangover from colonial times helped convert once vast areas of grasslands into relatively lifeless monoculture tree plantations. I personally feel connected to the decline of the shola-grasslands ecosystem. My grandfather and father had hiked and photographed in the undisturbed Palnis in the 1930s and 50s. By the time I was a student exploring the same areas in the 1980s, many of their favourite spots had been blanketed by dull eucalyptus, pine and wattle plantations! Since then, as I have visited different parts of the Western Ghats, I’ve been acutely aware of the fragile status and delicate nature of the shola system.

A spectacular view of the Cardomom Hills where a rhododendron tree Rhododendron arbrouem nilgiricum clings to a steep hillside.

Features of the shola-grasslands

The shola-grassland system is found above 1,700 m. in the highest reaches of the southern Western Ghats (note: sometimes a figure of 1,800 m. is used and this varies depending on latitude and local topographical and climatic conditions). Because most of the higher ranges are found south of the Nilgiri Hills, the ecosystem is a feature of the southern Western Ghats (as opposed to the northern Ghats or Sahyadris). Significant shola-grassland systems are located in the Nilgiri, Palni, Anaimalai Hills and what is known as the High Range. There are noteworthy patches that appear in a similar manner located at slightly lower altitudes. These areas, such as the Brahmagiris and Kudremukh in Karnataka, have the appearance of a shola system. The structure (higher forest canopy) and composition (different species of plants) of these areas are distinct from the higher, more typical shola systems. Curiously, Sri Lanka has near identical habitat in the patanas (grasslands) and the cloud forests of its Central Highlands. These bear remarkable similarity to the sholas of south India, but for one conspicuous difference; in Sri Lanka, the cloud forests grow on exposed ridges and hill tops while the valleys have patanas, the reverse of what is found in the shola of the Western Ghats!

The shola-grasslands mosaic is typically found on high plateaus composed of gentle, undulating hills. The grasslands occupy a larger proportion of the area (80 per cent) of the upper plateaus than sholas. Rainfall over the Southern Ghats is high and can vary from 1,200 to 5,000 mm. depending on proximity to the western coast where the southwestern monsoon makes landfall in the summer months.

Higher altitudes mean colder temperatures and in many of the ranges the temperature drops below freezing point in the winter months. Frost is a common feature in the grasslands from December to February. The sholas, with their canopy of evergreen vegetation, are able to maintain more constant temperatures throughout the year. While grasslands can tolerate severe frost, there is unlikely to be any in a neighbouring shola. This is important for regeneration since shola saplings cannot survive winter frost. Grasses, on the other hand, will die above the surface level while root structures are able to survive frost, grazing and even fire. One of the few tree species to be found in grasslands is the fire tolerant rhododendron Rhododendron nilgiricum.

A herd of Nilgiri tahr Hemitragus hylocrius near the Eravikulam National Park, which constitutes almost half of all the surviving habitats available to wild Nilgiri tahr.

Origins of grasslands

For many decades, the origin of these montane grasslands has been the subject of debate and controversy. Are they natural or man-made via the burning of forests? Given the enormity of floristic diversity and endemism, it is unfortunate that such a debate should have arisen. Even at the most basic intuitive level, it would seem obvious that such a finely-tuned complexity could not be a weedy by-product of a damaged ecosystem. Fortunately, recent pollen studies have shown them to be in existence for at least 40,000 BP (Before Present) in the Nilgiri Hills, long before influence from humans.

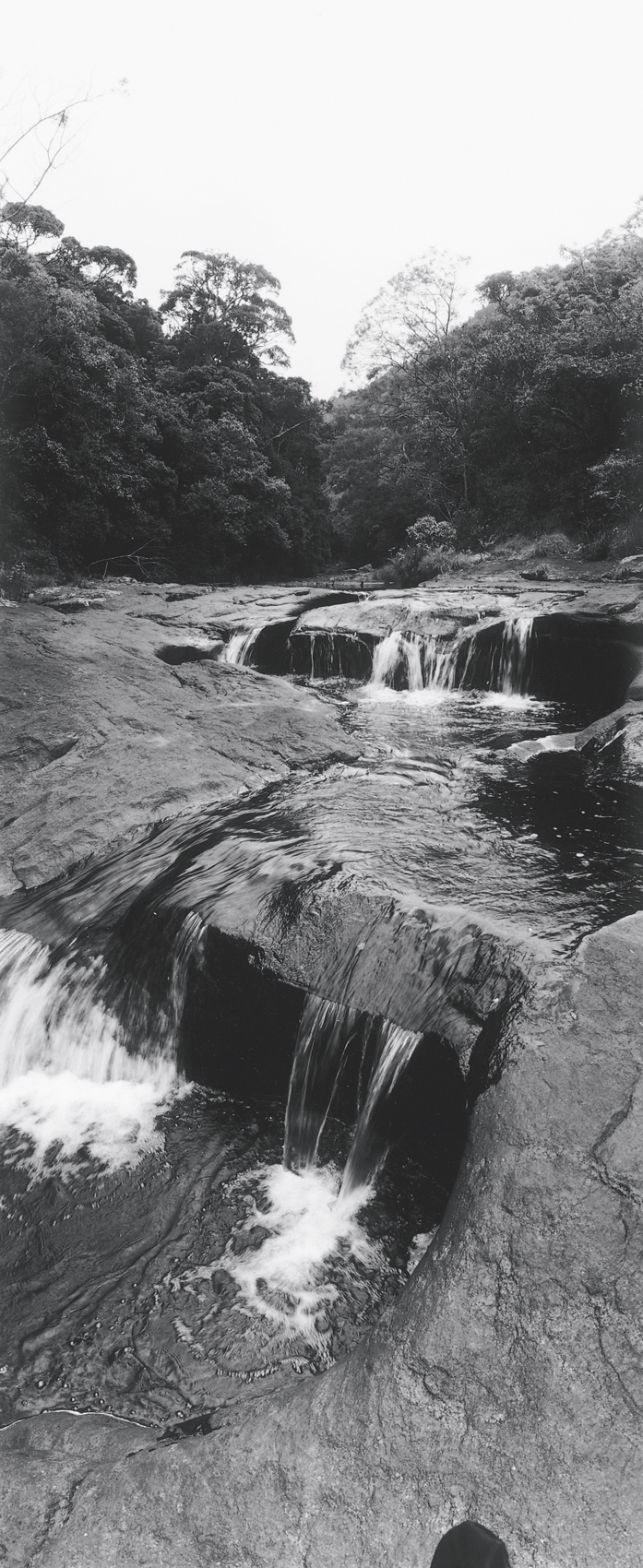

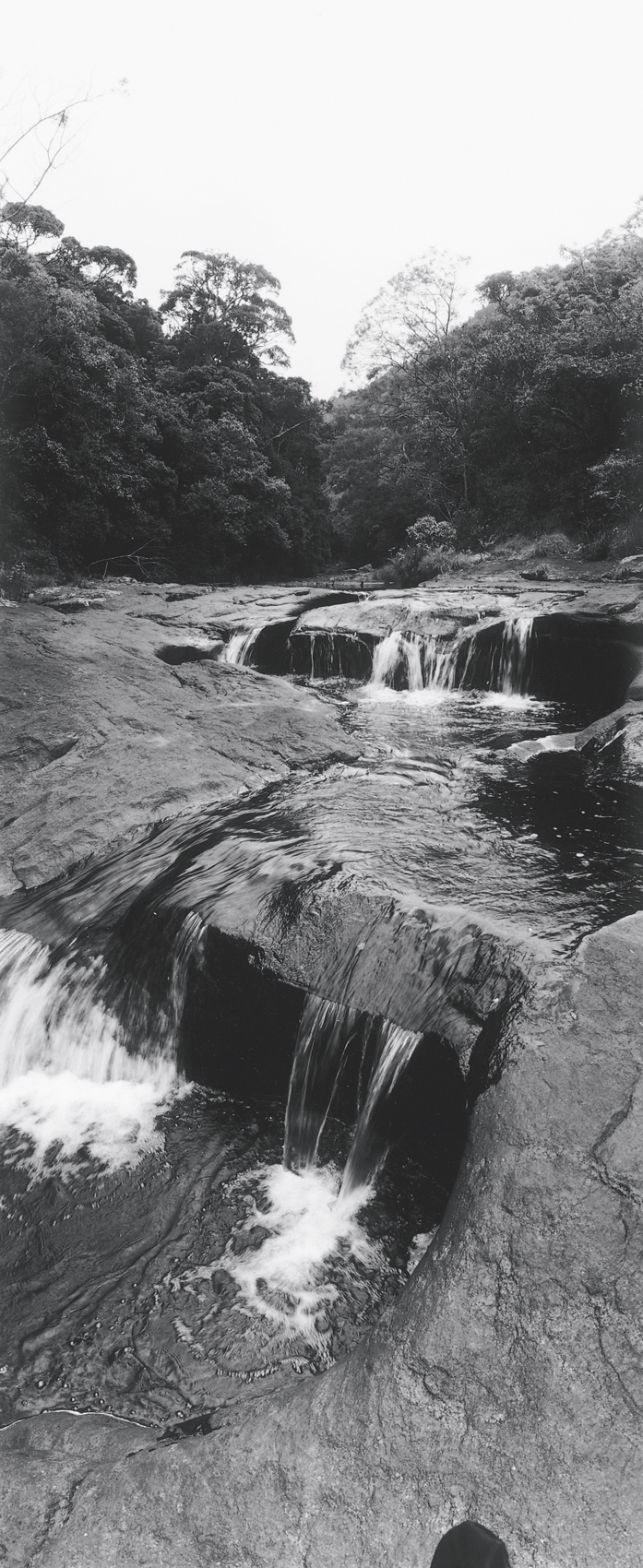

With native grasslands, the shola ecosystem absorbs the monsoon rains and subsequently supplies water to the plains through perennial sources such as the Gundar stream.

Ecological value and threats

Ecologists recognise several important traits in undisturbed shola-grassland systems. Firstly, they are now recognised as a unique system with fascinating linkages to similar montane systems in Sri Lanka and other tropical mountainous areas. Secondly, they have significant biodiversity that is not found elsewhere. Lastly and most importantly to humans who have never seen them, sholas provide water security for millions of people living in the shadow of the hills. The sholas act much like a giant sponge, absorbing monsoon rains and releasing them slowly through the year.

One of the most significant threats to grasslands has been their widespread conversion into monoculture plantations of non-native timber. Fast-growing species such as Eucalyptus globus, Pinus patula and Acacia mearnsii were intensively planted in almost all of the upper areas of the Western Ghats since colonial times. In recent decades, with afforestation gaining popularity in official circles, it was thought that the timber provided by these programmes would be worth any ecological costs. Biodiversity was not recognised as of any significant value in the un-notified areas of the upper Western Ghats.

Southern India’s highest peak, Anai Mudi dominates Eravikulam’s grassy hills and valleys. This stunning wind-swept area holds the best-protected shola-grasslands system left in the Western Ghats.

The conversion of grassland into plantations started during colonial times after many of the upper ranges were ‘discovered’ and developed into hill-stations and tea estates. Tree plantation expansion continued after Independence and several important hill areas (the western catchment of the Nilgiris) were severely damaged by hydroelectric schemes. In the 1960s and 70s, industrial demand on the plains (such as for tannin by the leather industry) helped encourage plantation expansion in many hill ranges. By the 1980s, very few of the elevated plateaus of the southern Western Ghats were untouched. The Nilgiris and Palni hills have lost almost all of their native grasslands to tree plantations. Thankfully, most tree plantations rarely cut into sholas and there are several important sholas left in these hill ranges, albeit surrounded by exotic plantations. A significant issue with several species (wattle and lantana) is that they self-seed and, unaided, spread into undisturbed areas. Other threats include illegal ganja plantations that cut into remote sholas. Eucalyptus oil distillation contaminates water sources. In some areas, there has been encroachment by tea estates and their use of pesticide and fertiliser is an ongoing concern. The rapid spread of hill stations away from traditional town centres now poses a significant threat in hill ranges where there are no official Protected Areas.

Significant surviving shola habitats are found in several locations. Mukkurthy National Park in the Kundas of the western Nilgiris retains tracts of shola-grasslands. It is a shadow of what was once the largest area of shola-grasslands in the Ghats, yet it contains fine examples of grasslands vegetation and is also home to Nilgiri tahr and other montane species. In the Palnis, there are notable patches at Kukkal, Vandaravu and even on the landmark Perumal Peak. A few isolated patches are left in the hills of Wayanad and Palghat. The High Range and the Anaimalai hills retain the largest undisturbed areas of montane grasslands. Most of this falls within Eravikulam National Park and the neighbouring Grasshills Protected Area (part of the Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary). This collectively totals to roughly 400 sq.km. of existent habitats, much of that threatened by invasion of non-native species.

A large tree fern Cyathea nilgirensis distinguished by its spiny rather than hairy branches, frames a stream in the Palni Hills.

Sholas

Sholas are tropical montane forests that are found in the valleys and folds of mountains. The word ‘shola’ is taken from the Tamil word sholai meaning any evergreen forest and the word has often been used to name lower forests areas (such as Karian Shola near Top Slip in the Anaimalais). It is now more correctly associated with the native forest of the lofty plateaus of the southern Western Ghats (above 1,700 m.). Like other montane forests in tropical areas, sholas usually experience high rainfall during seasonal rains. Cloud forests are able to derive moisture from wet mist when it is not actually raining and this may apply to some of the sholas in the Western Ghats. Their location in valleys provides better protection from monsoon winds and offers better soil conditions with higher moisture and nutrient content. Wind is an important factor and the canopy height of sholas is rarely above 15 m. (with some notable individual trees growing as high as 40–60 m.). Woody shrubs of the middle storey, such as Lasianthus and Psychotria species play an important part in sholas. There are a variety of Strobilanthes shrubs found in the understory of sholas (only a few species in the genus, such as kunthiana, are found in grasslands). Branches and trunks of undisturbed shola trees are gnarled and drip with copious amounts of mosses, lichens and epiphytic orchids. The crowns of shola trees often have a distinctive umbrella shape giving them the appearance of overgrown broccoli plants. The period of new foliage in spring heralds intense hues of red, pink through to bronze and bright green in the shola canopy.

Restoration efforts in the Palnis

An exciting development in the Western Ghats in recent years has been the initiation of several ecological restoration projects. This is a process where native vegetation is revived in an area damaged by anthropogenic activities including the introduction of non-native plants. Restoration projects have been started around the world in the last few decades but are relatively new to India. Ecologically speaking, restoration is the ‘next big thing.’

Ecological restoration initiatives in the Western Ghats are aimed at restoring native vegetation that has been wiped out or damaged by plantations and the spread of invasive alien species. An early success was started in Kodaikanal where the Palni Hills Conservation Council (PHCC) (see NGO Profile, Sanctuary Vol. XXV No. 3, June 2005) has established nurseries for shola species as well as different altitude plants since the 1980s. This wasn’t strictly speaking ‘restoration’ work but it did lay vital emphasis on indigenous vegetation. Their motto “the health of the hills is the wealth of the plains” draws an important linkage to the pernicious problem of water scarcity in India. The PHCC nurseries have borne fruit and now there is good headway at getting these slow-growing trees re-established in the Palnis and neighbouring ranges. Another important effort is that of the Nature Conservation Foundation in the Anaimalais. Its aim is to restore rainforest habitat and forest corridors for wildlife in degraded tea estates in the Valparai plateau. Up until recently, no one had tried to restore the native montane grasslands of the Western Ghats, a reflection, perhaps, of the general lack of understanding of their importance.

Sholas may be small clumps or larger expansive forests that support trees that can grow to four or five metres, as seen here along the Eravikulam stream.

Just outside of Kodaikanal’s township limits, a bumpy road winds through Pambar Shola to the popular hiking spot of Dolphin’s Nose. It is here, in a former pear grove overlooking the southern escarpment of the Palni Hills, where grasslands restoration is being pioneered by the Vattakanal Conservation Trust. Their modest-sized plot is cluttered with shola saplings, tree ferns, potted orchids and numerous plants from the Palnis. The genius behind this small organisation lies in Bob Stewart and Tanya Balcar, British transplants who settled in Vattakanal and have spent the best years of their lives trying to save sholas and now grasslands. They are disciples of Fr. K.M. Matthew, the late botanical authority who penned the major botanical texts of southern India and was also a leading light at the PHCC (see Sanctuary Vol. XXIV No. 3, June 2004 for his obituary). Father Matthew was for long the director of the Anglade Institute of Natural History at Shembaganur, once a nucleus of botanical exploration across southern India.

The Vattakanal Conservation Trust (VCT) nursery was started in the late 1980s to provide fuel, fodder and utility alternatives to the local communities living around Vattakanal who were cutting wood in Pambar Shola. Over the years, they have evolved into a leading proponent of ecological restoration in the Palnis and Nilgiris. The Trust has been active in involving local residents in the restoration of Pambar Shola and they have planted thousands of saplings in and around the shola in the last decade and a half. In 2001, they collaborated with the Tamil Nadu Forest Department, a notable success for NGO and government cooperation. Walking down to Dolphin’s Nose, their fenced-off areas and the healthy saplings making a strong comeback are obvious. In recent years, the Trust has done botanical surveys in the hills and now has the most comprehensive catalogue of the plants of the Palni Hills. These activities have led to several important botanical discoveries, most notably the rediscovery of Elaeocarpus blascoi, a rare shola tree until recently thought to be extinct. The Trust has successfully raised E. blascoi as well as a host of other rare and endangered species. Many of these have been successfully reintroduced into the wild.

Birds And Other Creatures OF The Shola-Grasslands

Nilgiri Flycatcher

Nilgiri Flycatcher

Most of the endemic birdlife of the upper Western Ghats plateaus are found in the shola interiors rather than the grasslands. The Black-and-orange Flycatcher

Ficedula nigrorufa, White-bellied Blue Robin

Myiomela albiventis, Nilgiri Flycatcher

Eumyias albicaudata, Nilgiri Wood Pigeon

Columba elphinstonii and Grey-breasted Laughing Thrush

Garrulax jerdoni and Nilgiri Laughing Thrush

Garrulax cachinnans are all

shola species. The rare Broad-tailed Grassbird

Schoenicola platyura is found at lower elevation grasslands and not in the montane grasslands. The endemic Nilgiri Pipits

Anthus nilghiriensis is exclusively a montane grasslands bird. There are a whole group of snakes, the shieldtails, which are almost entirely confined to the Western Ghats and hills of Sri Lanka. Several of these are exclusively

shola species. Mammals endemic to the

Western Ghats include the Nilgiri marten

Martes gwatkinsi, Nilgiri langur

Trachypithecus johnii, dusky squirrel

Funambulus sublineatus are also found here. Nilgiri tahr prefer grassy habitats with a clear field of view. They will only enter

sholas when appropriate cliffs are unavailable to them.

The idea of restoring grasslands is linked to the blooming of kurinji, a shrub that flowers in montane grasslands only once every 12 years. For over 10 years, there has been a PHCC-sponsored proposal to protect the Palni Hills as a wildlife sanctuary, which has unfortunately been held up by various roadblocks. A less ambitious dream of Father Matthew’s was to protect a hillside of native grasslands between Pambar Shola and the popular Coaker’s Walk. The area suffers from invasions of lantana and wattle. Amidst these alien species are significant patches of the original grasslands. The 19th century-surveyor Douglas Hamilton recounts hunting the “old buck (tahr) of Kodaikanal” here in his book A Record of Sport in Southern India (1892). The VCT has proposed to restore grasslands in this area including the badly-degraded hillside below Coaker’s Walk. During years like 2006, this would be an ideal kurinji habitat. This restoration is seen as a precursor for further and more extensive restoration efforts in the outer hills.

The proposal to restore grasslands calls for several steps to be taken. First permission needs to be obtained to clear degraded land. This can be tricky since the clearing often requires that invasive trees are culled or harvested. With so many legal roadblocks in place to prevent deforestation, this is a formidable barrier to a successful restoration project. It might also explain why restoration projects have often been unpalatable to the Forest Department. Once permission has been granted, the area has to be cleared of invasive species. This is a time-consuming and labour-intensive operation since the invasives need to be removed from the roots in degraded grasslands. The application of herbicide to cut stems or de-bark is another option of removing invasives, but this has its own problems. The soil has to be prepared so that grass species can be transferred in. These would initially have to be grown in a nursery. Seedlings need to be transferred at a time when there is adequate moisture (monsoon) and no frost. Then the area needs to be carefully monitored over the coming seasons. It is a significant challenge in a small area such as the Coaker’s Walk hillside and a seriously-daunting task if one is to try to reverse the invasives in the expansive pine or eucalyptus plantations in the upper Palnis.

Under the shadow of the Anai Mudi, or Inaccessible Valley is the Kukkal Shola of the Palni Hills, as fine an example of a shola-grassland ecosystem as one might ask for. A Reserve Forest, it does not enjoy the same level of protection as wildlife sanctuaries and national parks.

When I was most recently at the Vattakanal Conservation Trust’s new nursery in Pambarpuram, Bob and Tanya very excitedly bent over trayfuls of native grasses that they were preparing for reintroduction. They had so many samples that they had extended into their house’s lawn. Sacks of kurinji plants lined the pathway leading to their house and the evidence that they have all the raw material for grasslands restoration was evident. They now have some 300 shola margin species in cultivation here, of which 200 would be core species for grassland restoration. At the time they were waiting for the green light to start clearing and planting below Coaker’s. As this article went to press there were still bureaucratic hiccups that have held up the proposed kurinji sanctuary in Kodaikanal and one can only hope that the project will be initiated.

In February this year, the Forest Department formulated a policy to restore, over a 20-year period, the grasslands of the Mukurti National Park. This is an enormous task, but for those who have for decades cherished the dream of reversing the damage that has been done it is a task that will be relished.

Villagers are supposed to take their fuelwood from plantations, but, as this image reveals, pressure on the slow-growing shola forests continues. The three women seen here will probably plant potatoes on the land shorn of vegetation.

Back on Anai Mudi, the mist is starting to roll over the slopes and the lower hills are obscured in milky clouds. After several hours on this venerated peak it is time to go down and log in our observations. The hills are alive with new kurinji plants and it is exhilarating to imagine what they will look like during the upcoming flowering. It is reassuring that Eravikulam is a secure shola habitat and a critical Protected Area hosting several endangered species. Just across the hills in the Palnis, the experiments of restoring grasslands hold a great promise that some of the past century’s ecological destruction can be reversed. It’s a promise that holds important lessons for other degraded habitats in the Western Ghats and across India’s diverse land.

For more information about the author’s work, go to http://www.highrangephotography.com

Kurinji Flowering

Kurinji

Kurinji

The

neelakurinji or

kurinji plant

Strobilanthes kunthiana is a unique species of shrub that blooms in the high altitude hills of the Western Ghats every 12 years. It bloomed in 1982, 1994 and is now expected during the 2006 spring and monsoon. The

kurinji plant is associated with the

shola ecosystem and is a unique botanical feature of the southern Western Ghats. During the years that it blooms, whole hillsides of native grasslands are covered in the mauve colours of the flower. The peak blooming usually happens at the height of the Southwest monsoon (July-September). Some historians associate the name of the Nilgiris (literally ‘blue hills’) with the blooming of the

kurinji flower. The

Todas of the Nilgiris revered the flower and were aware of its lifecycle. Honey hunters know that

kurinji flowering years produce an excellent honey that is much sought after by connoisseurs. Excellent flowerings can be expected this year in Tamil Nadu’s Anaimalai and Palni Hills as well as the High Range of Kerala. The Nilgiris flowered last year and thus it will be another 11 years before they bloom again. This year’s blooming will be a good indicator for remnant grasslands and should help ecologists gauge the extent and health of montane grasslands in the Western Ghats.

Evolving Picture By Bob Stewart

Bob Stewart and Tanya Balcar

Bob Stewart and Tanya Balcar

Decades after the mass planting of exotics in the Palni grasslands, the two long-term consequences are becoming increasingly apparent. The first has major implications for water security. Everywhere on the plateau, marshes are shrinking or have dried out completely. These are the source of countless streamlets, which ultimately provide power and irrigation for hundreds of thousands on the plains. Even the famous Berijam lake and marsh are visibly shrinking. It is not only the plantations’ propensity to intercept groundwater that contributes to this shrinkage. Thousands of tonnes of plantation debris clog the catchment. Fast-growing wattle is especially vulnerable to toppling over, unable to support its own weight, the exposed roots creating thousands of points of soil erosion. Ironically, wattle is the first casualty in the competition for depleted ground water. The great die-off and die-back began in the last year and has accelerated post monsoon in 2006. In the past year, crores have been spent in the Upper Palnis raising check dams across marshes and streamlets. These can provide some temporary respite but only a long-term strategy of restoring some semblance of the original grasslands can bring about a significant recovery of the water regime.

The second long-term consequence is far less alarming; that is the spread of shola forest species into the plantations. This is so advanced in places that some observers think, wrongly, that the plantation is invading the shola. In one instance, on the slopes above Blackburn marsh, what remains of an old wattle plantation is being rapidly eaten up by shola, with even rare orchids, such as Chrysoglossum maculatum, joining in the feast!

Given these dynamics, a practical approach to landscape management here would focus on remnant grassland maintenance and restoration, whilst encouraging the millions of emerging shola saplings in the direction of a full blown

shola forest. Such a strategy would restore water security and conserve and augment biodiversity. There would still be room for the raising of

shola tree nurseries, but they should be instrumental in restoring existing ruined and degraded

sholas rather than for the random planting that is the ongoing policy.