New Eyes in a Dark Forest

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 28

No. 12,

December 2008

By Rohit Naniwadekar and M.O. Anand

Back-of-beyond Arunachal Pradesh! We had heard so much about the magic and rich biodiversity of this land that when we got a chance to be part of an expedition to Namdapha, we did not think twice about accepting! Having worked in the Western Ghats, we were quite familiar with rainforests, but what instantly struck us about Namdapha was the sheer extent, the seeming endless nature of the wilderness.

We were in Namdapha to coordinate and conduct a camera-trapping survey of this reserves rich, yet elusive mammal community. This was to be part of a long-term conservation programme of the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), led by Aparajita Datta. At least once every year, since 2002, Aparajita has taken a long walk, clambering over rocks, wading through slush and crossing rivers and landslides to reach Gandhigram to the east of Namdapha. Gandhigram is home to 230 Lisu families, a tribe with their origins in Myanmar. Aparajita leads a project that actively engages with the Lisu, promoting education, healthcare and development in the hope that progress on these fronts will reduce the Lisus cultural and economic dependence on the forests of Namdapha, particularly that of hunting.

The NCF's conservation programme in Namdapha National Park has been in place for close to five years now. A key component of the project is to monitor trends in wildlife species and communities, as an index of the efficacy of the conservation programme. However, inaccessibility and the associated logistical difficulties are major impediments to conducting scientific studies in what may well be the most biodiverse Protected Area in the country. Scientific wildlife studies in Namdapha have consequently been largely limited to exploratory surveys. We know, to some extent, what is to be found in this remarkable place, but little about the current population status of species, trends in their population or the full measure of the threats they face.

One of the key components of the Nature Conservation Foundation’s long-term study at Namdapha is measuring population trends of wildlife species using camera traps to estimate the effectiveness of their conservation efforts. Seen here is a Grey Peacock Pheasant Photo: Namdapha Wildlife Monitoring Programme, NCF.

Our Expedition

Our goal in the winter of 2006 was to conduct a camera-trapping survey across the lowland forests of Namdapha National Park. Between November 2006 and January 2007, we walked close to 400 km. and deployed over 100 camera traps at various locations along stream beds, animal trails and ridgelines within the national park. Our target species were mammals ranging from tigers, clouded leopards and gaur to mongooses, civets and porcupines. This effort, we believed, would give us sufficient data to make a preliminary assessment of the status of large mammal populations in the park and would serve as a baseline for future monitoring.

The NCF's field coordinator in Namdapha, Akhi Nathany, had assembled a team of Lisus who were to be our lifeline through the expedition. The Lisus are unmatched in their knowledge of the ways of the forest. They run a simple, yet highly-efficient camp. Most importantly, they are great company in the field. It was their spirit, kindness, lively sense of humour and all those Lisu songs we sang at the camps every evening that helped us all pull through some of our toughest moments.

The task ahead of us was daunting. The constraints of our study design were such that we could not deploy the cameras simply wherever we pleased or found convenient. Instead, a randomly-generated selection from a computer programme had located these sites, few mercifully close to trails and good campsites, but many others in far away valleys separated by rugged mountains, powerful rivers, swamps and forests of dense and thorny cane.

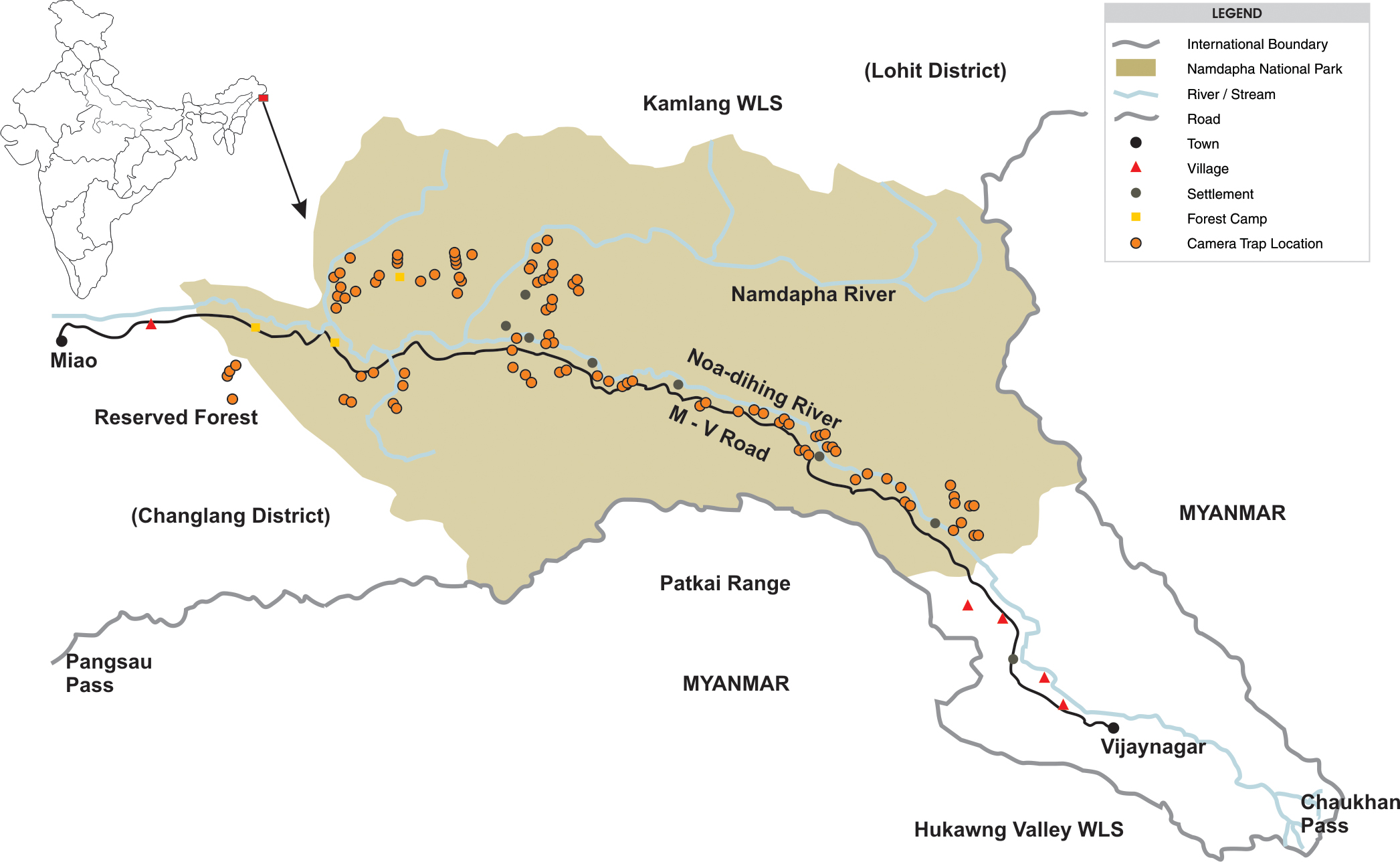

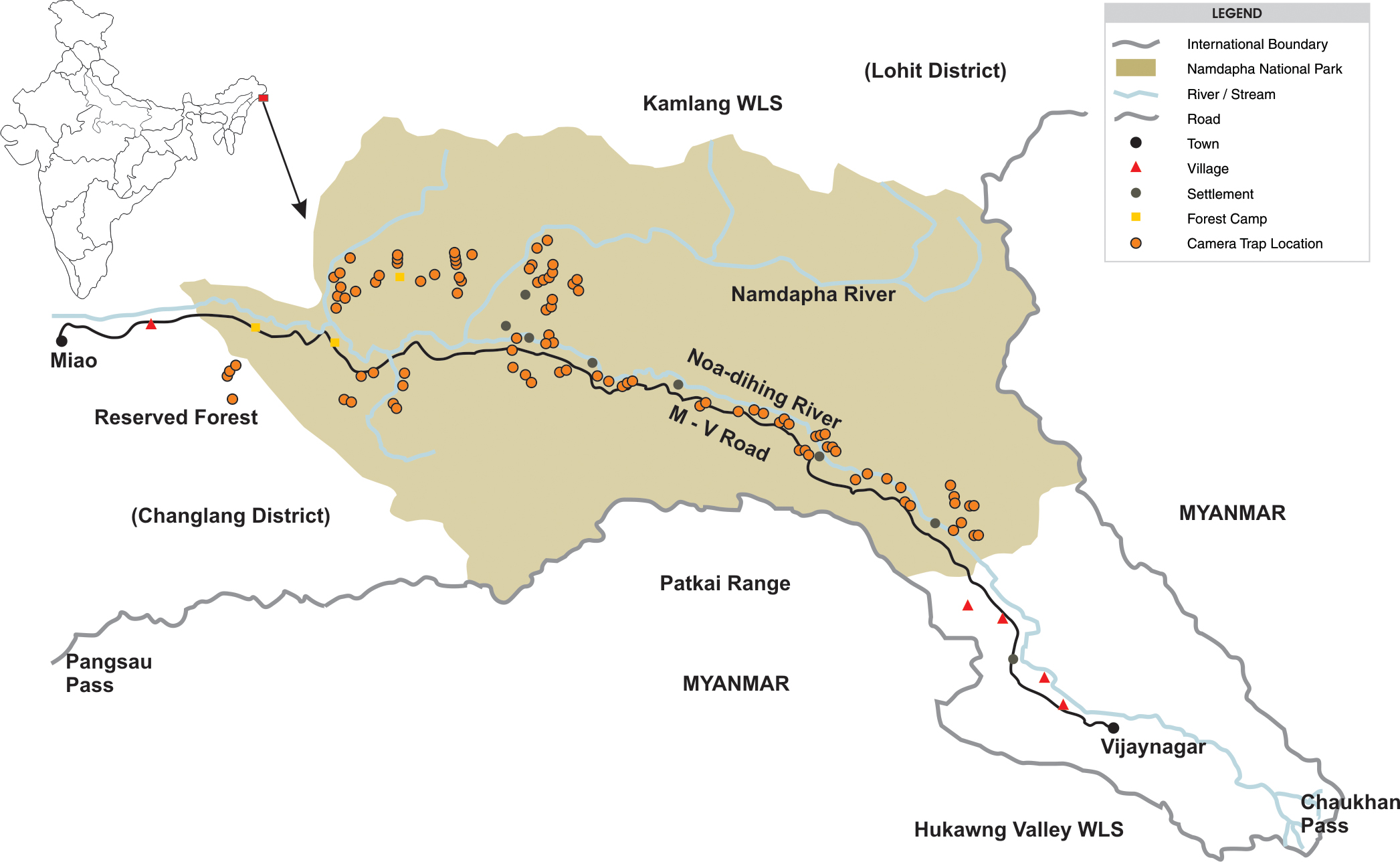

Locations of camera traps placed.

The expedition began in the town of Miao, on the banks of the Noa-Dihing river to the west of Namdapha National Park. From here, we planned to work our way up the Noa-Dihing valley, along the erstwhile Miao-Vijaynagar (MV) Road. The road passes two Lisu settlements within the park, then onto Gandhigram, ending at Vijaynagar along Indias border with Myanmar. The 150 km.-long road, which follows the course of the Noa-Dihing was motorable for just 26 km. From along this road, we planned to branch off, up the valleys of tributaries, along footpaths or game trails.

Since we had planned to survey most of the lowland forest stretch of Namdapha, it involved continuously moving from one camp to another. The food we ate was simple yet delicious - smoked domestic pork with rice and chutney was our staple. Now and then we got replenishments from the settlements in the form of eggs and vegetables. After a quick meal, by around seven a.m., we would set off in two teams to deploy our camera traps. Lisus, some of them erstwhile hunters, have tremendous experience in identifying trails regularly used by animals. Their knowledge of the area helped them enter trails to seemingly inaccessible areas and to places we would just point to on our maps. After a normal day, which involved deploying traps and sampling basic vegetation, tracks and pellet plots to locate ungulates like the barking deer, wild pig, sambar and gaur, we would invariably have a few games of chilo (a local version of the Thai sport Sapak Tragor) along with lots of lacha (local tea) followed by an early dinner. Chilo is a cross between volleyball and football where feet and head are used to get the ball to the other side of the net.

The research team braved inaccessible terrain, inclement weather and vast distances to set up over 100 camera traps targeting large mammals such as the clouded leopard (top), tiger, gaur and sun bear. Photo: Pg 29B Namdapha Wildlife Monitoring Programme, NCF.

The Namdapha Experience

In Namdapha, unlike many of India's drier Protected Areas, animal encounters are infrequent. Dense vegetation results in poor detection of animals and years of hunting have probably led to behavioural changes, making animals extremely elusive and shy. In such a scenario, camera trapping is acknowledged to be an effective technique for conducting mammal inventories. Camera traps are now extensively used for species inventories, studying the activity patterns of animals and in some cases even estimating densities of animals wherein individuals can be differentiated. Our camera traps, unlike the other type that essentially detect motion, had infrared sensors capable of detecting the body heat of animals, which triggered the cameras.

The survey took us to some truly remarkable places and showed us Namdapha like few outsiders have ever seen it. We explored verdant rainforests on the Hornbill Plateau and the wide open grasslands of the Namdapha river valley at Firmbase. We watched in amazement as the morning mist lifted from Firmbase to reveal the lofty Dapha-Bum in all its snow-covered grandeur. We climbed up the courses of small mountain streams, which opened up into pristine hilltop forests, where we often saw hoolock gibbons, capped langurs and hornbills. Perched precariously at Anga-chu - the takin salt lick - we marvelled at how this buffalo-sized mountain ungulate managed to hold its own on the steep cliffs and crumbling boulders that are its home. We will never forget the sightings: mixed hunting flocks (for more on the phenomenon, check out page 46) of over a 100 birds with rare species such as the Snowy-browed Babbler among them. Our sightings also included a Hogdsons Frogmouth perched motionless for hours in a bamboo thicket, White-tailed Eagles and White-bellied Herons along the Noa-Dihing river, Medo pit vipers hibernating in the hollow of bamboo stems and a false cobra with its incredibly colourful display. Namdapha is the kind of place where breathtaking scenery, once-in-a-lifetime sightings and unforgettable experiences are all par for the course.

Time passed quickly. Too quickly. Soon we found ourselves on the banks of the Lashichilo river, roughly the 80th mile along the M. V. Road. The river marks the eastern boundary of the national park. To us, crossing the river also meant the end of our survey, the end of carefree wandering and evenings under the stars; the end of a lifestyle we had grown to love. We walked for two more hours that day to reach Gandhigram, the Lisu village. Here we stayed for over two weeks, waiting for the last of our cameras to be retrieved from the field. It was a welcome break, spent feasting on pineapples, sugarcane and zakhulu - a local variety of bread - recuperating from the exertion of the last few months and preparing for the long walk back to Miao.

The camera traps captured many other interesting species too, including the yellow-throated marten.

The Results

Months later, back in the big city, the film rolls from our camera traps started to tell their own incredible story. A few stunning pictures, such as those of clouded leopard, marbled cat, golden cat and ferret badger pointed to the incredible faunal wealth in Namdapha. But our data also revealed that these animals were being encountered at extremely low densities. Equally disturbing was the low density of large ungulates such as sambar, wild pig and gaur. Probably the most saddening was the fact that three months of camera trapping and walking had given us no evidence to believe that there were any tigers left in Namdaphas rainforests. This species, like most others, has probably fallen victim to hunting by local tribes in the pay of international syndicates. To put our results in perspective, the rate of encounter of most mammal species in Namdapha was far lower than in most other Protected Areas in the rainforests of Southeast Asia.

Hunting is a serious threat to wildlife in Namdapha, but at present it may be the only major one. For miles and miles beyond Namdaphas borders, the forest extends unbroken, into the mountains of Arunachal Pradesh and the undulating hills and valleys of Myanmar. Given half a chance, wildlife populations including tigers can certainly make a strong comeback in Namdapha.

Making conservation work will, however, require innovative and maybe unconventional approaches that go beyond just the allocation of resources and patrolling of the park by armed guards. The solution in all likelihood lies in the hands of the community that most affects the park: the Lisu. Support from the Lisu, however, may be difficult to come by because of the wide suite of problems that the community already faces. For one, their villages are currently landlocked between Myanmar on three sides and the Namdapha National Park. A long-term solution is urgently required to find adequate cultivable land outside the park for the increasing population of Lisus.

There is also an urgent need to find suitable job opportunities for the Lisus, some of which could be closely tied to Namdapha, for instance, sustainable wildlife tourism. Currently, they are deprived of the most basic amenities that most villages in the country enjoy - connection to major towns for access to avail of basic infrastructural, medical and educational facilities. This lack of connectivity to the outside world has also hampered Lisu enterprise, such as cultivating and marketing their local produce, including guavas, oranges, pineapples, thaja (Chinese apples or persimmon), cardamom and smoked pork, apart from a variety of handicrafts intricately woven from cane and bamboo. Streamlining their lives into the broader socio-economic framework would help reduce their dependency on Namdapha. The results of our survey may paint a bleak picture, but our resolve to bring about positive change through sensible conservation programmes burns even more fiercely.

When Aparajita takes the long walk again in the future, she will do so with a new team, and new ideas. The going may be tough, but these magical forests and high mountains are certainly magnetic and worth every effort. On a personal note, there are but a few experiences in life that remain indelibly etched in one's mind; our wanderings in the endless rainforests of eastern Arunachal Pradesh certainly have their place in ours.