Mountain Transitions

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 10,

October 2021

Text, Photographs and Map by Ian Lockwood

Recognition, Challenge, Change, and Restoration in the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

10.3 Degrees North, 71.3 East or thereabouts and I’m on foot in the heart of the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot. I am on a pilgrimage, a small chapter in a learning excursion that has now stretched several decades. I carry an explorer’s tools – cameras, binoculars, maps, a notebook and GPS. But this is really a journey of the spirit. By happy coincidence, I had first visited this serene mountain as an 11-year-old on a family camping trip in the spring of 1981, the year that Sanctuary first went to press.

Earlier, in the chilly winter darkness of the morning, a small group of us had navigated the dense thicket of a large shola to emerge on a grassy, exposed escarpment of montane grassland. Now the sun has risen over the azure ridges of the eastern Palani hills. We seem to be the only humans in this little-known corner of the Western Ghats and no concrete, steel or alien wood blemishes the immediate scenery. I am accompanied by my good friend, the talented photographer Prasenjeet Yadav who is documenting the emerging idea of ‘sky islands’. My son Lenny, the fourth generation in our Indo-American family to be privileged to walk these hills, trudges alongside. It will be him and future generations that will take on the mantle of conservation in a warmer, more crowded world defined by uncertainty.

A Nilgiri Pipit Anthus nilghiriensis is flittering in the grass next to a gnarled Rhododendron tree adorned by a flush of its crimson flowers. The bird’s drab colours do not stand out but its very presence is a strong indicator of a healthy shola grassland. Further up the ridge a modest Shaivite shrine crowns the weathered summit and cliff edge. Amongst tufts of grass overlooking a precipitous drop is a set of miniature swings – a quirky human addition. The cut granite posts of the swing are covered in lichens, and merge with the landscape. As we navigate a series of dizzying steps up the cliffside, a small herd of Nilgiri tahr scampers down the slope.

When I first started coming here as a child, these emblematic, endemic species were impossible to see. Poaching had drastically reduced tahr numbers across their southern Western Ghats range. Now, tahr seem to be making a slow, cautious recovery, according to a study by WWF-India in 2015. Further down the ridge, into an area that is now protected as the Anamalai Tiger Reserve, I have encountered or seen evidence of large fauna including gaur, elephants and tigers. In a land with such a long, rich history of human interaction with nature, it is remarkable that such megafauna survive here in this Indian sky island.

_C-1700_1633600636.jpg)

Key species from the Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot collage (Row 1): Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni, Black-and-orange Flycatcher Ficedula nigrorufa, purple-faced langur Semnopithecus vetulus, Jayram’s bush frog Raorchestes jayarami. (Row 2) Gaur Bos gaurus, large-scaled pit viper Trimeresurus macrolepis, kurinji Strobilanthes kunthiana. (Row 3) Nilgiri tahr Nilgiritragus hylocrius, damselfly Neurobasis chinensisat, Sri Lankan leopard Panthera pardus kotiya, lyre-nosed (or hump-nosed) lizard Lyriocephalus scutatus. (Row 4) Horsfield’s spiny lizard Salea horsfieldii, lion-tailed macaque Macaca silensus, daffodil orchid Ipsea speciosa.

Across a sea of mist that obscures an expansive valley, we can see Anai Mudi in all her rugged majesty. This is the High Range and amongst the peaks are the tallest, least-disturbed reaches of the Western Ghats. The rolling plateau of Eravikulam and Anamalai Hills are a high rampart protected by vertical granite faces. Out of our field of vision, they taper down to Kerala with rainforest-cloaked hills, valleys of plantations and hydroelectric reservoirs. To the northwest, across the Palghat gap I can make out the broad blue profile of the Nilgiris Hills. On its flank lies Silent Valley, home to one of India’s most notable and successful citizen-driven conservation success stories. From the Nilgiri Hills, the Western Ghats stretch northward through Karnataka’s coastal zone to Goa. The Sahyadris (see Sanctuary Asia, Vol. 25, No. 3, June 2005) continue northward and parallel to the Konkan coast through the Deccan traps of Maharashtra and eventually conclude just over the Gujarat border in the Dangs. In the completely opposite direction, somewhere beyond the plantation-dominated plateau of the Palani Hills and across the Palk straits is Sri Lanka, a vital part of the hotspot and the place I call home.

RECOGNITION

Four decades ago, when this publication was in its infancy, the Western Ghats were little more than a geographic blip on the map of India. Protected Areas (PAs) such as Periyar, Mudumalai and Nagarahole had national recognition but there was little appreciation for the entire range as a complex interconnected landscape. In Sri Lanka, wildlife efforts were focused on large PAs like Yala, while Sinharaja and its highland ecosystems were only just starting to be appreciated. In both countries, key species, especially amphibians, were yet to be discovered or appreciated.

This started to change when efforts on a global scale to address biodiversity loss helped to galvanise and pull together threads and different players to protect what became known as a “biodiversity hotspot” at a sub-continental scale. The very notion of “biodiversity,” coined by Thomas Lovejoy and popularised by E.O. Wilson, only entered our lexicon in the 1980s. Its popularity and utility quickly grew. The Convention on Biological Diversity was signed at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio De Janeiro. Eight years later, the idea of the “biodiversity hotspot” was put forth by Norman Meyers and other authors in the landmark Nature article that proposed the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka as one of 25 original biodiversity hotspots. Conservation International, the New York-based civil society organisation, led efforts to draw attention to and support conservation efforts in the different hotspots. Sanctuary, with my lead article and photo essay, reported on the Western Ghats in April 2001 (see Sanctuary Asia, Vol. 21, No. 2, April 2001).

Sri Lanka and the Western Ghats were lumped together because of shared species and broad biogeographic similarities. The close association is not novel and had first been noted by the father of biogeography Alfred Russel Wallace in the 19th century. Some emblematic species, in spite of their location-specific names, are found in both parts of the hotspot, such as the Malabar Trogon Harpactes fasciatus and Sri Lanka Frogmouth Batrachostomus moniliger. In other cases, such as that of the Semnopithecus genus, each part of the hotspot has its own species. The southern Western Ghats has the Nilgiri langur S. johnii while Sri Lanka has the purple-faced langur S. vetulus (this has now been split into a number of different species). At the same time, the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka have species that are unique to their respective areas. The Nilgiri tahr, Nilgiri marten and purple frog are found in the Western Ghats. Sri Lanka has the marbled rock frog, lyre-nosed lizard, the Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni and a variety of species unique to its island boundary.

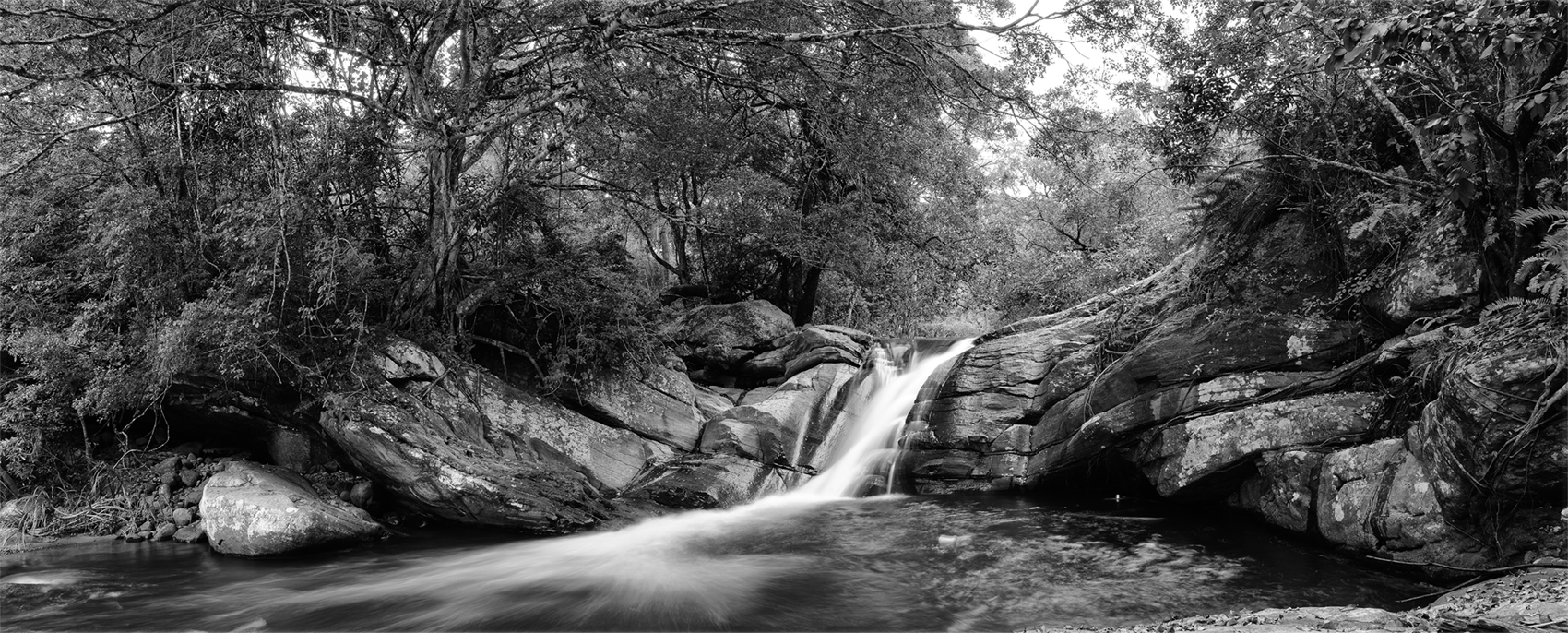

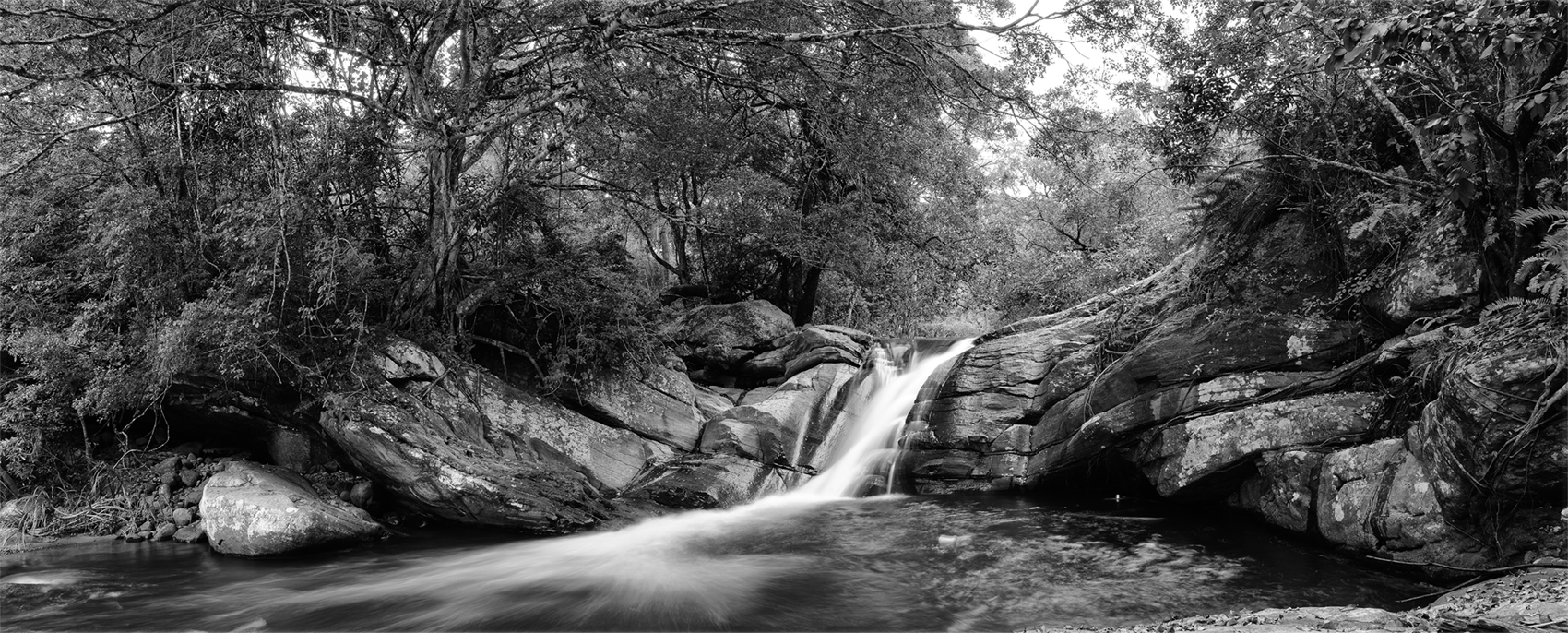

Water is a critical ecosystem service provided by the natural habitats of the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka’s Central Highlands. This waterfall is located near Belihul Oya in southern Sri Lanka.

Having lived in or visited much of the hotspot, I appreciate the differences as one transitions from the northern tip at Tapi river to Kanyakumari and across to Sri Lanka. Geologically speaking, the volcanic Sahyadris or northern Western Ghats and the associated Deccan traps are considerably different than the low forest-clad hills of western Karnataka and Goa or the ancient granite ranges of the southern Western Ghats. They all share escarpment-like relief and a “step” like quality (that gave the “ghats” their name). The entire range plays a pivotal role in intercepting the southwest monsoon – a defining aspect of the range. Sri Lanka’s Central Highlands roughly share similarities in geology and vegetation with the southern Western Ghats. In fact, they can be considered as part of the same range divided only by a shallow strait and low plains. The Central Highlands also serve as a barrier that defines monsoon rain patterns on the island. The wet zone in the southwest has unique attributes and exceptional endemism from higher sustained rainfall patterns dating back to Gondwanaland.

Further strengthening the idea of the biodiversity hotspot in the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka, UNESCO has recognised 37 sites in India and several key areas in Sri Lanka (including Sinharaja and the Central Highlands) as World Heritage Sites. This recognition came in 2010 for the Central Highlands and 2015 for the Western Ghats. The designation is a source of pride and gives impetus to efforts by citizens in both countries to protect their fragile mountain heritage.

(04_15)_C-1700_1633601478.jpg)

The Western Ghats, like these ranges and valleys of the Anamalai Hills, have wild areas closely woven in with human landscapes.

CHALLENGE & CHANGE: MOUNTAINS OF RAIN, BASTIONS OF LIFE

Across the length and breadth of the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka, a variety of challenges threaten the fragile life and ecosystem services provided by this heterogenous biodiversity hotspot. Human population densities in or on the edges of the hotspot are amongst the highest of any of the 34 global hotspots. Millions of people (245 million was the estimate in a 2007 profile) depend on the watersheds in the mountains of the Western Ghats for their water needs. In an age of rapid climate change and unpredictable consequences, the ability of the Western Ghats and Central Highlands (in Sri Lanka) to provide water is one of the strongest anthropocentric arguments in support of conservation. The hills are veritable sponges, soaking up torrential monsoon rains where habitat is intact and releasing it to watershed and plains communities. It seems trite but the Palni Hills Conservation Council (PHCC) adage “the health of the hills is the wealth of the plains” rings true up and down this range.

Historically (in the last 150 years), the clearing of land for plantations of tea, coffee and spices caused much deforestation in the hotspot. Most of the High Range, Nilgiris and Central Highlands lost vital habitat to extensive plantations in the 19th and 20th centuries. PAs in the hotspot are often wedged into relatively inaccessible areas between plantations. Working with progressive plantation owners to protect key habitats, facilitate wildlife movement and restore degraded lands is now a key conservation strategy.

The development of large hydroelectric reservoirs for power generation is another threat. Several notable dams in the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka were built during colonial times and both countries accelerated building in the post-independence surge to industrialise. Dam building flooded valuable natural forest areas and opened up otherwise remote areas for development while at the same time providing relatively clean renewable energy and water for irrigation. There are very few significant rivers left in the hotspot that have not been dammed in one form or the other. In the 1980s, objections were raised to the Tehri and Narmada dams (in north and central India respectively). The Silent Valley campaign in Kerala, which eventually drew Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s support was a rare victory for conservation initiated at a grassroots level. The protectors of the forest cannot be complacent and battles continue to be waged. The Chalakudy river in the same state is under pressure from those that see nature as purely a resource to be harnessed for industrial development.

_C-1700_1633601760.jpg)

CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE The dramatic landscapes along the Tamil Nadu/Kerala border near Top Station illustrate a complex matrix of human and natural systems. The Sri Lanka Frogmouth and Malabar Trogon are both found across the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot. Pilgrims bathe at a waterfall in the southern “spa” of Coutrallam. The falls are nurtured by dense forests that are protected in the Kalakad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve. The White-bellied Blue Robin Sholicola albiventris is an endemic species associated with sholas in the southern Western Ghats. This exquisite shola tree Photinia integrefolia sp. sublanceolata, or devil’s kitchen set amidst the iconic Pillar Rocks of the Palani Hills was featured in past writing and photo essays on the Western Ghats. A lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus mother and child. This species is associated with evergreen and semi-evergreen rainforests and has been the charismatic poster species of conservation efforts to protect the Western Ghats. The Malabar flying frog Rhacophorus malabaricus is one of numerous amphibians associated with the diverse range of habitats in the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot.

Other issues in the Western Ghats are vexing and stubborn in refusing to go away in spite of evidence showing their ecological damage and unsustainability. Extractive industries in ores and minerals, often with state sponsorship, have challenged conservationists looking to protect key habitats and wildlife corridors. This year, plans to expand east-west transit (road and rail) routes cutting across the Ghats near Dandeli in Karnataka and Goa were controversially approved by the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), a group that is tasked with protecting India’s wildlife.

The problem posed by plantations of timber species replacing native flora is one that has only recently been appreciated in conservation circles (see Sanctuary Asia, Vol. 34, No. 8, August 2018). Some areas, like the Palani and Nilgiri hills, show positive tree cover increases in recent decades. But this has been mostly non-native timber plantations of Eucalyptus, Acacia and Pinus species that have not been shown to benefit native diversity and may have a negative impact on the hydrology of the hills. I have a personal interest in the issue and have had the opportunity to explore historic and contemporary satellite imagery to demonstrate these changes. Working with a group of Indian-based scientists, we have now shown that satellite imagery can help us tell the dramatic story of land cover change and that much of it has happened within our lifetimes.

_C-1700_1633602039.jpg)

In more modern times there has been rapid growth in hill stations and other settlements in the hotspot. In the last four decades, growing prosperity and consumer wealth in India’s large metro areas, as well as the development of better roads and the availability of vehicles has put unprecedented pressure on all townships in the hotspot. This has contributed to classic urban problems such as solid waste management, worsening air quality, and decreasing availability of water for the hill communities. There is an urgent need to have in place a different set of rules for hill development that protectors can use to ensure that hill stations don’t become extensions of cities.

Scientific Discovery in the Hotspot

Important scientific research has been conducted in the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot in the last few decades. The hotspot is now well documented at a variety of scales and there have been a steady stream of peer-reviewed articles published on the area’s biodiversity. The large numbers of new species discovered has been a point of pride in the hotspot. These are in fact too numerous to catalogue here but suffice to say that the last few decades have been an exhilarating period of discovery.

India has several world-class biodiversity research programmes at universities, as well as civil society groups that have conducted both field work and community outreach. State-led agencies like the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and the Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) provided a space for important studies. Venerable organisations like the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) have had a long focus on the Western Ghats. The Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE), established in 1996 in Bengaluru has facilitated and been a catalyst for important research in the Western Ghats. The Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), based in Mysuru but with a key field office in Valparai, has a dynamic award-winning team working on rainforest studies, restoration and human-elephant conflict mitigation.

The amphibian discoveries in both the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka in the last two decades have been remarkable in the sheer number of unrecorded species as well as splits. The amphibian rockstar

S.D. Biju and his team from the University of Delhi’s systematics lab have been at the forefront of this effort.

New developments with genetic sequencing has led to splits in species and new understanding of the role of biogeography of the Western Ghats. Robin Vijayan at the IISER at Tirupati has been leading efforts to study different species and aspects of the sky islands. Several of Robin’s students and colleagues have been leading important geospatial work studying vegetation and land cover changes in the Western Ghats using remotely sensed images. In Sri Lanka, scientists have worked for decades on studying rainforest ecology in Sinharaja. Nimal and Savitri Gunatilleke are leaders of research and collaboration in the fields of forest dynamics, biogeography and restoration. Rohan Pethiyagoda has been a leading voice in the Sri Lankan conservation scene who has helped us better understand the uniqueness of the island’s wet zone biodiversity. As in India, there has been a healthy spike in citizen scientists observing and documenting everything from frogs and dragonflies to birds and whales in the last decade. One of the most important discoveries here was that of the Serendib Scops Owl in 2001 by Deepal Warangal. The discovery of a South Asian bird species new to science has given us both excitement and hope for an uncertain future.

Hotspot Digital

The explosion of new digital tools and social media platforms has brought much of the hotspot’s biodiversity and protected areas into the public domain. Digital photography has allowed enthusiasts to record all varieties of life, from insects and amphibians to primates and large carnivores. Species that were only known from field guides based on musty specimens are now beautifully recorded and shared on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and other platforms. Annual gatherings like Nature in Focus have helped to highlight new talent and remind users of conservation messages. Conservation India highlights ongoing wildlife battles, challenges and success cases while reminding readers about the countless steps to being an ethical wildlife photographer. Many of the talented and successful Indian filmmakers and photographers who have focused on themes of conservation cut their teeth in the Western Ghats in the last four decades. Shekar Dattatri, Suresh Ellamon, Ashok Captain, Sandesh Kadur, Kalyan Varma, Ramki Srinivasan, Dhritiman Mukherjee, Prasenjeet Yadav and Rathika Ramasamy have all spent time in the Ghats and produced important work here.

RESTORATION & RESEARCH

One of the most important developments in the last few decades has been the initiation of ecological restoration movements in the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka hotspot (see Sanctuary Asia Vol. 36, No. 3 June 2005). These started as small-scale initiatives by individuals and civil society groups but the hope is that the basic approach and ideas will be adopted by state agencies. The idea behind both passive and active restoration is to understand site-specific ecosystems and then nurture and bring back key native species and whole ecosystems.

(01_19)_C-1700_1633602443.jpg)

Sunrise over the sky islands of the southern Western Ghats. Ecosystems in the higher reaches are distinctly different and unique from the lower plains, an idea that is being increasingly recognised and appreciated.

Efforts in the Palanis, Anamalai and Nilgiri Hills have shown promising results. There are shola nurseries in key locations in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, where people better understand the difficulty of bringing back these slow growing trees in the higher reaches of the ghats. The outstanding work of the Nature Conservation Foundation on the Valparai plateau to restore (lowland) rainforest fragments is notable for their grassroots efforts, scientific approach and success after two decades of collaborative work. The idea of restoring montane grasslands that was first trialed by Bob Stewart and Tanya Balcar of the Vattakanal Conservation Trust in Kodaikanal has now been followed up with a novel restoration programme outside of Ooty as well as by both the Kerala and Tamil Nadu Forest Departments. It remains to be seen if it is possible to restore shola/grassland mosaic systems. In Sri Lanka, efforts are underway to restore tea plantations that were formerly tropical rainforests. The UN has designated this as the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-30). Clearly, this is a field that we expect to see future advancements, courtesy of both state agencies and citizen initiatives.

Back on the grassy summit with its sweeping vistas, the sun is near its zenith and it is time to return. We’ve lost a little blood to leeches and are slightly sunburnt from the high UV levels of the open ridge. We have had a marvelous time looking for wildlife and appreciating the serenity of the Western Ghats wilderness but we’re ready for a good south Indian thali lunch. The views are not as sharp as when we first arrived and a haze has risen over the High Range. We pass a promontory with a view of the valley where my grandfather Edson composed a photograph in the 1920s. I marvel that this is one of the few places where little has changed in the last 100 years. It is a difficult place to leave but we do so knowing that there are people working to protect this landscape for future generations.

MANAGEMENT

In the Western Ghats, six states and their forest departments have jurisdiction over different parts of the Western Ghats while in Sri Lanka two main government ministries are the key players. India’s Central government has played a role in shaping policy with two detailed reports in the last 20 years. The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (The Gadgil Report) (2011) and Kasturirangan Commission (2013) both attempted to address the need to protect the hotspot. They both sought to notify key areas as “ecologically sensitive zones” (ESZs), a category with legal rights that would restrict further development. Pressure from politicians and individuals who felt that they might lose out made implementation of the reports difficult. To this day, the notification of ESZs remains unresolved.

A regular contributor to Sanctuary since 1996, Ian Lockwood has an enduring interest in the ecology, landscapes and cultural facets of South Asia. Further examples of his work can be found on his blog and website.

(04_15)_C-1920.jpg)

_C-1700_1633600636.jpg)

(04_15)_C-1700_1633601478.jpg)

_C-1700_1633601760.jpg)

_C-1700_1633602039.jpg)

(01_19)_C-1700_1633602443.jpg)