Meet S.Theodore Baskaran

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 2,

February 2021

A man of many parts, watchful guardian, memory-keeper and nature messenger for tomorrow, he was awarded Sanctuary’s Lifetime Service Award 2020 for propagating nature conservation all his life. He retired as Chief Postmaster General of Tamil Nadu and as a prolific author in Tamil, he brings conservation to people in their own language. A long-time association with WWF-India saw him serving two terms as a Trustee and he also served as the South India representative of the International Primate Protection League. At the young age of 81, he spoke with long-time friend Bittu Sahgal about his life, his passion for writing and constant effort to inspire the young to trust in and nurture nature.

Theodore, I love your moustache. Does it have a story?

Oh yes! It does. In 1996, I visited a farm near Rajkot, which had a prize Gir bull. My idea was to photograph it for a series of stamps on indigenous breeds of cattle. Vasa, a 72-year-old farmer, who had a strong athletic build, was in charge of the bull. I spent a day with him, saw him handle the animal, which was almost like a small elephant. I was so impressed that I wanted to pay a tribute to him. I started growing a moustache like his. But mine is not as glorious as his typical Saurashtrian moonch.

You were born in Dharapuram. But where did you grow up? Tell us a little about your family.

Yes, Dharapuram, a village by the river Amravati, which originates in the Palani ranges of the Western Ghats. On a clear, cloudless day, you can see the majestic ranges in the northern horizon. ‘Dharapuram’ means ‘the land of the immortals’. It has a perennial river named after Tara, the Buddhist Yakshini. In fact, there are nearly six places in India bearing that name, including Tarapur in Maharashtra. My parents were schoolteachers and we were poor. I shared my childhood with two sisters and two brothers and our parents gave us the freedom to choose who we wished to be, what we wanted to study. They were emancipated. Most of our time was spent outdoors by the river, swimming in the farm wells, and on trees. I wish children today could experience such a life. I remember once rescuing a jungle cat kitten from a well and hand-rearing it. Nature was part and parcel of our lives. We knew which snakes to avoid, and which birds and animals lived around us. That is how I developed a bond with the natural world. The night sky was full of stars and the milky way could clearly be seen. On moonlit nights, we played hide and seek. I had a wonderful childhood.

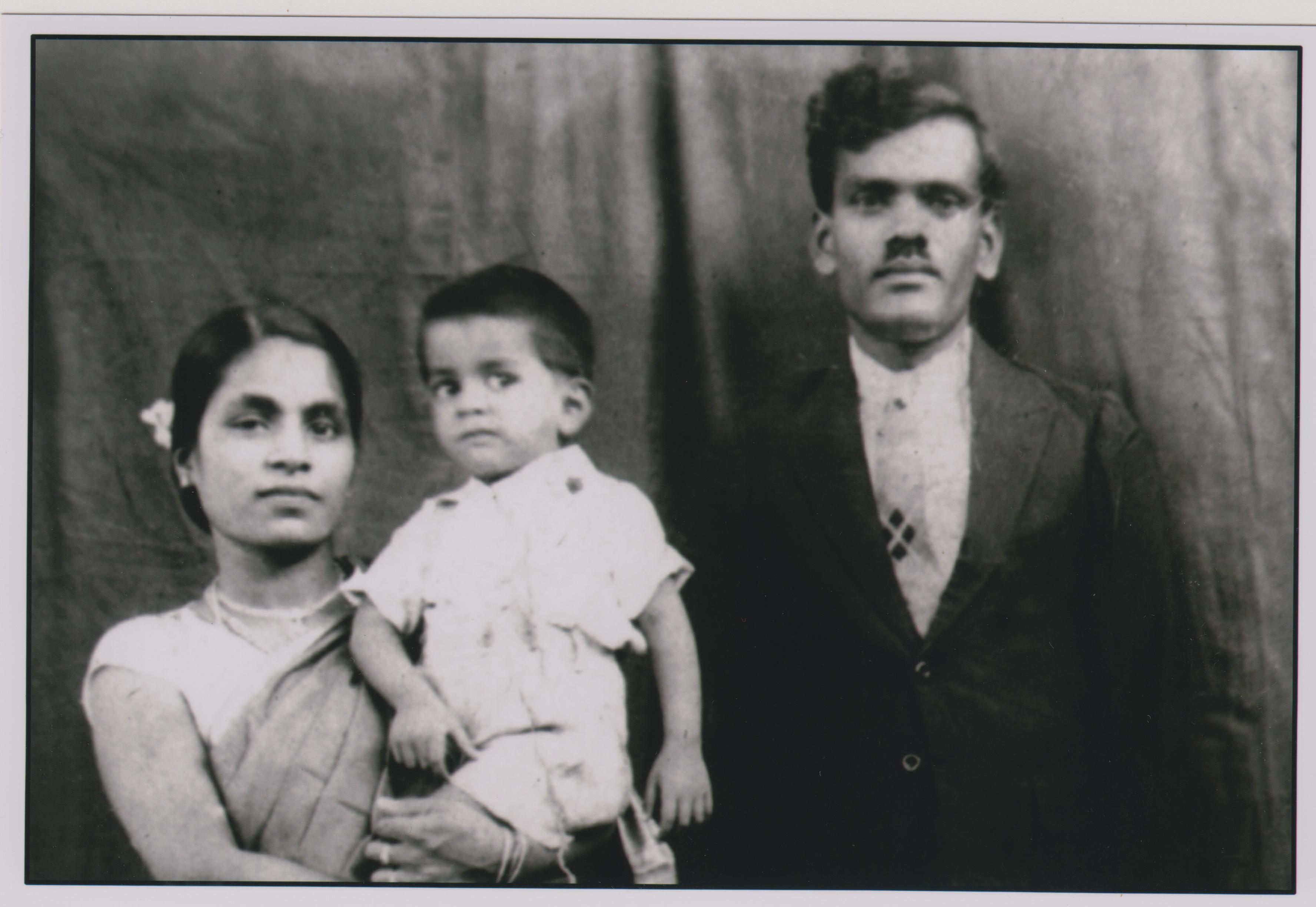

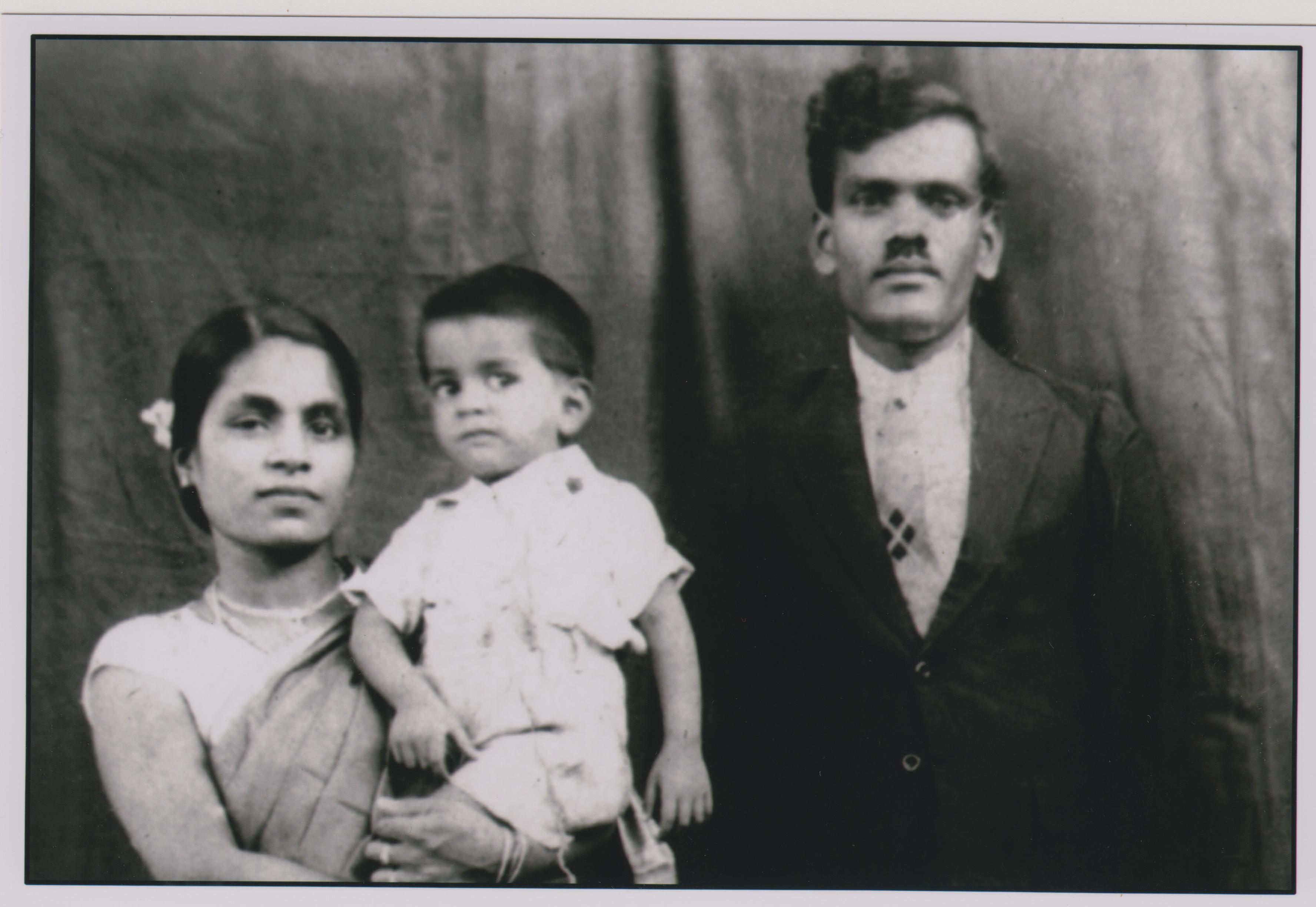

Baskaran with his parents. Photo courtesy: Theodore Baskaran.

So how come a history honours student from Madras Christian College turned into one of India’s quietest, most persistent wildlife defenders?

The Madras Christian College campus, a 400-acre, scrub jungle, supported an amazing diversity of wildlife, including birds, small monitor lizards, jackals and more. Our college had a birdwatching society and I once signed up for a trip to the Vedanthangal Bird Sanctuary that had been organised by Dr. Joshua, our Zoology professor. He introduced me to what he called ‘The Book’ – Salim Ali’s Book of Indian Birds. We had single rooms in our hostel and that facilitated reading, thinking and individualism. History and wildlife? This regimentation of knowledge is very artificial, done for the purpose of studying. Otherwise, everything is interrelated.

Much later, you even taught Film Studies! Will digital media be the ultimate archival tool for generations to come?

After my retirement, I worked as a Director of Roja Muthiah Research Library, Chennai, for three years and this is when I got familiar with digital archiving, particularly Tamil studies. The future of archiving is certainly digital, but there may be questions. For instance, we no longer use so many technologies that were relevant even a few years ago, like the CD. Clearly as technology advances, so will our archiving strategies. But I think many archivists will still swear by microfilm or ordinary film.

The importance of history is neither understood, nor appreciated. What is memory to an individual, history is to mankind. All our chronic problems have their roots in history…

Does today’s generation know enough about our past history and is history really relevant to their lives tomorrow?

The answer to the first question is a definite no. In many colleges, in the last 40 years, history has been discounted. I am connected with some educational institutions and I see that the importance of history is neither understood, nor appreciated. What is memory to an individual, history is to mankind. All our chronic problems have their roots in history… Kashmir, Northeast, even Palestine. Unless one has a good understanding of history, they will swallow propagandist history. Just look at the way the memory of Tipu Sultan has been twisted.

_1613131138.jpg)

Theodore and Thilaka in Kodaikanal. Together, they are a force to reckon with, organising nature camps and trails for hundreds of children. Photo courtesy: Theodore Baskaran.

What about the Bangladesh War of 1972? How were you involved in this?

Earlier, Post and Telegraph was one Department and I was posted as the Vigilance Officer in Shillong, in charge of this combined department. One of its responsibilities during the war was to lay telephone and telegraph cables on the front and I was designated as ‘Officer on Special Duty for War Efforts’ and travelled to the conflict front. I remember once during the Bangladesh War, I was in Agartala having dinner with the Deputy Commissioner (Mr. Lyngdho who later became our Election Commissioner) and we could hear the whining of shells as they flew right above us. “There goes another one,” he would say and continue eating. The short assignment was an interesting period. In Shillong, we had trenches in front of our house. Twice we watched a dog-fight between two aircrafts over the city.

You retired as Chief Postmaster General. How did Government service and conservation meet up?

I look back on my years in civil service with a great sense of satisfaction. I had a lot of freedom. In government service, time is not money! That left people like me time to devote to our interests. Of course, when a new assignment turned up, then for a month or two the schedule got tight. Essentially, with most government jobs, one is left with enough free time to pursue passions. And when Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi introduced the five-day-week, life got even better. The weekends were mine. I was posted to various parts of the country, the Northeast, Gujarat, Bengal… and I got to know both the people and wildlife havens across India.

In 1985, I did a one-year course at the National Defence College and that carried me to Mauritius and the USSR. I also undertook a two-month course in Japan and in 1996 got a United Nations assignment in Kenya, where my wildlife dreams came true! For all this and more, I am grateful to Civil Service for giving me freedom, security and opportunities.

Theodore authored a comprehensive handbook on Indian dog breeds in 2017. Four of Baskaran’s photos of them were released as stamps. Photo courtesy: Theodore Baskaran.

Who were your major influences?

I got to know M. Krishnan after I left college. I asked him what I should do to learn about birds. “Read Douglas Dewar,” he pronounced like an oracle. I was greatly influenced by his ideas on nature, conservation and India. He was an honest man, a rationalist… and had a very sharp mind. He truly did not care for money and status. I loved his writing. He was very good in Tamil too. After I retired, I searched for, found and collected his Tamil articles, most of them written in the 40s and 50s and published as Monsoon and the Call of the Koel. Later, along with friend Rangarajan, I edited about 100 of his English articles compiled into My Native Land. I am also in awe of the writings of nature writer Peter Matthiessen, known for his book The Snow Leopard. Matthiessen developed a style of nature writing that made thousands across the world pause to look at the wild world, with all its life forms and wonders. In Madras in the 1970s, I began to listen to J. Krishnamurthy every winter when he visited the city. His perception of life appealed to me, particularly about nature. In his words: “Can you have a feeling for a tree, look at it, see the beauty of it, listen to the sound it makes? Can you be sensitive to the little plant, a little weed, to that creeper growing up the wall, to the light on the leaves and the many shadows?” In 1997, I attended a four-day retreat in Madras conducted by Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh. That opened new vistas for me. I often go back to his books, particularly Being Peace, which speaks about recovering our own sovereignty.

I wish children today could experience such a life. I remember once rescuing a jungle cat kitten from a well and hand-rearing it. Nature was part of our lives.

You are fortunate to have mind and heart in sync, Theodore. You also played a major role in bringing the public into the wildlife conservation discourse with WWF-India, right?

My connection with WWF began in 1980 when a few of us in Coimbatore started to organise film screenings, exhibitions and lectures. My wife Thilaka and I conducted nature camps for students, under the WWF banner and was eventually nominated as a trustee for two terms. I got to know people like Divyabhanusinh and gained knowledge on conservation from a national perspective.

And the International Primate Protection League?

Yes, while travelling in Mizoram in 1970, I saw a troupe of Hoolock gibbons. I wrote a short note about what I had observed in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. I hardly knew anything about primates, but the note attracted the attention of the International Primate Protection League (IPPL) in North Carolina. They wanted me to be their South Indian Representative. I went on to hold that position for 10 long years. I wrote in the Newsletter of the IPPL about the plight of the lion-tailed macaques and the export of bonnet macaques for laboratory purposes, which had been banned when the late Morarji Desai was India’s Prime Minister.

_1613131803.png)

Theodore has written on several subjects aside from conservation – art, history, films – in both English and Tamil. He harbours a fondness for the latter, as he believes discussions need to be had in the local language to be effective.

Your great passion has been to take conservation to the people in their own language, right?

In Chennai, the estuary of the Adyar river has very productive mud flats that attract thousands of migrant birds, including flamingos, every winter. Twenty years ago, suddenly one day, the estuary was dredged to facilitate boating. Overnight a unique habitat was destroyed. But nobody seemed to notice. That was when I realised that all the discourse on conservation and wildlife was being carried on in English and was missing the real targets. I understood how critical it was for Tamil to be the language of discourse and discussion. This is what motivated me to write in Tamil on issues surrounding nature conservation. In rural areas, people live much closer to wildlife than city dwellers and it is vital for this discussion to be held in their language, in this case… Tamil.

Think of the Save Silent Valley movement. It was successful largely because the entire discourse was in Malayalam. David Crystal, the linguist, said in his book Language Death: “The two-way relation (of languages) to ecology needs to be developed. While discussing ecological issues, languages need to become part of the agenda.” If we want concern about the environment to spread, like literacy, then we must begin from elementary schools, in local languages. All the traditional knowledge of the world is couched in local languages. That is the umbilical cord. The added problem here is that most wildlife biologists are English speaking and largely unfamiliar with local languages and the nomenclatures. I see that as a handicap in their field work.

You were awarded the Iyal Virudhu by the Canada Literary Garden?

This outfit is run by the Tamil diaspora and they choose one Tamil writer for the Iyal award (Iyal means prose). I was given the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014. This is a recognition I greatly cherish because it was given for my nature writing in Tamil. Thilaka and I travelled to Toronto to receive this from the hands of Ms. Radhika, a Tamil MP, in the Parliament of Canada.

What a rich life! You have also lectured overseas, and are very active today. What drives you?

I am interested in what I am doing – wildlife education, Tamil writing – and that provides meaning to my life. I have never once been bored in my entire life.

If you had one piece of advice to give to young India, what might that be?

Look around, and get interested in the external world and all the life forms in it. Your life will be enriched.

Theodore photographed with his family while on safari in Zambia in June 2008. Photo courtesy: Theodore Baskaran.

_1613131138.jpg)

_1613131803.png)