Meet Bivash Pandav

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 10,

October 2020

An eternal optimist and inveterate atheist, Bivash Pandav enjoys working with people and is constantly looking for light at the end of the tunnel. His life has revolved around nature conservation and he says, “as long as I have life in me, I will be working to protect our biosphere. I have immense respect for all religions, but I wish people would go back to the root of all religions, which were inspired by the elements, what we now call the biosphere.” Bittu Sahgal speaks with Bivash Pandav, who has spent a lifetime with the Wildlife Institute of India and who will take over as the new Director of the Bombay Natural History Society on January 1, 2021.

Was it your parents? What sent you on your journey?

My parents are hardworking medical professionals. From them, I imbibed the value of hard work and dedication. Much of my childhood was spent in a small town, Banki, on the bank of the Mahanadi river in Odisha. Wandering along the Mahanadi was what I enjoyed doing most after school hours. I believe the river really shaped who I am today. It keeps me calm and respectful of the magic and the power of nature. The golden sands of Mahanadi, its unpolluted water, scores of migratory waterfowl in winter and its riverine nesting birds in the summer gifted me a childhood of joy and curiosity that I would wish for all children.

At the Sanctuary Wildlife Awards two decades ago, you said you and your wife spent your honeymoon on a moonlit beach watching turtle hatchlings claim their ocean. Is turtle magic still with you?

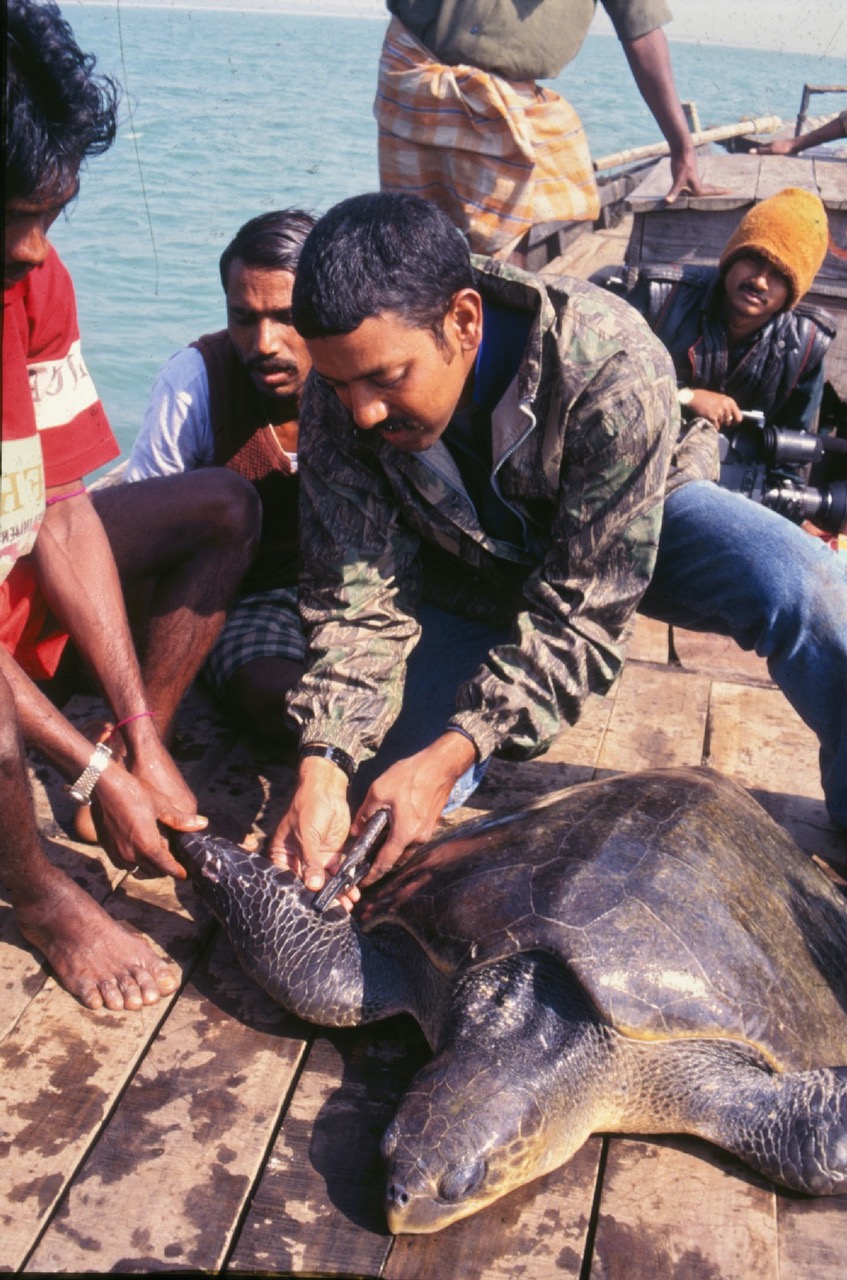

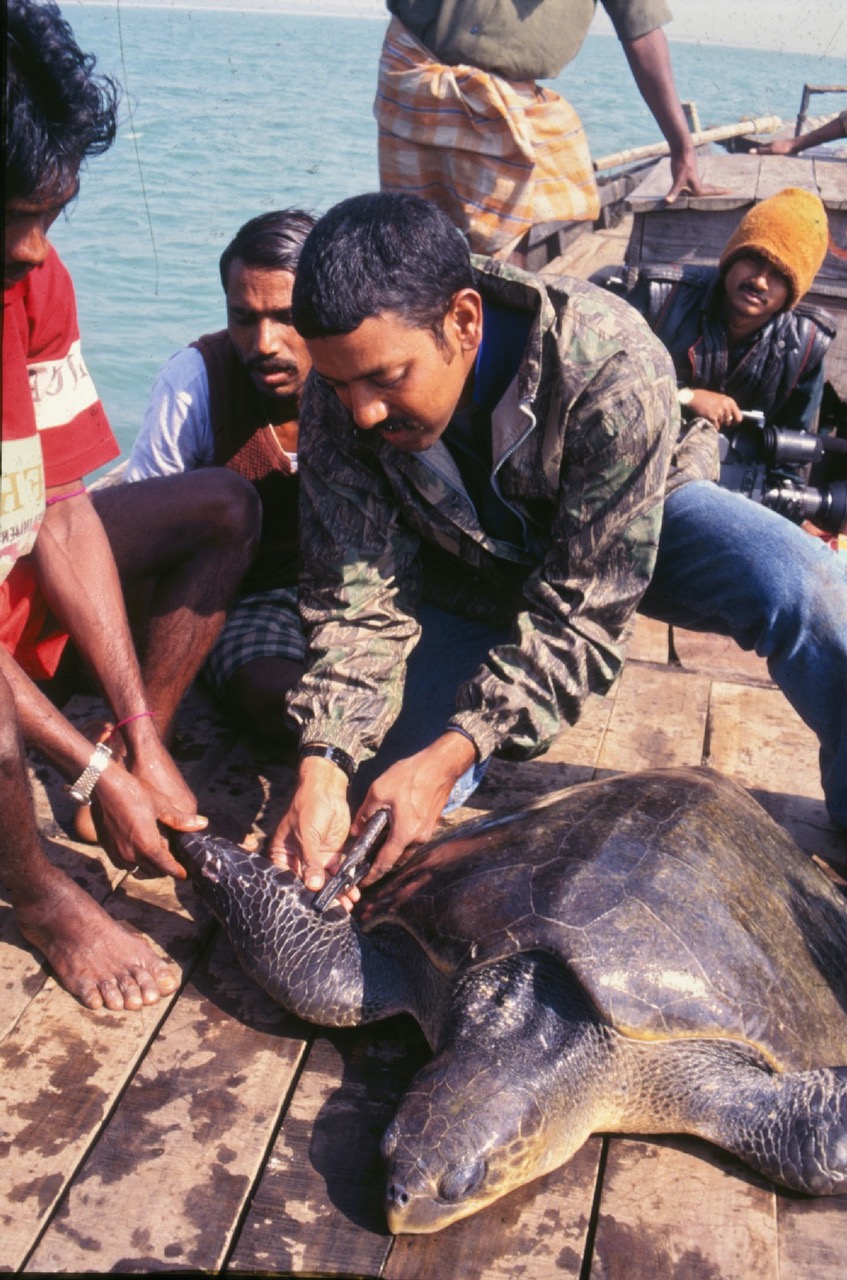

The seven years I spent in Odisha during my sea turtle research between 1993 and 1999 was wonderful, beyond description. Catching turtle mating pairs in the open sea, tagging both male and female turtles to follow their epic journeys across the seas gave me purpose and strength. Watching arribadas of turtles arriving en mass to nest, and then sitting in wonder as millions of tiny little turtle hatchlings emerged 45-60 days later, to return to the sea where some will spend their entire lives, fills you with awe, wonder and respect. I know that most will probably succumb to the trials of life, but that is the way it has been for millions of years. So, to answer your question, yes, I’m still enthralled. I often find myself longing to return to Odisha to relive that life.

Bivash Pandav spent seven years (1993-1999) studying sea turtles, tagging and following their epic journeys across the seas and watching magical arribada spectacles on the beaches of Odisha. Photo courtesy: Ashish Dhir.

Was there a trigger? What guided your trajectory along the path of wildlife protection?

I thought I would be a doctor like my parents. But a pair of Spotted Doves changed the course of my life. One afternoon, in 1988, I noticed a courting pair of doves on the rooftop of our house and wondered what they were. A few months later, I read an article on Dr. Sálim Ali in the Readers Digest, written by its Editor Mohan Sivanand and the late J.C. Daniel of the BNHS. I got to know what ornithology was and the thought struck me that I could well turn ‘watching birds’ into a profession. There was no turning back. Circumstances then conspired to nudge me towards a life of nature conservation. Dr. L. N. Acharjyo, veterinarian at the Nandankanan zoo, introduced me to The Book of Indian Birds and to The Book of Indian Animals. He pointed me towards the Wildlife Institute of India’s masters programme, and went on to help me prepare for the entrance examination. I was selected and joined the programme in July 1991. That has shaped my entire life right to this date.

I have followed your life-journey. You are clearly awestruck by the magic of the biosphere.

Absolutely! The more you experience the natural world, the more it humbles you. When you scale mountains, you feel miniscule. When you dive deep below the sea, you feel vulnerable and small... numbed by the powerful forces of nature. Between curiosity and humility, nature has undoubtedly shaped my world view... shaped who I am.

So why have people like us failed to unite the world to pitch in to protect our biosphere?

Human greed to accumulate wealth and power has blinded Homo sapiens. But we must not forget that when we breathe our last and bid farewell to this world, we will not be departing with even a tithe of what we work all our lives to accumulate. It requires a mind shift away from wealth accumulation as the purpose of life, to the appreciation and gratitude for the miraculous gifts of the biosphere. That mind shift could magically reverse the irreparable damage we are causing to Planet Earth, which is, by nature, self-repairing. Ironically, the physical solutions are relatively easy, as evidenced by the blue skies and cleaner rivers we noticed when the pandemic forced good behaviour upon us all.

Standing on the ridgeline of the Rajaji-Corbett Corridor, a tiger faces the ever-expanding township of Kotdwar that is rapidly encroaching into prime forest habitat. Bivash spent much time monitoring the large mammals of this landscape. Photo courtesy: Bivash Pandav.

Has field biology become too isolated? Has it failed to influence people and policies?

No! Field biology might have taken a backseat, but it is certainly not out of play. It always has and always will play a key role in igniting passion and inspiring both young and old. What Richard Dawkins so poetically describes as “the magic of reality” has the power to rekindle peoples’ interest in nature and the wild. I can and will motivate humankind to savour and protect the natural world.

Your take on Project Tiger?

It still is one of the world’s most successful conservation initiatives, despite some setbacks. But just think. India has over 1.3 billion humans and yet supports the largest population of wild tigers in the world. Do we need any more ratification than that for the project, or for our country’s attitude towards nature for that matter? No one should tamper with a winning formula, particularly since we now know that ecosystem regeneration is going to be critical to tackling our climate crisis and its handmaidens; floods, droughts, famines, human migrations and, never forget, pandemics!

“ When rewilding takes place, true nature conservancy experiences can be offered to people who would much prefer such real wilderness encounters to the crowded, noisy urban-rural hotch-potch that defines wildlife tourism today. ”

So, you have no issue with some select species becoming the biosphere’s brand ambassadors?

Using charismatic animals as flagships and indicator species for larger ecosystem restoration is indeed the way forward. I believe species-specific conservation initiatives implemented on mission mode is destined to be our formula for success in the foreseeable future. But for this, we need not launch a panoply of separate projects for each species. An annual and critical review of the status of critically endangered species like the Great Indian Bustard, hardground barasingha, brow antlered deer, Central Indian wild water buffalo, Bengal Florican, Lesser Florican and gharial should be taken up with the fullest involvement of scientific experts and wildlife managers.

I agree. But will the penny drop in the minds of those driving our destinies today?

It will. The key is to convincingly underscore the fact that ecosystems are infrastructures in their own rights and that ensuring ecological harmony for species and habitats is probably our best developmental option in the years ahead, particularly when multiple threats are being thrown at us that we have no way of countering without the ecological services rendered by plants and animals. Of course, we have to prioritise extra protection for some species that are in dire straits. More funds and other resources will need to be allocated. Political will is required and this must be motivated. The participation of planners, local experts and communities may need to be won. If we fail, the desire to achieve conservation will probably remain mere conversations.

Bivash Pandav at the Chilla–Motichur wildlife corridor of the Rajaji National Park in Uttarakhand. Photo courtesy: Jayjit Das.

Is India’s planning process out of sync with the impending threats the planet faces?

All change is gradual. We must keep our focus steady. Whatever else we do, we must reach out to planners and policy makers. We may often criticise them for their ideas and their focus on development issues. But mere criticism will not be of much help. I believe we must keep connections strong with “the system” and seek to change it from within. There is absolutely no point in running away from the system and crying hoarse all the time. There is no more effective way to win support from the system than to inculcate genuine understanding and love for nature in key decision makers, ideally at the earliest stage of their careers. A sensitised decision maker will ward off problems before they turn into skirmishes, legal battles or worse. While we can and must sensitise public opinion and invest in winning support from large numbers of people, we must always create links of trust with decision makers. If the above steps are taken, things will undoubtedly change for the better.

Has ethology lost out to morphology? Has science missed a chance to nudge humanity towards a safer course, because it focused on measuring instead of understanding?

Science down the years has evolved. I don’t think we are still stuck with the morphology fixation that once defined most science. I also think that from time immemorial the study of animal behaviour, or ethology, has greatly enhanced our understanding of the natural world. Think of Charles Darwin... he studied animal behaviour and his conclusions impacted the world, or consider the earliest practitioners of Ayurveda. Conservation biology has grown in leaps and bounds down the decades. India has a fantastic pool of conservation biologists who have helped us understand our natural world better. What we are collectively working towards is greater synergy between field biologists and Protected Area managers.

Marine turtles off the coast of Odisha, Sri Lanka and heaven knows where else... what drew you to turn to tigers and elephants?

Life thus far has been a wonderful journey for me. ‘When in Rome, do as Romans do’, I always say. I learned about and adapted to whichever habitats and species I was privileged enough to study. Moving to tigers and elephants from marine turtles was as natural as breathing. These diverse species and ecosystems opened my life to the diversity around us and helped me find my place in it.

Working in the Rajaji-Corbett landscape for the past 15 years, says Bivash, has truly been a rewarding experience. Jim Corbett often described man-eaters that were incapacitated by porcupine quills. This camera trap image from the Mandal Range, Kalagarh Division, in Corbett Tiger Reserve captures a tiger considering the risks of going after the porcupine. Photo courtesy: Bivash Pandav.

You were with WWF-International too right?

Yes, I had an enriching four-year stint with WWF-International between 2007 and 2010. I was based as an out-posted staff in Kathmandu and coordinated WWF’s tiger programme in 11 tiger range countries. This allowed me the opportunity to walk and work in almost all tiger range countries. It was a treasured experience. And the story continues!

Do you get frustrated by the lack of unity between organisations set up to achieve the same goal ... protecting the biosphere?

A little. Sadly, the lack of unity is palpable. Perhaps we have veered too far towards corporate-style professionalism, instead of using science, passion and the visceral urge to protect wild nature. But unity can and will be built. Nothing is impossible. Attitudes need to change. Bridges need to be built. We will achieve all this and more.

“ The more you experience the natural world, the more it humbles you. When you scale mountains, you feel miniscule. When you dive deep below the sea, you feel vulnerable and small... numbed by the powerful forces of nature. Between curiosity and humility, nature has undoubtedly shaped my world view... shaped who I am. ”

How can we make local communities living closest to our biodiversity the primary beneficiaries of a biodiversity comeback?

We don’t have to over-think this. Look at Nepal. Despite abject poverty and years of civil unrest, Nepal has achieved tremendous conservation success only because of the involvement of local communities in letter and spirit. The community forest programme and the buffer zone management programmes being carried out by the Nepalese government are worth emulating.

People have tried, but you believe this can still be achieved in India?

Give people what they deserve. Make them the primary beneficiaries of biodiversity renewal. Don’t throw scraps at them. People residing in the vicinity of PAs should be the rightful beneficiary of revenue generated through tourism, not just the rich resort owners who dole out a few jobs here and there. Wildlife tourism needs an overhaul in India. The way wildlife tourism has unfolded in our Protected Areas (PAs) today is not sustainable. The mushrooming of hotels and resorts around our PAs need recalibration. Both land owners and landless residents must have a real stake in restoring ecosystems outside our PAs. Right now, they are victims of local overabundance of wild animals that raid their crops, or lift their livestock. If, as was done in Maharashtra, villagers are encouraged to aggregate their land and, while retaining ownership of their lands, they are able to collaborate with tourism professionals to create and manage homestays, they will be more financially secure, wildlife will have more space, ecosystem regeneration will help sequester and store carbon and aquifers will be better stocked with life-giving water. This does not even begin to describe the benefits that can accrue to communities and to national development. On these public lands, when rewilding takes place, true nature conservancy experiences can be offered to people who would much prefer such real wilderness encounters to the crowded, noisy urban-rural hotch-potch that defines wildlife tourism today.

If you had a magic wand, what would you change about the behaviour of Homo sapiens?

I don’t believe in magic wands, but if equitable justice to both local communities and wild species is achieved as suggested above, I believe a whole new chapter can be written on the relationship between humans and wildernesses. Empathy. Love. Respect. Gratitude. Awe. Curiosity. These are just some of the ingredients that might trigger behaviour change in humans, even more effectively than an imaginary magic wand.