Can Fibreglass Save the Hornbill?

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 22

No. 2,

February 2002

By M.K.S. Pasha and Vidya Deshpande

This February, the ‘Nyokum’ festival of the Nishi tribals will be celebrated with all the traditional pomp and accompanying regalia. The Nishis wear the Great Indian Hornbill’s beak as part of their headgear, known as bopa, to symbolise their manhood. But this time around, the beaks will be fibreglass replicas instead of the real ones. Members of the Nishi tribe have switched over to these replicas with the help of the Arunachal Wildlife and Nature Foundation (AWNF) and Wildlife Trust of India (WTI).

This move could be a great leap forward for the conservation of hornbills, which are especially vulnerable in northeast India due to the traditional value attached to their feathers, casques, fat and flesh among many tribal groups. Hunting pressure has caused the local extinction of the Great Indian Hornbill in many areas in eastern and central Arunachal Pradesh.

India is home to nine species of hornbills and the northeastern region has the highest diversity of hornbill species in the country, with five hornbill species found here. Three of these are endemic to the region: the Wreathed Hornbill Aceros undulatus, Brown Hornbill Anorrhinus austeni and Rufous-necked Hornbill Aceros nipalensis. The other two species, the Great Indian Hornbill Buceros bicornis and the Oriental Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros albirostris also occur in other parts of India. Barring the Oriental Pied Hornbill, all the others are listed under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. The Rufous-necked Hornbill is listed as ‘rare’ in the IUCN Red Data Book (1990).

Great Indian Hornbill. Photo: M.K.S. Pasha / WTI

Entirely dependent on forest habitat and a key seed disperser, the hornbill is critical to forest survival and restoration. The birds primarily consume Ficus fruit, with small amounts of oily fruit and animal prey. Hornbills have unique nesting habits. The nest site is a natural cavity in a large diameter tree, extending above the forest canopy. Such sites are rare and thus act as a limit to the growth of hornbill populations, even in pristine forests. In areas that have been logged, the birds may continue to survive for years, but without reproducing.

The Great Indian Hornbill (state bird of Arunachal) is the most coveted by tribal groups, followed by the Rufous-necked. Great Indian Hornbills inhabit the canopy of tall evergreen forests from sea level to 2,000 m. elevation. There are no current figures for population size, but estimates of population density of two to four per 100 sq. km. of non-degraded habitat have been made. There has been no accurate measurement of their remaining habitat yet. However, the disappearance of tropical forests throughout the species’ range is incontrovertible and no doubt is playing a key role in the continuing decline of populations.

The Nishis use the upper beak of the casque as part of their ceremonial headgear, while the Wanchos adorn themselves with the tail feathers of the Great Indian Hornbill. Tribal women often wear the feathers of the Oriental Pied Hornbill in their ears.

Hornbill feathers are a matter of prestige and not everyone can possess them. Among the Wanchos, only the chieftain and other important people in the hierarchy are deemed worthy enough to adorn themselves with the feathers. At current market prices, two body feathers can be purchased for Rs. 260, while a single tail feather can cost up to Rs. 700. Apart from the ornamental value, hornbills are also killed for their meat. Some tribal groups use the fat for medicinal purposes and the Mishmi women are allowed to eat only rat and hornbill meat.

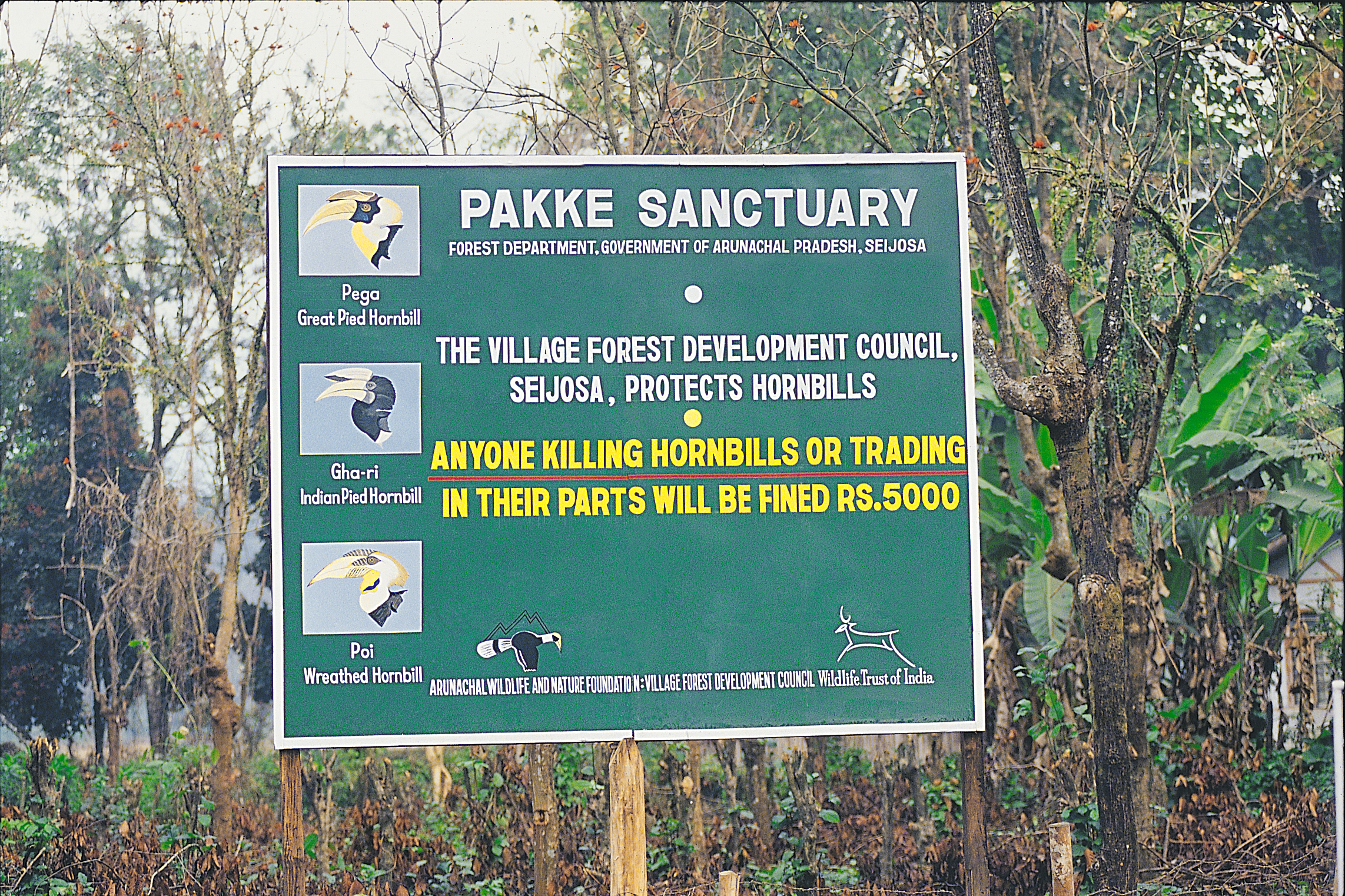

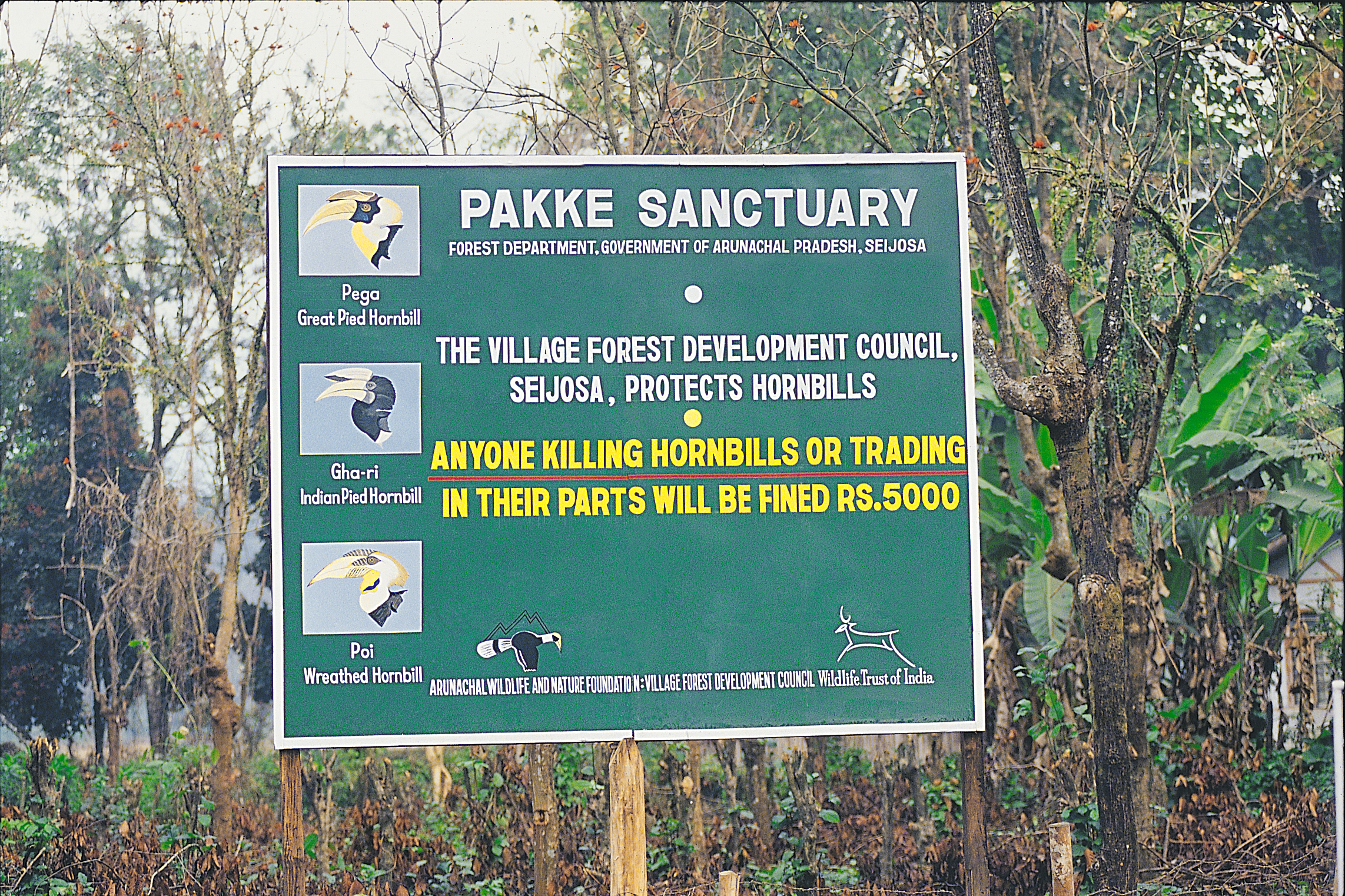

The Pakhui Wildlife Sanctuary is home to a considerable hornbill population. Local villagers have now decided to impose fines on anyone caught poaching the birds. Photo: Gautam Chatterjee.

Local NGO AWNF came up with the ingenious idea of giving the Nishi tribals fibreglass beaks that resembled the genuine article in order to wean the Nishis away from hunting hornbills. AWNF member and a Nishi himself, Tadab Nabum campaigned actively with his tribesmen to give up this tradition. “Initially we faced stiff opposition from the tribe members, as they felt their traditions were being undermined,” Tadab says. “But we made the elders realise that unless the killing of hornbills stopped, the Nishi would live with the stigma of being the only tribe in the world to have wiped out an entire species from the face of the earth,” he says. His efforts finally paid off when the Nishi community publicly asserted that the loss of hornbills would be a threat to their culture and tradition, of which the bird was an integral part.

Many of the Nishi people are happy that an alternative to the real hornbill beak is now available. “Ever since killing hornbills has become a punishable offence, we were upset that our tradition would die. But the fibreglass alternative allows the tradition to continue,” said one of the community members.

Most of the hornbill hunting takes place inside the Pakhui Wildlife Sanctuary, located in East Kameng district, a hornbill stronghold. Together with the WTI, local villagers have granted the Village Forest Development Council the power to impose a fine of Rs. 5,000 on anyone caught hunting hornbills in Pakhui.

The switch to artificial beaks, together with other conservation initiatives, now gives the hornbills a better chance of survival.

Tadab Nabum with a fibreglass ‘hornbill’ beak. The casque and feathers of the Great Indian Hornbill are prized by many tribal groups in the northeast. Photo: Gautam Chatterjee.

Tadab Nabum with a fibreglass ‘hornbill’ beak. The casque and feathers of the Great Indian Hornbill are prized by many tribal groups in the northeast. Photo: Gautam Chatterjee.

Pakhui’s Divisional Conservator of Forests, C. Loma, along with Tadab Nabum, of the Arunachal Nature and Wildlife Foundation, both

Nishis, worked hard to convince the tribe to switch over to fibreglass beaks instead of real ones.

Why do the Nishi people wear the hornbill beak as part of their headgear?

Among the

Nishi, only the priest or headman used to wear the hornbill beak to symbolise authority. Over time, all the

Nishi men started wearing the beak as a symbol of their manhood. Wearing the beak meant that the wearer had killed the hornbill himself, a sign of valour and bravery.

How did you convince the tribals to stop hunting the hornbill?

I met and convinced Tadab Nabum, a tribal hunter to give up hunting and work for wildlife conservation instead. He started the Arunachal Nature and Wildlife Foundation and came up with the idea of fibreglass beaks. Convincing the tribals then became easy as Tadab took the lead in talking to his own people. He told the tribals that if the hunting continued, a time would soon come when the birds would vanish, and with it, the tradition of wearing the beaks.

Has the replica been accepted?

The replica looks just like the original. The original beaks tend to lose their colour after about six months and are prone to insect attacks. But the fibreglass beaks do not lose their original colouring and are immune to insects. This made it easy to convince the people.

Who were the people instrumental in promoting this idea?

The late Arunachal Minister for Education Dera Nathung helped, as did 60 MLAs in the state assembly, 15 of whom are

Nishis.

How many people have adapted to the change?

So far, we have given away 96 fibreglass beaks and the demand for more is on the rise. Another 100 will be distributed this month. Right now, the beaks are being supplied free-of-cost by the Wildlife Trust of India, but we plan to charge a token price, using the money for beak production. This way, the programme can become self-sustainable.

What is being done to stop other tribals from hunting the hornbill for meat?

The

Nishis have already accepted the ban on hunting hornbills. The Seijosa Village Development Council has also imposed a fine on the hunting of hornbills. Most other tribal groups, especially the

Wanchos,

Mishmis and

Nocte, who eat hornbill meat, have begun to respect the ban. Last season, we conducted a hornbill census in Pakhui and found that with these measures in place, the hornbill population has gone up to 1,000 birds of all five species, compared with a couple of hundred earlier.